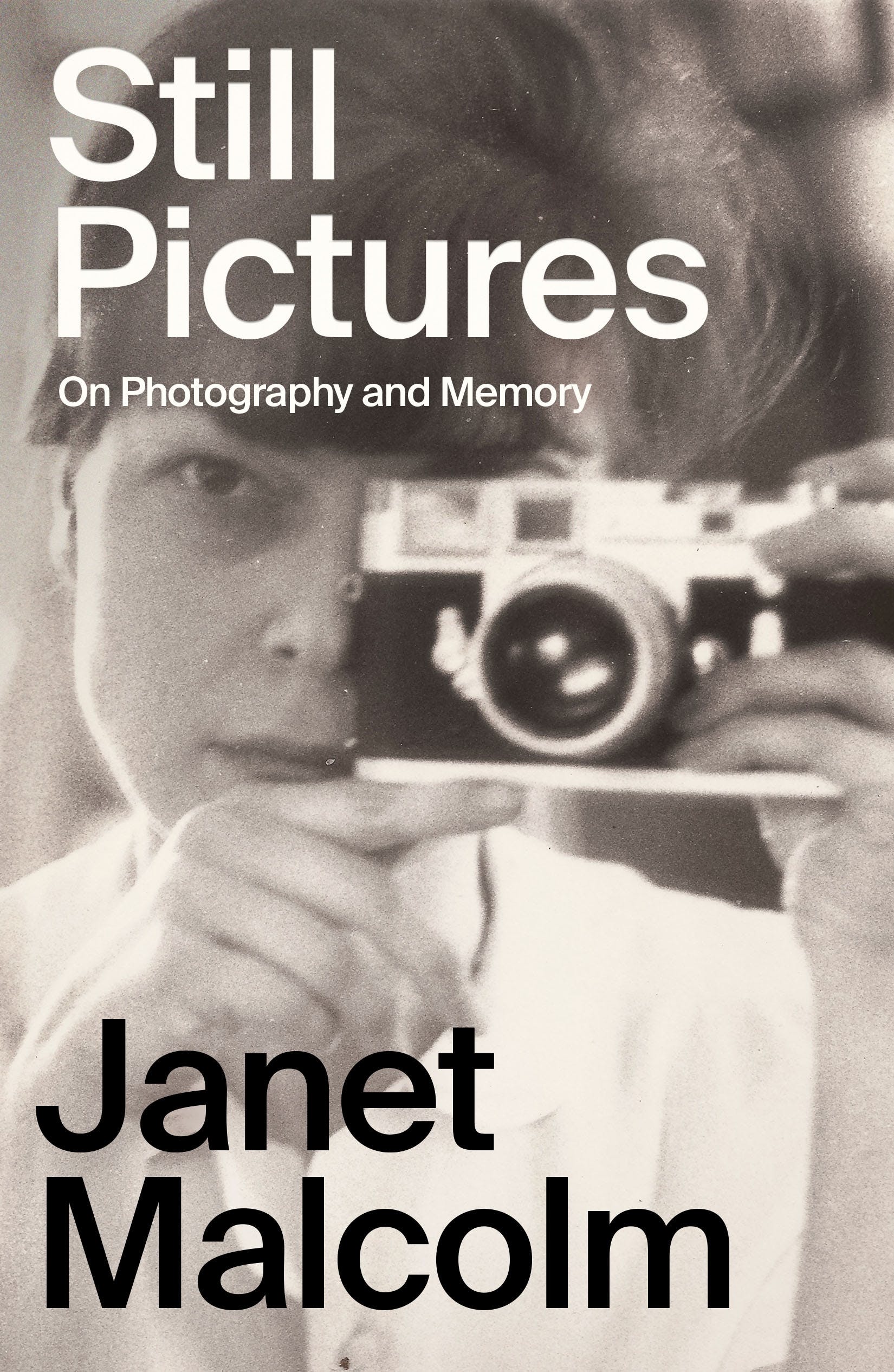

I am looking at a photograph I took on my city walk in search of Janet Malcolm. It shows the entrance to the apartment building on East 72nd Street where Malcolm grew up in what used to be a working-class neighborhood with a large Czech population in Manhattan. Her family moved into a ground-floor unit in 1940, one year after barely escaping the Nazis in Prague. I stare at the picture, hoping it will help me understand the scenes in Malcolm’s new book, Still Pictures, a series of essays based on old photographs. I try to imagine her father, “the gentlest of men,” coming home from an opera, making notes and reading novels, telling his daughters of the bestsellers he expected them to write, and I try to imagine her mother walking out of the building at night “with a coat thrown over her nightgown,” waiting for her daughters to come home—an iron grip that dashed Malcolm’s girlhood chances, on at least one occasion, at love.

