Blurb is a funny sounding word. It’s phonetically unappealing, beginning and ending with unattractive voiced bilabial stops, and its definition—an advertisement or announcement, especially a laudatory one—carries some of the same meaning as another unattractive word, blubber, which evokes excess in its dual definition as both an expostulation of unrestrained emotion as well as excess fat. For these reasons alone, any sensible person should beware of blurbs.

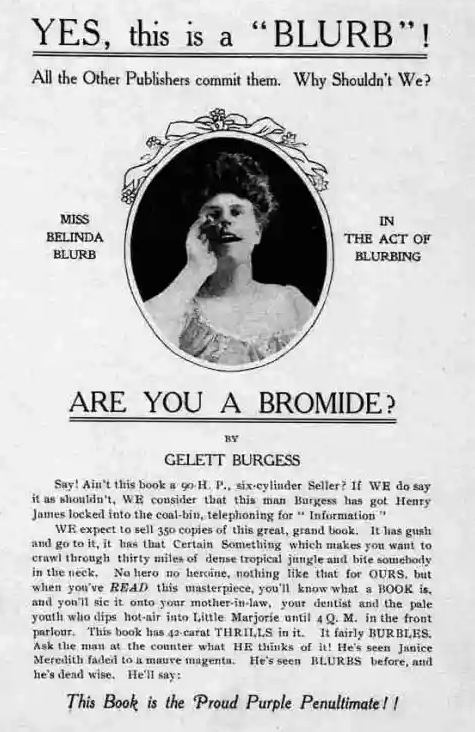

First, an origin story. The year is 1907, and author and humorist Gelett Burgess has been invited to the annual American Booksellers Association dinner to present copies of his new book, Are You a Bromide? Burgess presented a mock cover for the book, featuring a made-up “spokesperson” named Miss Belinda Blurb, whose image was purportedly lifted from a dental advertisement “in the act of blurbing.” She shouts, hand cupped around her mouth, that the book has “gush and go to it,” and a “certain something which makes you want to crawl through thirty miles of dense tropical jungle and bite somebody in the neck.” This was the first use of the word blurb as we know it today. As a noun, Burgess himself defined a blurb as “a flamboyant advertisement; an inspired testimonial”; as a verb, “to flatter from interested motives; to compliment oneself.”

Blurbs had been used in publishing long before they had a name. One of the earliest examples of a book blurb in the United States was penned by none other than Ralph Waldo Emerson. It appeared on the jacket of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 1855. The blurb was taken from a letter that Emerson had sent to Whitman, and which Whitman included on the spine of his book; it salutes his promise as a poet, and reads: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career, RW Emerson.”

Blurbs had been used in publishing long before they had a name. One of the earliest examples of a book blurb in the United States was penned by none other than Ralph Waldo Emerson. It appeared on the jacket of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 1855. The blurb was taken from a letter that Emerson had sent to Whitman, and which Whitman included on the spine of his book; it salutes his promise as a poet, and reads: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career, RW Emerson.”

Blurbing has always had discontents. In 1936, George Orwell decried the use of blurbs in his essay “In Defense of the Novel.” He feared for the novel’s “lapse in prestige,” for which he partly blamed “hack reviews” and “the disgusting tripe that is written by the blurb-reviewers,” which were dishonest and served the interests of the publishers. Half a century later, speaking to students in MIT’s writing program in 1991, Camille Paglia called “for an end to the corrupt practice of advance blurbs on books.” She maintained that “this advance blurb thing is absolutely appalling, because it means that they send your book around to your friends, they scratch your back, and you scratch theirs. This is part of the coziness of the profession that I think has just been pernicious… That has got to stop.”

The notorious and satirical Spy magazine, which covered entertainment and media from 1986 to 1998, had a feature called “log rolling in our time” that demonstrated Paglia’s contention. Editors Graydon Carter and Kurt Anderson would juxtapose one author’s blurb against another, showing the scratch-your-back-operating principle in practice. For instance:

“A seduction through language, a mosque without mask.”—Cynthia Ozick on Edmund White’s Caracole

“The best American writer to have emerged in recent years.”—Edmund White on Ozick’s The Cannibal Galaxy

Few writers decline to blurb a book since, more often than not, they have been personally appealed to by the author, or the author’s editor or agent (both of whom they are likely to know). More importantly, the blurber’s name will appear on the book in conjunction with the author and other blurbers, so the blurb is as much an advertisement for the blurber as it is an endorsement of the book.

