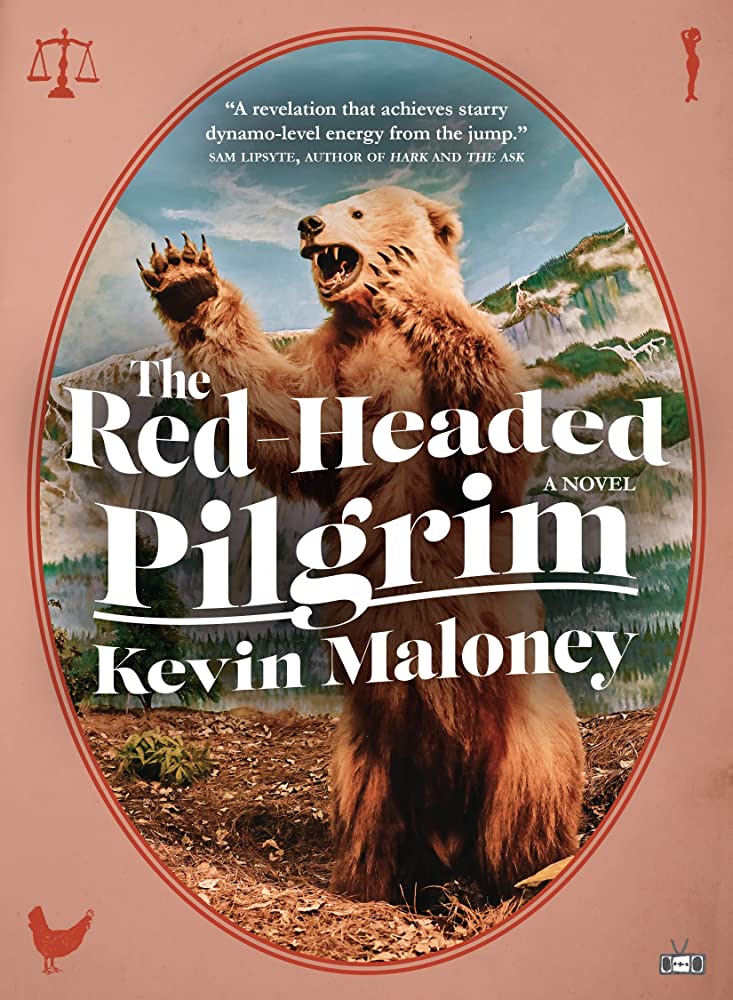

For a certain kind of reader, the prologue to Kevin Maloney’s The Red-Headed Pilgrim will sound familiar. It features a writer approaching middle-age looking back on his life, explaining how he wrote the book you’ve just opened. If you did the summer reading back in AP Literature, you’ve likely already guessed Maloney’s source material.

To this day, Kurt Vonnegut’s influence pervades most American fiction that aims for that elusive combination of being both “literary” and “funny.” Like his indie lit peer Scott McClanahan, Maloney’s writing is deeply indebted to Vonnegut’s mix of heartbreak and humor, but The Red-Headed Pilgrim’s emulation of Slaughterhouse-Five’s opening chapter isn’t just for show; its placement points to the central question of the book: Is it possible to separate your own narrative from the ones you discovered in your formative years?

To this day, Kurt Vonnegut’s influence pervades most American fiction that aims for that elusive combination of being both “literary” and “funny.” Like his indie lit peer Scott McClanahan, Maloney’s writing is deeply indebted to Vonnegut’s mix of heartbreak and humor, but The Red-Headed Pilgrim’s emulation of Slaughterhouse-Five’s opening chapter isn’t just for show; its placement points to the central question of the book: Is it possible to separate your own narrative from the ones you discovered in your formative years?

The novel is a somewhat autobiographical romp across America by a young man named “Kevin Maloney” who “leaves his home and everything he knows and goes looking for God.” Kevin reads On the Road and Howl, Leaves of Grass and Walden, Joseph Campbell and Juddi Krishnamurti. He goes to college, does shrooms, and bugs the philosophy department before dropping out. “I thought the purpose of life was zigzagging back and forth across the country,” he writes, “burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.” And so he zigs and sags, moving 11 times in three years, desperately trying, as Ginsberg would say, “to find out if I had a vision or you had a vision or he had a vision to find out Eternity.”

The novel is a somewhat autobiographical romp across America by a young man named “Kevin Maloney” who “leaves his home and everything he knows and goes looking for God.” Kevin reads On the Road and Howl, Leaves of Grass and Walden, Joseph Campbell and Juddi Krishnamurti. He goes to college, does shrooms, and bugs the philosophy department before dropping out. “I thought the purpose of life was zigzagging back and forth across the country,” he writes, “burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.” And so he zigs and sags, moving 11 times in three years, desperately trying, as Ginsberg would say, “to find out if I had a vision or you had a vision or he had a vision to find out Eternity.”