But of course I can’t see any of this in my picture. Like Malcolm in her 2001 book, Reading Chekhov, I am the literary pilgrim who left “the magical pages of a work of genius,” then traveled to an “original scene” that can only fall short of my expectations. The photographs that structure Still Pictures come from a box in Malcolm’s apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” My picture is a “New Not Good Photo,” which had nothing to say to me. Malcolm’s old photos go deep; they are like dreams, she says, but not the ones we remember. These dreams flicker, then dissipate into the recesses of our minds. “However, as psychoanalysis has taught us,” she writes in Still Pictures, “it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So, too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.” Pictures give us words, which give us hidden pictures. Is this what Diane Arbus meant when she called a photograph “a secret about a secret”?

But of course I can’t see any of this in my picture. Like Malcolm in her 2001 book, Reading Chekhov, I am the literary pilgrim who left “the magical pages of a work of genius,” then traveled to an “original scene” that can only fall short of my expectations. The photographs that structure Still Pictures come from a box in Malcolm’s apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” My picture is a “New Not Good Photo,” which had nothing to say to me. Malcolm’s old photos go deep; they are like dreams, she says, but not the ones we remember. These dreams flicker, then dissipate into the recesses of our minds. “However, as psychoanalysis has taught us,” she writes in Still Pictures, “it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So, too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.” Pictures give us words, which give us hidden pictures. Is this what Diane Arbus meant when she called a photograph “a secret about a secret”?

Still Pictures is all about secrets, but not the ones we tell on purpose. (Those, Malcolm tells us, she keeps to herself.) In Freudian psychoanalysis, the patient is asked to free associate, to say aloud whatever comes to her mind. She might tell the analyst about a dream, Malcolm writes, then “blurt out some trivial image or idea or recollection (I went to the cleaners yesterday) that is entirely unrelated to the dream—and turns out to be the key to its meaning.” In Still Pictures, Malcolm associates from one picture to the next, one memory to the next. But free association turns out to be immensely difficult. The writer resists. “As I try to portray [my mother],” she writes, “I come up against what must be a strong resistance to doing so.” She writes a couple of false starts before she is ready to speak from the heart, the fear of which, she reminds us, is deep-seated in us all. She can only hope some truth will leak out of her associations, as she listens for the words in her pictures.

Still Pictures is all about secrets, but not the ones we tell on purpose. (Those, Malcolm tells us, she keeps to herself.) In Freudian psychoanalysis, the patient is asked to free associate, to say aloud whatever comes to her mind. She might tell the analyst about a dream, Malcolm writes, then “blurt out some trivial image or idea or recollection (I went to the cleaners yesterday) that is entirely unrelated to the dream—and turns out to be the key to its meaning.” In Still Pictures, Malcolm associates from one picture to the next, one memory to the next. But free association turns out to be immensely difficult. The writer resists. “As I try to portray [my mother],” she writes, “I come up against what must be a strong resistance to doing so.” She writes a couple of false starts before she is ready to speak from the heart, the fear of which, she reminds us, is deep-seated in us all. She can only hope some truth will leak out of her associations, as she listens for the words in her pictures.

The first family photograph Malcolm looks at in Still Pictures is one of those drab little photos that doesn’t speak. It is a picture of Malcolm at two or three years old, sitting on a stoop, exhibiting a preternatural charm. But Malcolm doesn’t identify with the little girl; she stirs in her no feelings of identification. Instead, the picture sends Malcolm to a painting and, eventually, to her first memory. She is at a village festival. It is a fine day in early summer, and little girls in white dresses are walking in a procession, strewing rose petals. Malcolm wants to join the procession, but she has no basket of petals. Her aunt comes to her rescue, filling a basket with white petals from a bush in her garden. Immediately, though, she notices that the petals in the basket are not roses; they are peonies. “I am unhappy,” Malcolm writes. “I feel cheated. I feel that I have not been given the real thing, but something counterfeit.”

