Near the end of 1993’s True Romance, that Quentin Tarantino-scripted echt-1990s gumbo of trash-film lore and pop culture nerdom tarted up with perfume-ad Tony Scott direction and just-cameoing A-list stars, the comic-store-clerk-turned-gunslinger-on-the-run Clarence (Christian Slater) meets with Hollywood producer Lee (Saul Rubinek) to finalize a drug deal. Immediately, Clarence launches into a diatribe about what cinema means to him.

What does Clarence not like? Merchant Ivory award films. “Safe, geriatric, coffee table dog shit.” What does he like? “Mad Max, that’s a movie. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, that’s a movie. Rio Bravo, that’s a movie.” Lee—who just so happens to have made a Vietnam war flick which Clarence reveres—tips his cap to the young enthusiast: “We park our cars in the same garage.”

Given that Tarantino has called the script of True Romance his most autobiographical, Clarence can be read as his stand-in. Clarence also embodies the cinematic fan culture then coalescing. Within a few years, his dogmatic rage-screeding would become the coin of the realm, as sites like Ain’t It Cool News churned out the kinds of caps-lock manifestos that Clarence-ian enthusiasts could only dream of delivering to a producer’s face.

Much of the hype around some of the specific breed of ‘90s indie filmmakers—Tarantino, Kevin Smith, Robert Rodriguez, et al—centered on their dedication not to the high art of cinema but to the disrespected lower tranche of movies. A young Turk like Tarantino was more apt to cite Sonny Chiba, Silver Surfer, or women-in-prison exploitation flicks than Ozu, Ford, or Welles, preferring what Pauline Kael (whose writing enthralled a young Tarantino) called “a tawdry, corrupt art for a tawdry, corrupt world.” Like with each new generation of movie brats looking to upset the old order, this attitude seemed somewhat revolutionary at the time.

Three decades later, the revolution is over, though not necessarily won. Merchant Ivory are no more, their fans at home re-binging Poldark and Downton Abbey. The remaining arthouses show alt-horror fare more than the costume dramas or bloated prestige epics that Clarence despised. These days, overkill homages to Euro-exploitationers, like Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds, can hoover up Oscars. The fans are still fighting online, but now about things like diverse casting in comic-book films. As for Tarantino, he remains a fan of a very specific breed of film. What is more, he is turning that appreciation into a sideline career as an author.

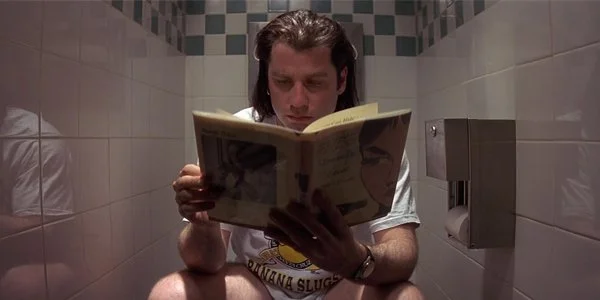

His first book was 2021’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, based on his 2019 film. Released as a mass market paperback and printed on appropriately dubious paper stock, it was made to look like the kind of quick-and-dirty film novelizations that once composed a profitable though semi-disreputable pillar of publishing, complete with back-of-the-book ads. The book is less a novelization than a remix, a self-produced work of fan fiction, or an expansion pack for the Tarantino Cinematic Universe.

His first book was 2021’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, based on his 2019 film. Released as a mass market paperback and printed on appropriately dubious paper stock, it was made to look like the kind of quick-and-dirty film novelizations that once composed a profitable though semi-disreputable pillar of publishing, complete with back-of-the-book ads. The book is less a novelization than a remix, a self-produced work of fan fiction, or an expansion pack for the Tarantino Cinematic Universe.

Filled with backstory, interstitials, and inner monologues, Once Upon a Time the book expands and riffs on its source material. The film is a loose, wide-ranging fairy tale about the movie business, circa 1969, told with a fabulist sheen and iconoclastic end-of-an-era attitude. Tarantino focuses on the dinosaurs still heaving around after the meteor has hit, trying to figure out the new landscape and maybe stomp a few hippies for good measure.

Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) is an insecure, alcoholic former movie star now relegated to heavy-of-the-week TV roles. He agonizes over the perceived indignity of turning to spaghetti Westerns. Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) is Rick’s stuntman, driver, handyman, drinking buddy, and shoulder to cry on; he also just so happens to be a war hero who got away with murdering his wife. Though the story is largely a two-hander, a third lane is carved out for the real-life Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), a bright-eyed blonde dream who lives next door to Rick and—in Tarantino’s alternate universe—is ultimately saved from the Manson Family by him and Cliff.

