Claire,

I called this morning to tell you I wanted to talk to you about something, but that I needed to put my thoughts down in writing. Organize them. So here they are.

You know I’m trying to find out who sent the anonymous postcard to Lélia, and obviously, this whole investigation has stirred up a lot of things inside me. I’ve been reading a lot of books and I stumbled across this quote from Daniel Mendelsohn in The Elusive Embrace: “Like a lot of atheists, I compensate by being superstitious, and I believe in the power of first names.”

The power of first names. That little phrase did something funny to me. It made me think.

I’ve realized that, when we were born, Mom and dad gave us both Hebrew first names as middle names. Hidden first names. I’m Myriam and you’re Noémie. We’re the Berest sisters, but on the inside, we’re also the Rabinowitz sisters. I’m the one who survives, and you’re the one who doesn’t. I’m the one who escapes. You’re the one who is killed. I don’t know which is the heavier burden to bear, and I wouldn’t dare to guess. It’s a lose-lose situation, this inheritance of ours. Did our parents even think about that? It was a different time, as they say.

Anyway, Mendelsohn’s words shook me up. And I’m wondering what I—you—we should do with these names. I mean…I’m wondering what we’ve done with them so far, and I’m wondering how they’ve affected us, silently, invisibly. Affected our personalities and how we look at the world. Basically, to go back to Mendelsohn again, what power have those first names had in our lives? And in our relationship as sisters? I’m wondering what conclusions we can draw, and what we can make of this whole first-name business. First names that showed up out of the blue on the postcard, as if they were being thrown in our faces. First names hidden in our family names.

The effects, for better or worse, on our temperaments.

Those Hebraic-sounding first names are like a skin beneath the skin. The skin of a story bigger than us, that came beforeus and goes far beyond us. I can see, now, how they instilled something disturbing in us. The idea of fate.

Maybe our parents shouldn’t have given us such heavy first names to carry. Maybe. Maybe things would have been easier, lighter inside us, lighter between us, if we weren’t Myriam and Noémie. But maybe they would have been less interesting, too. Maybe we wouldn’t have become writers. Who knows.

Recently I’ve been asking myself: how am I Myriam? In what ways am I Myriam?

Here are the answers I’ve come up with.

I am Myriam in that I’m the one who’s always escaping. Who never stays at the table after dinner. Who’s always leaving, going somewhere else, feeling like I have to save myself.

I am Myriam in that I can adapt to all kinds of situations. I know how to blend in, to lay low. I know how to contort myself to fit into a trunk; I know how to become invisible; I know how to change my environment, change my social milieu, change myself.

I am Myriam in that I know how to seem more French than any Frenchwoman. I anticipate situations, I adapt, I can blend into the wallpaper so that no one wonders where I’m from. I’m discreet, I’m polite, I’m well brought up. I’m a bit distant, and a bit cold, too. I’ve been criticized for that a lot. But it’s what has allowed me to survive.

I am Myriam in that I am tough. I don’t show tenderness even to the people I love. I’m not always comfortable with shows of affection. Family, for me, is a complicated subject.

I am Myriam in that I always know where the exit is. I run away from danger. I don’t like dodgy situations, and I see problems coming long before they actually happen. I take the side streets; I pay attention to how people act. I prefer still waters and I always slip through the net. Because I was chosen to be that way.

I am Myriam. I’m the one who survives.

You are Noémie.

You are Noémie even more than I am Myriam.

Because in your case, the first name wasn’t even hidden.

We used to call you Claire-Noémie sometimes, like a hyphenated first name.

I remember, when we were little—you must have been five or six, and I was eight or nine at most—one night you called tome from the other side of the bedroom. I came over to you in your little bed, and you said:

“I am the reincarnation of Noémie.”

How very strange that was, when you think about it. Wasn’t it? Where on earth did that idea come from? You were so tiny! Lélia never talked to us about her past or her family history back then.

We never spoke about that night again, and I don’t even know if you remember it. Do you?

Anyway, those are my thoughts.