In a recent essay on the controversial publication of American Dirt, critic Christian Lorentzen questioned the validity of the glowing blurbs that the book received from such literary luminaries as Stephen King, Sandra Cisneros, and John Grisham. “The blurb system is corrupt on its face,” Lorentzen writes. “Blurbs may be earnest and true, but they are always the product of favors being called in: from authors’ friends, from agents’ other clients, from publishers’ other authors. Everyone knows this.”

In a recent essay on the controversial publication of American Dirt, critic Christian Lorentzen questioned the validity of the glowing blurbs that the book received from such literary luminaries as Stephen King, Sandra Cisneros, and John Grisham. “The blurb system is corrupt on its face,” Lorentzen writes. “Blurbs may be earnest and true, but they are always the product of favors being called in: from authors’ friends, from agents’ other clients, from publishers’ other authors. Everyone knows this.”

Until recently, publishing’s most prolific blurber—the king of the blurbs—has been author Gary Shteyngart, who in 2014 claimed to have blurbed over 150 books. In a 2014 New Yorker essay, he abdicated his throne, saying “the volume of requests has exceeded my abilities, and I will be throwing my ‘blurbing pen’ into the Hudson River.” Despite this proclamation, he said he would go on blurbing for “all former, present, and future students of mine at Columbia University; authors of my Random House editor, David Ebershoff; authors of my agent, Denise Shannon; my B.F.F.s” In other words, all the usual suspects decried by Paglia.

During her tenure, former London Review of Books editor Mary-Kay Wilmers instituted a policy that any sentence in a review that could be used as a quote on a book was to be cut. When asked why, she answered: “Those are never good sentences.” David Foster Wallace shared Wilmers’s aversion to the language of blurbing. At a public reading in 2004, when questioned about the blurbs that adorn the jackets of his own novels, Wallace coined the term “blurbspeak,” which he defined as “a very special subdialect of English that’s partly hyperbole, but it’s also phrases that sound really good and are very compelling in an advertorial sense, but if you think about them, they’re literally meaningless.” This did not, however, stop him from providing blurbs for many books including Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and his friend Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, which he called “a testament to the range and depth of pleasures great fiction affords.”

During her tenure, former London Review of Books editor Mary-Kay Wilmers instituted a policy that any sentence in a review that could be used as a quote on a book was to be cut. When asked why, she answered: “Those are never good sentences.” David Foster Wallace shared Wilmers’s aversion to the language of blurbing. At a public reading in 2004, when questioned about the blurbs that adorn the jackets of his own novels, Wallace coined the term “blurbspeak,” which he defined as “a very special subdialect of English that’s partly hyperbole, but it’s also phrases that sound really good and are very compelling in an advertorial sense, but if you think about them, they’re literally meaningless.” This did not, however, stop him from providing blurbs for many books including Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and his friend Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, which he called “a testament to the range and depth of pleasures great fiction affords.”

Even our resident blurber Shteyngart agrees with Wallace’s claim that hyperbole is inherent to the form. Making an appearance as his charming, irrepressible self in the documentary short “Shteyngart Blurbs,” the author defends such exaggeration: “No hyperbole can be hyperbolic enough because very few people want to read this stuff.” (Shteyngart’s latest novel, Our Country Friends is graced by six blurbs, one of which, from Less author Andrew Sean Greer, hails it as “a masterpiece.”)

Even our resident blurber Shteyngart agrees with Wallace’s claim that hyperbole is inherent to the form. Making an appearance as his charming, irrepressible self in the documentary short “Shteyngart Blurbs,” the author defends such exaggeration: “No hyperbole can be hyperbolic enough because very few people want to read this stuff.” (Shteyngart’s latest novel, Our Country Friends is graced by six blurbs, one of which, from Less author Andrew Sean Greer, hails it as “a masterpiece.”)

As Shteyngart notes in the documentary, when a galley arrives, many blurbers read no more than the publisher’s plot summary which is written by the editor or publicity department or both. It is then quite easy for a blurber to riff off of what they’ve been supplied. Blurbs generally share a common format across all genres of books: Author praise: “A talented writer who…”; “Her intelligence is such that….” One-word gushing: “electrifying”; “gripping.” Two-word slobbering: “wickedly smart”; “hauntingly beautiful.” Dubious equivalences: “as satisfying as it is unsettling”; “as sharply conceived as it is brilliantly written.”

Aside from the irony inherent in Shteyngart’s quip that “no hyperbole can be hyperbolic enough,” his assertion is insightful because language so easily crosses the threshold from hyperbole to hysteria. When the goal is to pump up the volume “high enough” so it can be heard far and wide, blurbers tend to say practically anything, confounding the boundaries between true and false in the hopes of grabbing attention. This frequently leads to situations where there is but the most tenuous connection between the work at hand and the blurb. Generally, blurbers obfuscate the reality of the work. Critics—the good ones, at least—don’t.

