I spend a lot of time in the archives of literary magazines. There’s something tenuous and beautiful about these often shoestring, sometimes short-lived, always ambitious publications. If you want to understand the contours of American literature for the past 100 years, there is no better place to watch the evolution of writers than in these magazines, where future legends begin their careers with one-line biographical notes.

I wrote my new book, The Habit of Poetry: The Literary Lives of Nuns in Mid-century America, because I kept on coming across poems by nuns in these magazine archives. Some of the poems were devotional and traditional. I say that without disdain; these women wrote with measured skill. Yet more often than not, the poems were stylistic, satirical, and subversive.

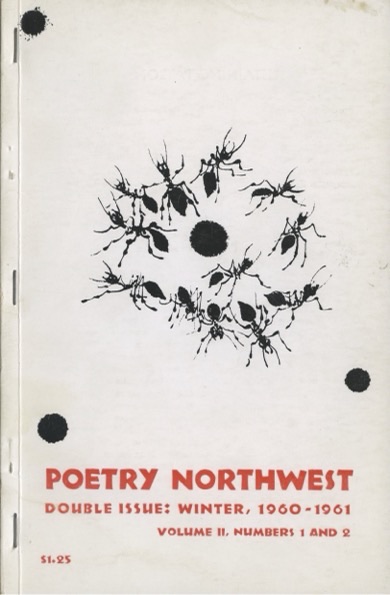

One day, during my archival research, I came across the Winter 1960-61 issue of the quarterly literary magazine Poetry Northwest. Ants huddle in the center of the magazine’s cover, which is a reproduction of the painting “Ant War,” by Oregon-born artist Morris Graves. Although the magazine was based in Seattle, its writers hailed from across the country. Founded the previous year, the magazine had already published Anne Sexton, Stanley Kunitz, and Philip Larkin. In this issue alone, luminaries like William Stafford, Donald Hall, Thom Gunn, and Philip Levine published alongside lesser-known writers like Allyn Wood and Sister Mary Gilbert, a Sister of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary.

The issue featured three poems by Gilbert, born Madeline DeFrees, who taught at Holy Names College in Spokane. The editors called her “one of a lively and generously gifted group of young Catholic poets.” “Tumbleweed” ponders the “mobile American par excellence,” and appreciates how “rootlessness” is “its survival.” In “A Kind of Resurrection,” Gilbert deftly paces single-sentence stanzas. And the strongest poem of the trio, “Nuns in the Quarterlies,” paints a revealing portrait of mid-century nun-poets.

Gilbert begins by documenting how nuns often appear in art: “Used as accents in a landscape or seaview, upright in merciful black on the sand’s monotone, / not even the devil’s advocate could question their purely decorative purpose.” These nuns are calming; “they are all suggestion, posing no problem deeper than the eye.”

Elsewhere in culture, nuns are depicted in more unusual ways, in the “slicker pages of the thicker magazines / where nuns drift in and out of nightmare scenes.” They perfectly encapsulate female archetypes: “Women, the ancient lie, the unattainable mystery, / the apple high on paradisal branches, / the history of heaven and hell, of fall and pardon; / innocence unmasked in God’s own Garden.” Gilbert ends with an affirmation: “Nuns are the fictions / by whom we verify the usual contradictions.”

The poem is light but not loose; perceptive but not taciturn. Its points are well taken, and yet it seems composed with a wink. Sister Mary Gilbert was a nun, and she was in the quarterlies. Her poem catalogs stereotypical presentations of nuns, but doesn’t address the nuanced skill of her own work: the poetry of a nun. She wasn’t alone: in mid-twentieth-century America, nuns were publishing widely in the finest literary publications. Something, it seems, was happening—and it is time we understand why the nuns of this era were drawn to writing and publishing poetry. Perhaps among these pages nuns could be their most artistic and authentic selves; their measured and skilled lines certainly suggest literary and personal ambitions that can help illuminate the religious lives of women of their time.

