And I asked him...

Baby, baby, be easy, so easy, because your father is hard.

And I craved things…

To fuck but not his daddy, and so I ate peanut butter-banana sandwiches for breakfast, lunch, and dinner and vanilla ice cream inside of espresso cups. Because the protein made the baby strong, because the ice cream with all its fat was good for the brain. His brain. My brain.

Craved the days to go slow so time was mine. And in Texas the days were slow and the air thick. The cicadas, the frogs, the javelinas, the deer, the possums, the snakes, the scorpions all had their clocks trampling, buzzing, screeching, in and out of the land I occupied. Swayed on the hammock on my porch listening to them mate, fight, and call each other as I savored the sweet vanilla Blue Bell ice cream.

Baby, baby, be easy on me, please.

And the mothering myths…

And they said…the love affair is instant. It wasn’t. Your body will know what to do. It didn’t. Your maternal instincts will kick in. Ha! don’t worry about money. I did. babies bring fortune. So much debt.

And the truths I wasn’t told…

Babies want to live. They will meet you halfway, always. They don’t need all the bullshit you buy them. Babies listen if you listen. Breast-feeding hurts like a motherfucker. And no, I didn’t do it wrong. I did everything right and still…

And the women helped and said things…

My son came late and large. I had a birthing plan and was set to go natural. Took Bradley Method classes and watched videos of women squatting in the forests and pushing out babies like they were taking a shit. Women having orgasms as the baby pushed through the birth canal. That will be me, I said. I am that kind of woman who would trust her body to do the work it had to do. And then the contractions came and they didn’t repeat but went continuous, one long piano note of steady ache. No water break. No dilation. And I could feel the baby’s head wedged in the canal in a way that I could barely walk or stand. But I have a birthing plan, I said to anyone who would listen. I printed multiple copies for everyone who would read it.

And then this nurse in her eighties, it was the last day on the job, said, Kid I need you to do some squats.

I can’t!

Do it with me.

And so I did. And my body, a closed fist was open, palms up.

You’re gonna have an emergency C-section. You can make it hard for yourself and try to follow your plan or tell your doctor you want a C-section.

Can I trust you, white lady?

Countless articles say that hospitals push C-sections on women.

My doctor, a Puerto Rican from New Jersey who grew up in the projects had yet to arrive. She was someone I trusted. She knew how racist medicine is.

The spry nurse had bright white hair and high-top white sneakers. She had started nursing school in her sixties after her husband died and college was free for seniors. She had a stern voice and the softest hands.

That nurse saved my life.

I almost died.

When they opened me up they found an infection. I went to ICU for three days. Had a blood transfusion. My son in NICU being monitored: ten pounds four ounces. A giant among the preemies. My husband and mother were allowed to visit thirty minutes, two times a day. My terrified husband who spoke no English and did not have the capacity to keep track of doctors, the medicines, the bills, instead took photos of the alien baby attached to the machines and printed them out, taping them on the wall by my bed.

Isn’t he beautiful, he said.

No.

I want to breastfeed. I said repeatedly to the ICU doctors who did not care that I needed to pump. And dump. Pump and dump—la leche de oro was now toxic because I was on so many drugs.

I will never be able to catch up with him, I said.

My plan—to be a natural mother, unlike my grandmother who famously rubbed her nipples with camphor so babies rejected her milk.

My plan was to recover from birth in a day or two and strap him on my back and go on with life as usual.

My plan was to have them dim the lights of my room and play my soothing playlist with some Lauryn Hill, India Arie and Si*Sé. And have my mom feed me ice chips, and my son was supposed to come out like it did for my friend Tamara, who she said that when it came, it slipped out like a bar of soap slips from one’s hands in the shower.

For months, friends would visit and call me and say, OMG Angie, you almost died.

I almost died. I almost died. I almost died.

And when my son came to me…

I was thirty-five, and my ob-gyn called my pregnancy geriatric. At the time I loved my childfree life. But you see I had made a promise. When I was twenty-six, I was pregnant, and I told that baby who appeared to me in a dream and who happens to look a lot like my son does now… I said, Baby, baby, I am sorry but I’m not ready for you, come back, okay?