A case study. The Booker-winning English author Ian McEwan’s latest novel, the ominously titled Lessons, received laudatory blurbs upon its publication last year. Taylor Antrim, extolled the novel as “beautifully written”; Claire Messud hailed it as “brilliant”; and Steven G. Kellman called it “a masterpiece of modulation among pathos.” But critic Ryan Ruby was not swayed by these descriptors. In his review, appearing in the New Left Review, Ruby finds McEwan’s prose is in fact not beautiful, and the novel not brilliant. It is actually, in his estimation, a compilation of: “first-order cliches (“trying to escape his own demons”), mixed metaphors (“ten on the pain spectrum”), limp similes (“Some love affairs comfortably and sweetly rot. Slowly, like fruit in a fridge”), oxymorons (“a settled, expansive mood”), jejune diction (“the creepy shifting shadows”), and pomposities (“They rose in his thoughts as a black hammerhead cloud of international disorder”). As for larger structural issues, he notes, “Within the first fifty or so pages, Roland [the protagonist] experiences no fewer than three portentous epiphanies, none of which turn out to have any bearing on the subsequent four hundred, as though they were narrative coupons McEwan cut out but forgot to cash in,” leading his to the conclusion that the novel is not a “masterpiece,” but “mediocre” at best.

A case study. The Booker-winning English author Ian McEwan’s latest novel, the ominously titled Lessons, received laudatory blurbs upon its publication last year. Taylor Antrim, extolled the novel as “beautifully written”; Claire Messud hailed it as “brilliant”; and Steven G. Kellman called it “a masterpiece of modulation among pathos.” But critic Ryan Ruby was not swayed by these descriptors. In his review, appearing in the New Left Review, Ruby finds McEwan’s prose is in fact not beautiful, and the novel not brilliant. It is actually, in his estimation, a compilation of: “first-order cliches (“trying to escape his own demons”), mixed metaphors (“ten on the pain spectrum”), limp similes (“Some love affairs comfortably and sweetly rot. Slowly, like fruit in a fridge”), oxymorons (“a settled, expansive mood”), jejune diction (“the creepy shifting shadows”), and pomposities (“They rose in his thoughts as a black hammerhead cloud of international disorder”). As for larger structural issues, he notes, “Within the first fifty or so pages, Roland [the protagonist] experiences no fewer than three portentous epiphanies, none of which turn out to have any bearing on the subsequent four hundred, as though they were narrative coupons McEwan cut out but forgot to cash in,” leading his to the conclusion that the novel is not a “masterpiece,” but “mediocre” at best.

The often radical divergence between blurbs and the reality of the work is not exclusive to fiction. Elisa Gabbert has published six collections of poetry, as well as essays and criticism. The blurbs for her recently released collection Normal Distance state that Gabbert is a “restless thinker” calling her new work “casually brilliant” and a “must read” that “cannot be forgotten long after you close its pages.” But as with McEwan, a read through the collection shows these claims can’t quite be substantiated. I don’t want to say that an occasional poem in this slim volume doesn’t stake a claim to be entertaining and provide fleeting mental stimulation approaching pleasure, but it’s doubtful that any of them reach the “highest lyric aim,” as blurber Kaveh Akbar claims. Certainly there is no textual evidence to back up the assertion that the work is “pierced with a blazing conversation toward philosophy,” per Bianca Stone’s blurb. This is not, as Dorthea Lasky declares in her blurb, a “must-read” book, nor is it a work “full of force and cannot be forgotten long after you close its pages.” It is a work replete with inane and silly sentences such as, “You can’t attend your own funeral, but you have to attend your own death,” and “I spend a lot of time waiting around for something wonderful to happen.” On any level of analysis, the poems in this collection—the majority of them reminiscent of throwaway tweets and the jejune work of Instapoet Rupi Kaur—just don’t merit the praise they are given by blurbers.