I don’t know what I’m going to find out from my investigation, or who wrote the postcard. And I don’t know what the consequences of all this will be. We’ll see.

Don’t worry about writing me back right away; there’s no hurry. I’d imagine you’re almost finished correcting your proofs. ‘Proofs’—that is definitely the right word for them. Good luck with it. I can’t wait to read your book on Frida Kahlo; I just know it’s going to be beautiful and powerful and huge for your career.

Big hugs to you and Frida too,

A.

*

Anne,

I’ve read your e-mail half a dozen times since you sent it. I’ll admit it—the first two times both made me cry. The way you cry when you’re a kid and you’ve hurt yourself. Uncontrollably, and loudly, hiccupping and shaking. Probably because you think your pain is unfair somehow.

But then, the third time I read it, I didn’t cry. And then I read it again and again, and I was able to…sort of neutralize my initial reaction, which was denial, and a kind of fear. Dread, maybe.

And that allowed me to focus on your questions. So now I’m going to try to answer them.

Yes, I remember.

I remember calling to you one night when I was really little, to tell you I was the reincarnation of Noémie. It’s one of my few early-childhood memories, and I remember it as clearly and vividly as if were a movie scene playing in my head.

Yes, it’s true that Lélia didn’t actually talk about all that stuff back then, but she communicated it in other ways. It was everywhere. In all the books in the study, and in her pain, andthe things she said and did that didn’t quite make sense, and the ‘secret’ photos that weren’t very well hidden at all. TheHolocaust was like a treasure hunt in our house. You just followed the clues.

Isabel didn’t have a middle name. Neither did Lélia. Yours was Myriam. And mine was Noémie.

Mom told me once that she originally wanted Noémie to be my first name, but Dad suggested that it would be better as my middle name. “But Noémie is so pretty as a first name too,” Mom said to me. And it is.

Then she said, “But ‘Claire’ was a good choice. It means ‘light’. And I think that’s really lovely too.”

This, coming from Mom, whose name in Hebrew means ‘night’.