And he did.

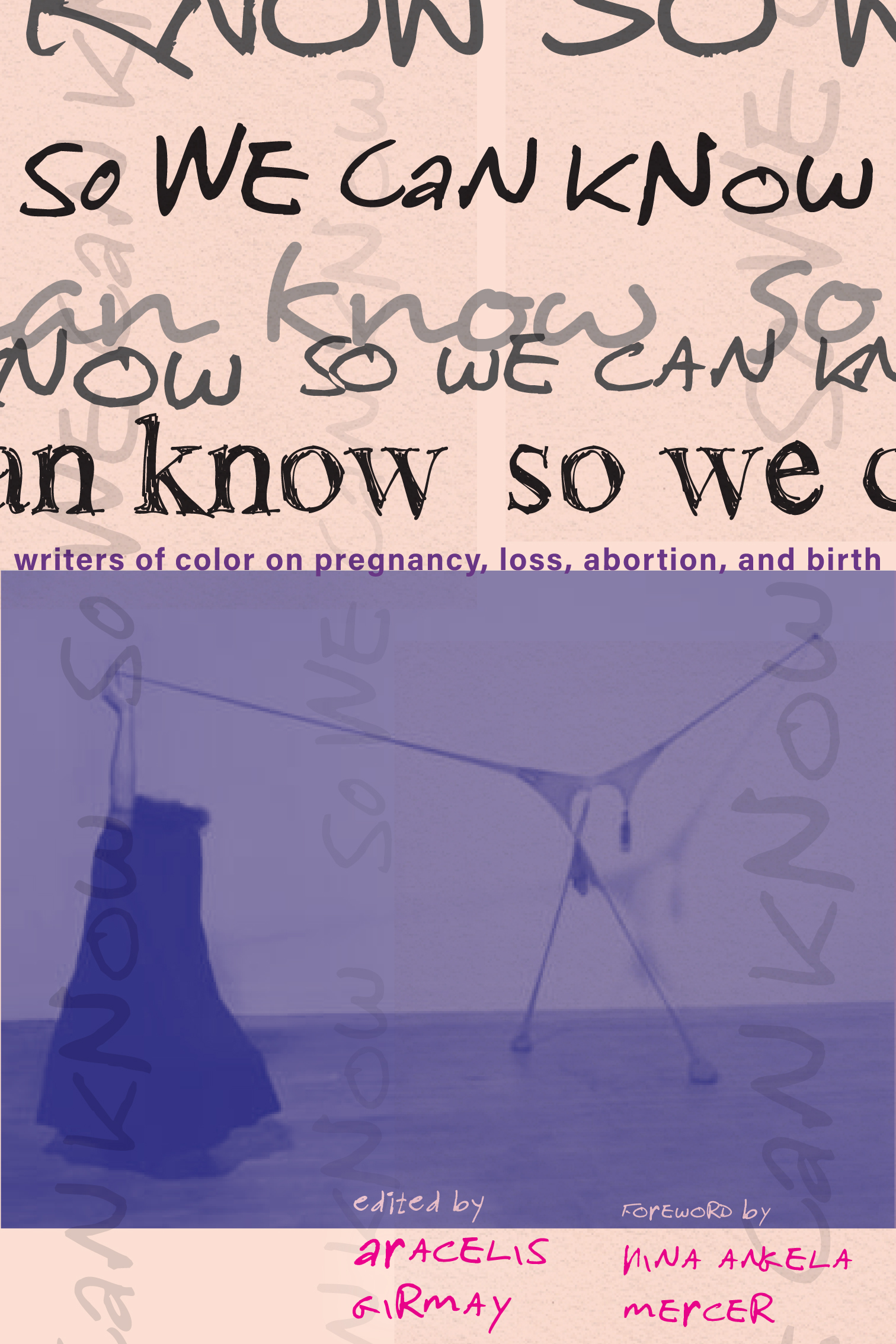

From So We Can Know: Writers of Color on Pregnancy, Loss, Abortion, and Birth edited by Aracelis Girmay. Used with permission of Haymarket Books. Copyright © 2023 by Angie Cruz.