I’ve had a manuscript locked in a drawer for three and a half years now. It’s a coming-of-age novel about a boy who believes a supernatural force has seized the minds of the adults in his life. He and his best friend confront and defeat the supernatural force, but victory comes at the cost of their innocence—the classic trade-off. I don’t know if it’s my best work, but it’s my favorite. Perhaps inevitably, I’m terrified of ever trying to sell it to someone.

I’m not new to this writing jig. A few weeks ago, I went deep into my hard drive archives and tallied the numbers. Here’s what I learned: over the last 25 years, I’ve finished seven novels, three dozen short stories, and 55 essays. The number of published pieces is, well, much smaller. This is all to say that I’m well acquainted with the creative process, its thralls and its jiltings. There is work that I’ve rushed to share with the world and work that I’ve held back. The hard part is getting wise to which is which.

In college, I pursued a double concentration in both poetry and fiction. That’s how much I wanted to be a writer. At the end of senior year, I won an award from the English Department for one of my short stories. A handful of students were honored at a small reception, and we received $300 checks from Alfred Appel, a professor and author of four books on Vladimir Nabokov (my first literary god). This check, Professor Appel told us, might be the most money you ever earn for a single piece of creative work. He grinned like he was joking. He wasn’t joking.

After college I was lucky enough—or damn fool enough, depending on your perspective—to jet straight off to an MFA program. To afford tuition, I juggled four jobs: I spent a part of each week as a web developer, a departmental admin, a researcher for a magazine, an LSAT teacher, and a tutor. I did most of my writing after midnight. I felt like the luckiest guy in the world.

At one point for a workshop I was paired with Mary Gordon, a thoughtful teacher and tenacious stylist whom I’d heard great things about. You’ll love her, one of my mentors said. Professor Gordon told me in our first private conference: I’m going to be hard on you because I think you’re a good writer. Oh, wow, I said, flattered. I suspect this was a line she delivered to many if not most students. If it was a ploy, it worked: I never thought she was harsh, even when she derided the archaic diction in my stories (a symptom, I will confess, of a raging case of Cormac McCarthyism).