Another notable example is the poetry of Sister Maura Eichner. Born Catherine Alice Eichner in Brooklyn on May 5, 1915, her childhood was marked by tragedy. Her mother died when Eichner was less than a year old. Her father soon remarried, but his wife deemed young Catherine “a terrible little thing,” and sent her to live with extended family in a railroad flat. “I was always a little startled, then beguiled, by the sound of my Irish grandfather’s voice,” she recalled. “The brogue was rich and the inversions magical. Like so many children in the New York city school that I attended, I had a German grandfather who sang Bavarian songs to me.” The various ethnic traditions of her family were a direct example of how language hewed close to culture, and how storytelling could be lifted by intonation and style.

At 17, she worked as a secretary for the future founder and first president of the American College of Nurse-Midwives, Hattie Hemschemeyer, at the Lobenstine Midwifery Clinic, which supported pregnant women and midwives. In 1933, she entered the order of the School Sisters of Notre Dame. After teaching younger students at St. Mary Academy in Annapolis and Notre Dame Preparatory School (“It was impossible,” she wrote. “It was wonderful.”), Eichner joined the English faculty at the College of Notre Dame of Maryland in 1943, and remained there for the next 50 years. By all accounts, she was a uniquely generous and skilled teacher, an inspiration for her students.

She was also a gifted poet. Eichner was credited as simply “Sister Maura” in the Summer 1966 issue of The Literary Review, in a special section titled “Poems by Priests and Religious.” She appeared alongside priests, seminarians, and other nuns. Thomas Kretz, a Jesuit novitiate, curated the section. Rather than residing in “ivory towers,” he said, the religious poets collected here were “vitally concerned with the wrap of flesh and does not try to prescind from it.”

Eichner’s sequence of five poems was titled “Suite: University Campus.” The poems are skilled, playful, and pleasantly odd. In the densely packed “Parking Lot,” “dilapidated cars roar” spewing a “private hell mouth of / sound and smoke.” Among them, “four late butterflies detour // over macadam as meadowland”—few could turn a phrase about asphalt with as much song. A “fierce” cat “nurses her brood / in a leaf-logged drain where no one would / park though anyone could.” Her imagery is as rich as her rhythm: “Dusk. A hidden switch: fluorescent rings // of night-blooming aureoles take the parking lot, / islands, oaks, hop-scotch squares.”

The next poem in the sequence considers the South African novelist Alan Paton, whose “words have no suasive / Disneyland rhumba” nor “mock-modest statement.” He eschews “cinemascope documentary” instead opting to “speak only of this moment’s / harrowing of hell.” Despite their different subject matter, the poems are syntactic mirrors: truncated narratives in which phrases are stitched by semicolons and colons, appended with terse, single-word sentences. The mode perfectly fits her poem “Advertising,” truly a work of its era: “On the neuter-gender sheath / paint Campbell soup pop art; / blow up breasts and rump / to flip the leering heart.” Next: grow out “the beatle hair,” don black boots: “shadow the eye; / pluck the eyebrow, tilt the head. / Sell it for cool and high.”

In her work elsewhere, Eichner pivoted from play to profundity. In “Mythopoesis,” she channels the cadence of newspaper reports to reveal the inadequacy of how we describe and respond to loss. The poem documents the crash landing of United Airlines Flight 859 on July 11, 1961. Started by hydraulic failure while in flight, the plane was thought to have landed safely in Denver, before bursting into flames. Eichner captures the eerie, ephemeral calm in her first stanza: “the passengers touched the buckles / of seat belts, and glanced at their traveltight mouths in the window.” Their mirror images disappear in the smoke. Eichner details the destruction, interspersing “strophe” and “epode” into the text, imbuing the crash with cathartic results: “The nation sipped morning coffee with disaster.”

Her more stylistic work is no less Catholic than her devotional verse. “When the poet looks at reality,” Eichner wrote, “the mystery within it demands reverence and communication.” Eichner and her fellow nun and sister poets retreated from the wider, bustling world—and sometimes retreated from the communities of their convents and institutions—to discover the song of poetry. Their inspirations varied, and their styles differed, yet they shared a deep concern for the place of an individual woman within a larger order. The legacy of these mid-century nun and sister poets is notable: that in an increasingly secular world, skilled and inspired work from religious poets can still shine, even as those poets wrestle with their identities and faith.