The often radical divergence between blurbs and the reality of the work is not exclusive to fiction. Elisa Gabbert has published six collections of poetry, as well as essays and criticism. The blurbs for her recently released collection Normal Distance state that Gabbert is a “restless thinker” calling her new work “casually brilliant” and a “must read” that “cannot be forgotten long after you close its pages.” But as with McEwan, a read through the collection shows these claims can’t quite be substantiated. I don’t want to say that an occasional poem in this slim volume doesn’t stake a claim to be entertaining and provide fleeting mental stimulation approaching pleasure, but it’s doubtful that any of them reach the “highest lyric aim,” as blurber Kaveh Akbar claims. Certainly there is no textual evidence to back up the assertion that the work is “pierced with a blazing conversation toward philosophy,” per Bianca Stone’s blurb. This is not, as Dorthea Lasky declares in her blurb, a “must-read” book, nor is it a work “full of force and cannot be forgotten long after you close its pages.” It is a work replete with inane and silly sentences such as, “You can’t attend your own funeral, but you have to attend your own death,” and “I spend a lot of time waiting around for something wonderful to happen.” On any level of analysis, the poems in this collection—the majority of them reminiscent of throwaway tweets and the jejune work of Instapoet Rupi Kaur—just don’t merit the praise they are given by blurbers.

While Stephanie LaCava does not have as extensive an oeuvre as McEwan or Gabbert, her latest novel I Fear My Pain Interests You boasts 25 blurbs on its Amazon page, including notices from Tom McCarthy, Tao Lin, and Merve Emre. Which is surprising because the novel is of limited scope, lacking breadth and depth. While there is pretty prose to be found throughout, as well as some snappy dialog, it’s hard to imagine what evidence one would present to say that is “a cool, cut throat razor of a novel” (whatever that means). Nor, when reading it, is there any reason for you to “fear [LaCava’s] book will destroy you.” It also seems wrong to state that the novel, narrated by a young woman named Margot, is an exploration of “a mind molded by generational trauma” because Margot is nepo baby, and since the actual drama of the book takes place off the grid in remote Montana, it makes no sense to say that the novel explores “what it means to be a woman in the world.”

While Stephanie LaCava does not have as extensive an oeuvre as McEwan or Gabbert, her latest novel I Fear My Pain Interests You boasts 25 blurbs on its Amazon page, including notices from Tom McCarthy, Tao Lin, and Merve Emre. Which is surprising because the novel is of limited scope, lacking breadth and depth. While there is pretty prose to be found throughout, as well as some snappy dialog, it’s hard to imagine what evidence one would present to say that is “a cool, cut throat razor of a novel” (whatever that means). Nor, when reading it, is there any reason for you to “fear [LaCava’s] book will destroy you.” It also seems wrong to state that the novel, narrated by a young woman named Margot, is an exploration of “a mind molded by generational trauma” because Margot is nepo baby, and since the actual drama of the book takes place off the grid in remote Montana, it makes no sense to say that the novel explores “what it means to be a woman in the world.”

The authors under discussion all have accomplishments behind them: McEwan is of course known for his 2001 Booker-nominated novel Atonement, as well as other deservedly lauded novels; in addition to being a published poet and critic, Gabbert writes the “On Poetry” column for the New York Times and is the author of two accomplished essay collections, including the remarkable The Unreality of Memory; and LaCava’s novel The Superrationals show signs of literary style and agility. Because reputation gathers its own momentum, when there is a blip in an author’s output, a blurber undertaking to write about it may be under the sway of the previous good work, leading to them to see the current work through rose-colored glasses. Which may explain the effusive positive blurbs given to the aforementioned books.

The authors under discussion all have accomplishments behind them: McEwan is of course known for his 2001 Booker-nominated novel Atonement, as well as other deservedly lauded novels; in addition to being a published poet and critic, Gabbert writes the “On Poetry” column for the New York Times and is the author of two accomplished essay collections, including the remarkable The Unreality of Memory; and LaCava’s novel The Superrationals show signs of literary style and agility. Because reputation gathers its own momentum, when there is a blip in an author’s output, a blurber undertaking to write about it may be under the sway of the previous good work, leading to them to see the current work through rose-colored glasses. Which may explain the effusive positive blurbs given to the aforementioned books.

I don’t think blurbers believe they are doing a disservice to either the authors they blurb or the reading community when they blurt out their praise since within the blurb ecosystem it is generally understood (perhaps cynically) that “blurbspeak” is, as Wallace noted, “literally meaningless.” (And the jury is still out as to how much they actually help increase book sales.)

For better or worse, blurbs are here to stay. But blurbers who follow the Shteyngartian operating principle (“no hyperbole can be hyperbolic enough”) risk exposing themselves to accusations of lack of critical discernment, or integrity, or both. And, because most blurbs emblazoned on a book’s front and back cover (or on Amazon) tend to have, at best, a tenuous relation to the reality of the text, the final watchword for readers who turn to them when considering a purchase should be: caveat emptor.