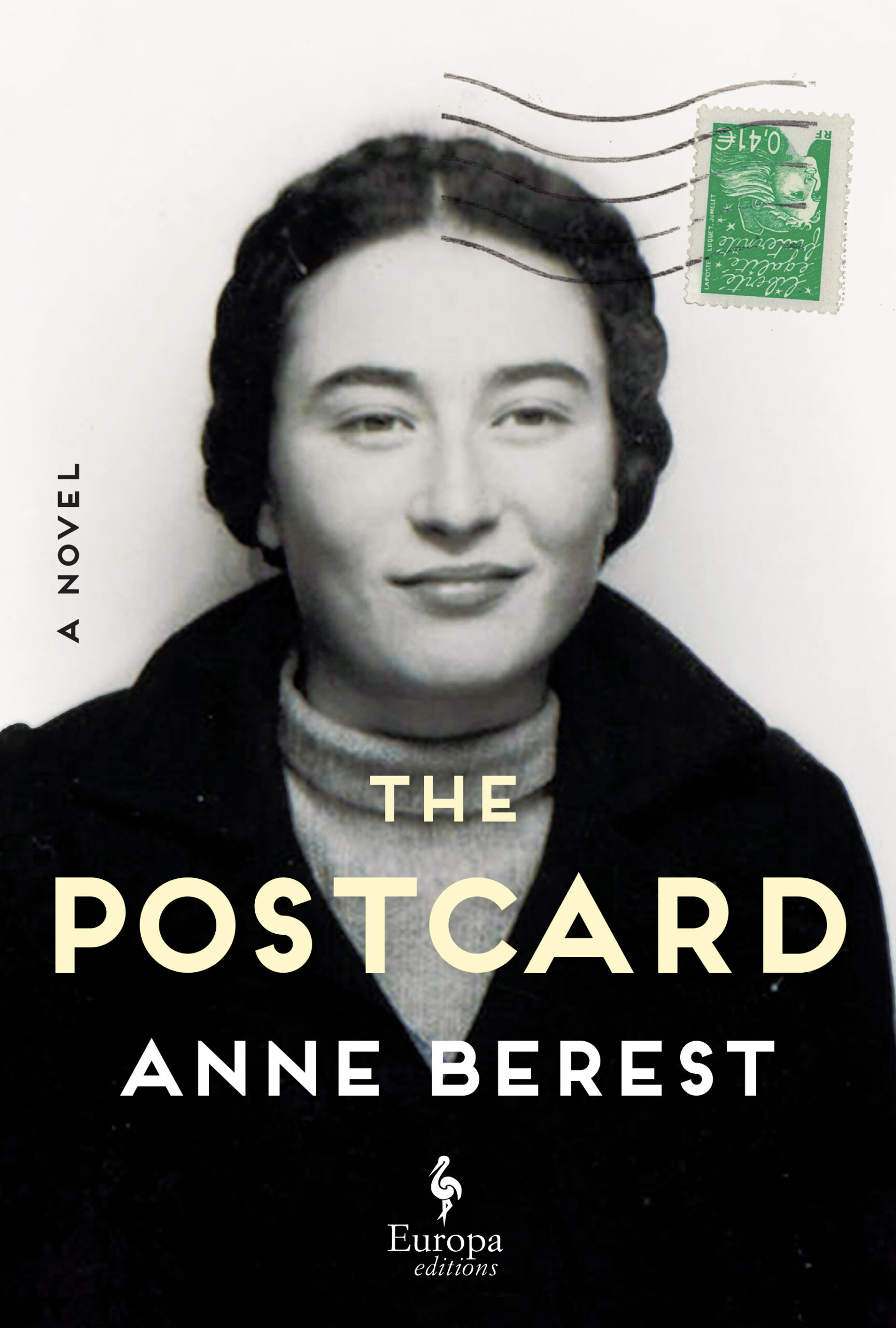

When I was little, I used to look at the photo of Noémie Rabinowitz I’d swiped from Mom’s desk, to envisage a truth. En-visage, in the literal sense. I wanted to look into this dead girl’s face—her visage—to see if there was anything of myself in it. Iremember realizing that we had the same cheeks (I’d say cheekbones now, of course, but I didn’t really understand the conceptof cheekbones when I was that young). We had the same blue eyes.

Whereas yours are green. Like Myriam’s.

I had the same long braids.

But did I braid my hair that way for ten years because I was imitating Noémie? That’s the question. I’m not really looking for an answer.

In Mom’s photo, Noémie looked almost Mongolian, with her slightly slanted eyes and those famous high cheekbones. My eyes almost disappeared when I smiled in pictures, narrowing to slits, and people would have seen our Mongolian ancestryin my face, too. And let’s not forget the Mongolian birthmarks. They show up on a baby’s buttocks at birth and then they disappear, apparently. Remember how Mom used to talk about how we all had them? Of course, as I’m writing this e-mail, my thirty-eight-year-old self is blurring together with my six-year-old self, and I’m writing to you from that perspective. All mixed up and confused.

For reasons I didn’t really understand, I became a passionate volunteer for the Red Cross, at the exact age Noémie was when she found herself working in the infirmary at her transit camp before being sent to Auschwitz. I was spending every single weekend at the Red Cross—and then all of a sudden, overnight, I just stopped going.

I used to wonder about all kinds of strange things at night when I couldn’t sleep.

I remember with cruel clarity the day when someone said to me—I was still only little—“Your family died in an oven.” For a long time after that I used to look at the oven in our kitchen and try to figure out how that was possible. How had they managed to cram everyone in there? It’s the kind of mental gymnastics that leaves you exhausted. When I was a teenager, during a party I threw impulsively when our parents were away, I broke that fucking oven, and I remember how it made me feel strangely better. Relieved.

When I ditched everything and ran off to New York on a whim at the age of twenty, I went to the Holocaust Museum. So many rooms. And in one of those rooms, on a wall, a photograph. Tiny. It was Myriam. I recognized her. I started to feel sick. I went closer and looked and there was a caption: Myriam and Jacques Rabinowitz, from the Klarsfeld Collection.