On the surface, that might sound like several dozen other novels that make up the counterculture canon of Gen X: Brautigan, Hesse, and, yes, Vonnegut. But our main character is not so much Slaughterhouse-Five’s Billy Pilgrim as he is Voltaire’s Candide, with the Beats’ bop kabbala as his own form of Panglossian philosophy. Kevin is a quixotic fool, stumbling through pathetic experiences in the hopes of reaching the enlightenment he’s read so much about. “I decided to hitchhike across America. Sing the body electric. Sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world,” he tells Wendy, a woman he meets in the artistic outpost of Burlington, Vermont. If you’re cringing, that’s the point: Kevin’s supposed vision quest is a prolonged delusion, with our hero assuring himself, over and over again, that he’s seeking transcendence, vowing to escape the mundane existence of suburbia and the “capitalist overlords” of society. But Maloney the author is more honest about our hero’s intentions: “I was a nervous pilgrim on a spiritual quest to lose my virginity.”

On the surface, that might sound like several dozen other novels that make up the counterculture canon of Gen X: Brautigan, Hesse, and, yes, Vonnegut. But our main character is not so much Slaughterhouse-Five’s Billy Pilgrim as he is Voltaire’s Candide, with the Beats’ bop kabbala as his own form of Panglossian philosophy. Kevin is a quixotic fool, stumbling through pathetic experiences in the hopes of reaching the enlightenment he’s read so much about. “I decided to hitchhike across America. Sing the body electric. Sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world,” he tells Wendy, a woman he meets in the artistic outpost of Burlington, Vermont. If you’re cringing, that’s the point: Kevin’s supposed vision quest is a prolonged delusion, with our hero assuring himself, over and over again, that he’s seeking transcendence, vowing to escape the mundane existence of suburbia and the “capitalist overlords” of society. But Maloney the author is more honest about our hero’s intentions: “I was a nervous pilgrim on a spiritual quest to lose my virginity.”

Wendy opens Kevin’s eyes to his own bullshit and eviscerates his literary gods, arguing that “the Beats were a bunch of blowhards who’d misappropriated Buddhist ideology to justify being assholes.” Despite his taste and his highfalutin aspirations, Wendy grows fond of Kevin, and eventually sleeps with him, an experience so overwhelming that Kevin briefly loses consciousness. Despite the sex with Wendy, Kevin feels there must be more out there; after all, Howl doesn’t end with the first sex scene.

Kevin heads to Paris to cosplay as an expat and then finds work on a farm in Oregon, settling into an idyllic life outside of America’s cities and suburbs. But when Wendy begs him to move back to Vermont, promising him all the sex he could ever want, he finds it impossible to turn her down. “Just like that, my agrarian dreams vanished,” Maloney writes. “I wasn’t a transcendentalist; I was a dirty dog.” Wendy gets pregnant, Kevin gets a ring, and it seems like we’re headed for the ending of a Gen X morality tale, with the naive hero putting away childish things and discovering that the real spiritual journey is fatherhood. And we do see glimpses of that, especially in the way Kevin is amazed by his baby daughter, Zoё, believing he’s found in her the nirvana that he’d been seeking for so many years. “It occurred to me for the first time,” Maloney writes, “that the meaning of life might not be zigzagging back and forth across the country for no reason or zapping your brain on magic mushrooms, but this: loving something so much it scares you, as you begin the slow, inevitable process of turning into your father.” It’s a touching moment, one where you can feel a clear-cut narrative arc bending towards a tidy resolution.

But only a few pages later, Kevin is brought back to the real world, where he’s responsible for someone other than himself. Zoё is often inconsolable, screaming at random and without cease, and her parents can’t bring themselves to do anything other than surrender to the sound, sharing cigarettes in the freezing Vermont winter while she cries. “It was fine. Everything was fine. Only it wasn’t. We had a shrieking, shitting roommate we were required by law to take care of, whose greatest talent was eroding our will to live,” Maloney writes. “We were bad parents, but it didn’t matter because we were insane from lack of sleep and nothing mattered. We were ruining Zoё’s life, and she was ruining ours.” This is where Maloney hits his stride, with pages that are sometimes bleak, often surprising, and somehow even funnier than the first half’s comic picaresque thanks to Maloney’s expert comedic timing and his uncanny ability to make even the most universal experiences feel specific to his characters.

To drown out his daughter’s cries and escape his dissolving marriage, Kevin begins working on a novel. In his mind, he’s writing a transgressive epic in the style of his heroes, convincing himself he’s an artist rather than just another unremarkable father. When he finally finishes the manuscript, he’s horrified to find the product “wasn’t so much a novel as a vivid description of various porn sites I’d visited in the past week.” It’s not until his marriage falls apart and his daughter moves away that he brushes against something close to enlightenment, finally grasping what Wendy had suggested years earlier: His Beats-inspired soul-searching was little more than a convenient justification for his juvenile desires. “The 16-year-old version of me was always lurking in there somewhere,” he writes, “watching everything I did, pimple-covered, half a bowl of Cinnamon Toast Crunch in his braces, jerking off at the sexy parts.” Even though he’d convinced himself he was living outside of society’s influence, Kevin slowly learns that he was actually just another passive consumer, one who was eager to step into a ready-made identity rather than define one for himself.

“People aren’t supposed to look back,” Vonnegut writes at the end of that opening to Slaughterhouse Five. “I’m certainly not going to do it anymore.” Thankfully, Maloney is now wise enough to know better.