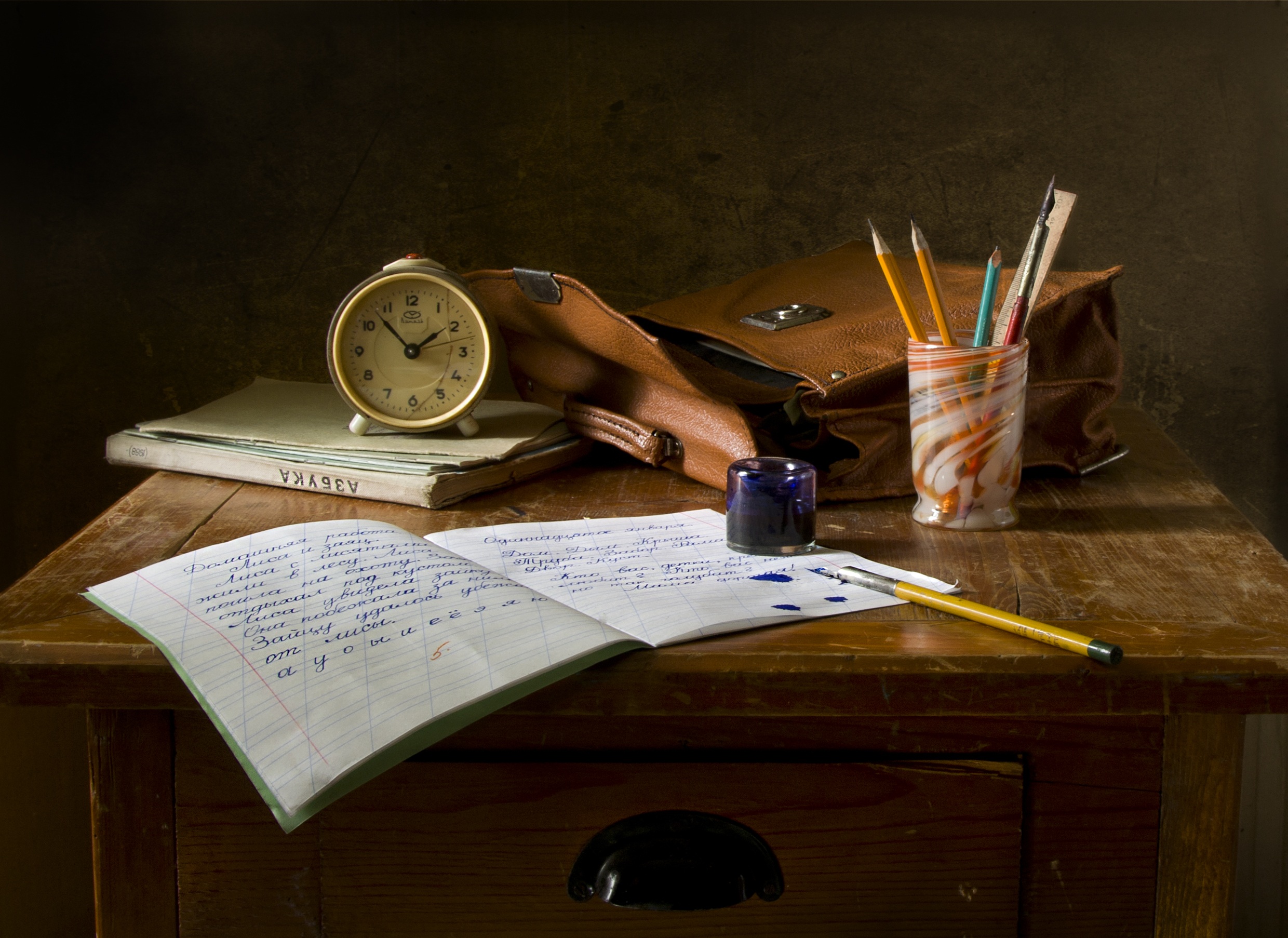

During class one afternoon Professor Gordon said: After I finish a novel, I always put it in a drawer for a year. All of the apprentices in the room sat up a little at this. A year? The disbelief was perceptible, like a shift in the wind. Yes, she insisted, gathering forcefulness as she repeated herself. You must do this with a book. It’s the only way to really figure out if something’s any good. You need space.

Her advice bothered me because it was both wise and inconvenient. Our entire MFA program was oriented around the idea that your thesis would be either a story collections or a novel—either way, you needed a finished manuscript in order to graduate. With what I was paying in tuition, my pockets weren’t deep enough to wait a whole year to figure out if what I wrote was any good. I barreled onward, advice be damned, and when I finished my thesis, I turned it in. I had no time for locked drawers.

I spent five years sharing and revising my first novel. I gathered feedback from agents and editors and friends. I incorporated their suggestions. I signed a contract with an agent. But I never managed to sell the book. The material never quite struck the mark. I only understood why after a critique from my mother, the woman who taught me to read, the relentless reader whose reading habits I first emulated. I had hoped to impress her with what I’d made, the product of all that effort, all that education, all that patience. “I don’t know what I just read,” she wrote on the first page of a print-out of the first chapter.

She did not mean the words in unkindness; she was honestly confused by the novel’s cold open, a poetic description of a cleaning woman as she watches another woman ride a horse down a street. I had long believed that good writing could—would!—connect with anyone. Suddenly, I saw how the problem with my novel was bigger than my novel. I had to accept one of two unacceptable conclusions: either a) my core belief in the universality of good writing was not true; or, b) what I’d labored over for years wasn’t actually good writing. Now that I have the distance of years, I can reread those pages and see, ah, yes. The problem was a little bit of a), and a whole lot of b).

William Faulkner wrote two failed novels (his words) before he famously gave up writing for other people and began to write just for himself. The books he wrote after that volta are the ones that students still read for classes around the world. “Write for yourself” is easy to say, and even easier to understand, but in practice it’s dangerous. If you’re not careful, it leaves you with a hefty tally of novels, stories, and essays, proof that you’re a writer, but confusion about what being a writer has actually done for you.

A few years later I wrote another novel, one that my wife told me had “perfect bones.” I posted to Facebook about how good I felt about her feedback. Other friends, some I knew well, some I hadn’t seen in years, asked to read the manuscript. Eager to share, I had copies of the text printed and bound and mailed to everyone who had inquired. Then I leaned back and waited to hear what people thought. I got at least one or two wonderful emails. A few short notes. But from half of the people, well, I’m still waiting for word.

Did they not like it? Did they not have time to read it? Did they shut the pages at some point and say quietly to an empty room, I don’t know what I just read? I don’t know. Perhaps there is only one thing I can be sure of: anything you put into the world is something that you must accept uncertainty about. Is it enjoyable? Was it understood? It’s impossible to know. It can no longer be your perfect idea. It isn’t even fully yours anymore.

All this has led me to conclude that any given piece of writing must be categorized: the ones you keep, and the ones you share. In order to truly finish a piece you must be ready to know what you want from it. Is it a book that you need many people to read? Or is it something you can lock in a drawer and smile after fondly, knowing you have done what you’ve done, even if no one else sees it? Some of the things that I write are for others, essays like this one. Some of them are just for me, like that novel in the drawer that I love.

I have in truth shared the novel I love with a very select group. My teenage daughter read it in a day and said she wanted more—quite a compliment. My dad said the book’s setting made him think fondly of the town where he (and I) grew up. I sent the novel to a fellow writer, and she said it lifted her heart. I haven’t edited or revised the manuscript in ages but if I close my eyes I can still see the scenes. I feel the words. I don’t have a synopsis and I don’t have a plan and I don’t have an expectation that anyone other than a handful people will ever read it—but what if I told you that this feeling, the feeling of a tale that I felt and then captured in words, is the best feeling I’ve ever had as a writer? The one that I love most? The one that I would never trade, even if it meant somebody paid me a bunch of money for this book in the drawer and all the other ones that I wrote and failed to sell, too?

Nothing feels as good. Not even when someone tells me they’ve read my book and it was great. Not even when an editor writes back to tell me, yes, they’d like to run my essay. Don’t get me wrong or mark me as ungrateful. Those latter moments are great, even necessary at times. But they’re post facto. They’re director’s notes for a part that I’m no longer performing. Like life, art moves on.