In her 1990 book, The Journalist and the Murderer, an apercu on the writer-subject relationship (in which, she argues, the writer exercises an “unholy power” over the subject), Malcolm recalls: “Almost from the start, I was struck by the unhealthiness of the journalist-subject relationship, and every piece I wrote only deepened my consciousness of the canker that lies at the heart of the rose of journalism.” Am I reaching when I see in this ruined rose of journalism an echo of her earliest memory? It is another flawed flower. At the festival, she doesn’t have the rose that would let her join the other girls in the procession, and the rose she wants to give the reader, journalism corrupts. Later in Still Pictures, Malcolm wonders if she became a journalist because of her ability to imitate her mother’s charm, a helpful skill for a reporter who needs her subjects to talk to her. But I wondered about other possibilities: Did she become a journalist because she felt—fundamentally, perpetually—like an outsider? A writer is set apart, fated to exist at a distance from the subjects she writes about. What if Malcolm would have found rose petals in her basket that early summer day? Would everything have been different?

In her 1990 book, The Journalist and the Murderer, an apercu on the writer-subject relationship (in which, she argues, the writer exercises an “unholy power” over the subject), Malcolm recalls: “Almost from the start, I was struck by the unhealthiness of the journalist-subject relationship, and every piece I wrote only deepened my consciousness of the canker that lies at the heart of the rose of journalism.” Am I reaching when I see in this ruined rose of journalism an echo of her earliest memory? It is another flawed flower. At the festival, she doesn’t have the rose that would let her join the other girls in the procession, and the rose she wants to give the reader, journalism corrupts. Later in Still Pictures, Malcolm wonders if she became a journalist because of her ability to imitate her mother’s charm, a helpful skill for a reporter who needs her subjects to talk to her. But I wondered about other possibilities: Did she become a journalist because she felt—fundamentally, perpetually—like an outsider? A writer is set apart, fated to exist at a distance from the subjects she writes about. What if Malcolm would have found rose petals in her basket that early summer day? Would everything have been different?

In the first picture (on a stoop in Prague), she is like everyone else, and she looks happy; in the second picture (on a train leaving Prague), she is out of sorts, as if the child knows that something has been lost, and nothing will be the same. Growing up speaking Czech in New York, she doesn’t belong to any culture. For the first year, her English is limited, and whenever her teacher says “Goodbye, Children,” she thinks “Children” must be a student’s name, hoping one day the teacher might say “Goodbye, Janet.” There are memories, too, of being left out of love, and memories of watching some charismatic girl at the center of things while Malcolm remained part of the “ordinary background.” But there is no self-pity in the lines her memory speaks; she simply accepts her outsiderness (as she accepted her brilliance, writes Ian Frazier in the book’s introduction) as no big deal.

Lingering on the peony-petal memory a bit longer, my mind wanders to her parents, who are absent from this moment of exclusion. If a kind aunt hadn’t come to her aid, would one of them have brought her a basket? As the pieces unfold, Malcolm includes memories of her mother’s goodness, warmth, unselfishness, vivacity (hiding, she says, an inner deadness of spirit), as well as her mother’s histrionics and depression, her frustration with Malcolm when she didn’t write from Michigan, where she was a college student, and when she did write home, her mother’s frustration with Malcolm’s ironic detachment. In a particularly revealing moment, Malcolm remembers the day she exploded at her father, in response to which her mother exploded at her. “A flash of insight came to me,” she writes. “I saw my mother’s all-powerful place in the family.”

Above all, Malcolm is preoccupied with her mother’s charm. “She belonged to her time,” Malcolm writes, “and this was a time when women worshipped men without ever quite coming out and saying so. It has taken me a long time to understand the implications of her legacy of charm.” This passage says obliquely what Malcolm says directly in her 2011 Paris Review interview: “Showing off to straight men remained a delight and a necessity to women of my generation,” Malcolm says. “Our writing had a certain note.” Then, Malcolm stops herself. “You have led us into deep waters,” she says. “This is a complex and murky subject. Perhaps we can cut through the haze together.” In Still Pictures, the air in some ways has cleared; in others, the past remains a dense fog. But she is no longer out of sorts. She has accepted the strangeness of it all.