I fainted. They took me out of the museum through an emergency exit. I remember that.

But yes. When I was six, I did call you over to tell you that thing. Monstrous, in a way. That I was the reincarnation of that dead girl, who I didn’t know, who no one knew, because she died too soon, and the people who knew her died with her. All of them, all at once. And because she didn’t survive. And I don’t know anything about her. And it’s horrible.

But I know—we know—that she wanted to be a writer.

And so, when I was little, I said I would be a writer. And I stuck to it, with persistence and endurance, until I became one for real.

For real, as little kids say.

And yes, during my wild days, sometimes I felt like I was living the life that another girl didn’t have the chance to live, because it was my duty. I don’t feel that way anymore, though. But I would say it in my mind when I felt bad about myself, like an exorcism. And here we are.

I’m the one who played leapfrog with her fears, jumping over them to see how far I could get. And the one who got tattoos all over her arms, to cover up the shadows.

But I’m willing to admit that in an e-mail now, because I have nothing to be ashamed of. I’m not ashamed anymore. Not ashamed of my arms, I mean.

So yes, in that way, you are Myriam. You’re discreet, you’re polite, you’re well brought up. You’re the one who always knows where the exit is, and you run away from danger, and dodgy situations. The opposite of me. Who’s gotten myself into all kinds of dodgy and dangerous situations—to say the least.

Myriam saves herself, and everyone in the story dies.

She didn’t save any of them.

But how could she have?

I’ve asked you to save me. So many times. What a burden I’ve been on you.

When I was six and I told you I was the reincarnation of Noémie. When I told you I loved you, and said I didn’t understand why you never said it to me, or hugged me (another incredibly vivid early-childhood memory). Because, as you say, you or Myriam, you seem tough and cold. You have trouble expressing your feelings. It makes you uncomfortable.

And I’ve called you on some of those nights when the shadows were too deep, too strong.

All that is far behind me now, you know. That was somebody else. I’ve made my peace, and I’m not dead.

What do these first names say about us? You’re asking me the question, so:

Anne-Myriam, required to save Claire-Noémie again and again so that she doesn’t die. Just like you’re saving the Rabinowitzes now, by following the trail of that postcard.

What effects have these first names had on our personalities, and on the bond between us, on our relationship that hasn’t always been easy? You have to go and ask me that, damn it.

Now, and for a good few years now, your drive to save me has disappeared. It wasn’t your role. And I’ve stopped trying to kill myself. I don’t resent you for being cold anymore, either, and I hope you’ve stopped thinking I’m infuriating, too. I’m sure you would have used words far stronger than ‘infuriating’ at one point, but you were too polite to do it, even though I deserved it. I gave you such a hard time.

But I know how to be discreet and polite now, too, and you’re not a woman who blends into the wallpaper, or leaves the table early. Quite the opposite, in fact.

I think that, as we both approach forty, we’re only just beginning to get to know each other. Even though we lived together for so many years.

I think Myriam and Noémie never got the chance to begin to get to know each other.

I think we’ve survived our conflicts, and our arguments, and our betrayals, and our inability to understand one another.

I think I would never have been able to write all this to you if you hadn’t sent me that e-mail, with its questions come from the grave.

This is what I think. But I really don’t know. We survived.

And Myriam couldn’t have saved her family.

It wasn’t her fault.

Noémie didn’t have the chance to write.

You and I became writers.

We’ve written, the two of us, with four hands. And it wasn’t easy. But it was beautiful and intense.

I hope so much, Anne, that one day I can be your strength. Your shelter.

A force of light. A force of Claire. Godspeed with the postcard.

A hug and a squeeze to you and Clara.

Love,

c.

P.S.:

A dokh leben oune liebkheit. Dous ken gournicht gournicht zein. To live without affection is not living at all.

Excerpted from The Postcard by Anne Berest, originally published as La carte postale, copyright Anne Berest 2021. Translation by Tina Kover, copyright 2023 Europa Editions.