Hell isn’t other people; hell is our need for other people, wrote Adam Phillips, the British psychoanalyst and essayist. Still Pictures proceeds with this wisdom. “Autobiography is a misnamed genre,” Malcolm writes, because memory never tells the whole story, and one cannot speak for oneself without speaking for other people. Her book is impossible without the biographies of people who made her life possible. Beyond her immediate family, she draws portraits of her grandmother, whom she never met; her aunt and uncle, who, like Malcolm’s parents, changed their names to avoid antisemitism in New York; her teacher at Czech School in Yorkville; her counselors at Camp Happyacres; four old women who existed at the edges of her girlhood consciousness; and portraits of boys and men, some central and others peripheral, like Jiri Kašpárek, who took the picture of Malcolm and her parents on the train leaving Prague, then stayed behind and survived capture and imprisonment for his anti-Nazi activities. Throughout Still Pictures—quietly, hauntingly—there are half-drawn portraits and missing portraits of people who died at Auschwitz. Malva Schablin, one of the four old women, always wore black, and everyone who knew her knew why.

What did a young Malcolm understand about the fate she escaped? It’s a mystery that stays in her mind. She remembers the dread that filled her when she looked at a comic-book image of a lost child facing a tree with a path on either side—life or death—but most of the time she was preoccupied with her girlhood concerns in a relatively safe New York, going to the movies, falling in love with boys and at least one girl. She chases love to escape the weight of the past, until love makes room for her to grieve that past. In one memory, she is sitting at the table with her husband G., who, as a soldier in World War II, liberated a Nazi concentration camp. For a long time, she says, he couldn’t talk about that experience, and when he wrote his memoir about the war, he didn’t write about the camp. But one night, at the dinner table with Malcolm, he suddenly talked. “He cried as he described what he saw, and I cried with him,” writes Malcolm, and one feels it might be the first time she did.

Hell might be our need for other people, but other people are also the only possibility of heaven (which, Ian Frazier told Malcolm near the end of her life, can’t be ruled out). Malcolm’s work proceeds with this wisdom, too—she is known for her distrust of biography, but she could be equally well-known for her insistence that the writer identify with and have affection for her subject. She didn’t want final judgments; she wanted honest conversation. Even her harshest lines—”Every journalist not too stupid or full of himself to know what’s going on know what he does is morally indefensible”—are proposals for engagement. She wanted us to join her in the haze—or, as in the case of her friendship with Frazier, on a beach in Staten Island, looking for shards of glass, following whatever caught her eye.

“She had a knack for knowing which ephemera to save,” writes Frazier, and like her father, who used to pick certain small, frail, white wildflowers that she had never thought to notice, Malcolm saw in the ephemera that drew her attention—a leaf that looked like it had been through something, a weed that appeared “epic and battled and dignified”—chances to exercise awe. Everywhere in her prose there are numinous things, like in that passage about her father’s wildflowers. To find them, follow Malcolm in search of Chekhov, for whom she had the greatest admiration, then read her collection essays, The Purloined Clinic, in which there are subjects she identifies with so closely she calls them doubles. Go back to Psychoanalysis, at the center of which is a writer-subject relationship marked by mutual respect and affection, and see the line between that book and this one, Still Pictures, her last. “The gold is dross,” she learned in psychoanalysis. “Memory only speaks some of its lines.” What to do, then, but look long enough to find interesting shards that wash up on shore? Malcolm never stopped looking, and she never stopped assembling what she found.

“She had a knack for knowing which ephemera to save,” writes Frazier, and like her father, who used to pick certain small, frail, white wildflowers that she had never thought to notice, Malcolm saw in the ephemera that drew her attention—a leaf that looked like it had been through something, a weed that appeared “epic and battled and dignified”—chances to exercise awe. Everywhere in her prose there are numinous things, like in that passage about her father’s wildflowers. To find them, follow Malcolm in search of Chekhov, for whom she had the greatest admiration, then read her collection essays, The Purloined Clinic, in which there are subjects she identifies with so closely she calls them doubles. Go back to Psychoanalysis, at the center of which is a writer-subject relationship marked by mutual respect and affection, and see the line between that book and this one, Still Pictures, her last. “The gold is dross,” she learned in psychoanalysis. “Memory only speaks some of its lines.” What to do, then, but look long enough to find interesting shards that wash up on shore? Malcolm never stopped looking, and she never stopped assembling what she found.