The book version of Once Upon a Time gets into the heads of Rick and Cliff as they knock around Hollywood. It doesn’t always work. Though Tarantino’s onscreen dialogue is delivered with riveting conviction no matter how baroquely written, in the novel it reads as inert, stagey, and inauthentic. Sometimes the dialogue takes the form of an interior screed of uncertain purpose. In one, Cliff, otherwise presented as a beer-drinking trailer-dweller, also turns out to be a fan of foreign films like La Strada. After a digression into the subjective morality of non-Hollywood filmmakers (“They didn’t care if you liked the lead characters or not. And Cliff found that intriguing”), Cliff has a Clarence-esque moment of his own:

He wasn’t buffaloed by them either. They still (one way or another) had to work as a movie, or what was the point? Cliff didn’t know enough to write critical pieces for Films in Review, but he knew enough to know Hiroshima Mon Amour was a piece of crap. He knew enough to know Antonioni was a fraud.

Cliff’s unprovoked dissertation might be more believable if he delivered opinions antithetical to Tarantino’s own great unification theory of cinema. (Perhaps praising Last Year at Marienbad over Yojimbo?) Tarantino is looser as a writer than filmmaker, wandering down plotlines from the film, fleshing out characters, and shuffling the story in a more non-linear way. Once Upon a Time comes across as something of a lark, a literary director’s cut, if you will.

Tarantino’s next book, 2022’s Cinema Speculation, takes a completely different approach. A silver-screen bildungsroman crossed with idiosyncratic film history, Cinema Speculation is the story of Tarantino’s youth, mediated through the movies he saw with his mother and her second husband (or her boyfriends) in the early 1970s. His writing—sharp, clear, slashing—makes the fictional stories in Once Upon a Time seem even flatter.

Tarantino’s next book, 2022’s Cinema Speculation, takes a completely different approach. A silver-screen bildungsroman crossed with idiosyncratic film history, Cinema Speculation is the story of Tarantino’s youth, mediated through the movies he saw with his mother and her second husband (or her boyfriends) in the early 1970s. His writing—sharp, clear, slashing—makes the fictional stories in Once Upon a Time seem even flatter.

Cinema Speculation surveys a dozen or so films, ranging from the acclaimed (Taxi Driver) to the forgotten (Rolling Thunder), to conjure a cultural experience that has largely disappeared: the double feature. The nature of the double feature meant people often saw the A- or B-list films along with below-the-margin fare. Unsurprisingly, Tarantino declaims in sometimes purple and sometimes quite insightful language about both kinds of films with a proselytizing eagerness. Like some of his more grandiose cinematic output from Kill Bill and after, the result is as exhilarating as it is exhausting.

What separates Cinema Speculation from Tarantino’s films is the personal stamp. He brings to the page that same intensity and swagger he used as a grade-school film buff telling other kids about the adult films he was taken to. (“I saw a lot of intense shit,” he writes.) He also attempts to create an origin story for himself as an artist. Taken out by a guy trying to curry favor with his mom, Tarantino saw the blaxploitation film Black Gunn in an “extremely excited audience of about eight hundred and fifty black folks” as a nine-year-old thrilled to be given license to shout at the screen and take part in a community experience:

I’ve never been the same … I’ve spent my entire life since both attending movies and making them, trying to re-create the experience of watching a brand-new Jim Brown film, on a Saturday night, in a black cinema in 1972.

Tarantino has built a career around that strain of fandom and now wants to acknowledge it more fully. His novel of Once Upon a Time is a paean to the Hollywood that created the films that formed him. His full-spectrum dedication to the medium is well-illustrated in Cinema Speculation, which pivots from Bogdanovich-esque name-dropping (John Milius told him this, Walter Hill said that) to spatting with or praising his local critics (Los Angeles Times A-list reviewer Kenneth Turan bad, Los Angeles Times forager of quality B-list fare Kevin Thomas good) and giving notes on how he thinks certain films could have been improved.

Given that Tarantino calls himself “someone who equates transgression with art,” it’s unsurprising when he gripes about a movie having pulled its punches. He complains, for instance, that Paul Schrader and Martin Scorsese weakened Taxi Driver by soft-pedaling the racial subtext (specifically casting Harvey Keitel as what Tarantino mocks as the mythical “Great White Pimp”).

The book’s most rewarding sections unearth forgotten material. Tarantino’s writing on John G. Avildsen’s Joe (1970), a bracingly weird and vicious film about a rich businessman (Dennis Patrick) hunting for his wastrel hippie daughter (a pre-Rocky Horror Picture Show Susan Sarandon) with a garrulous and gun-toting right-wing barstool philosopher (Peter Boyle), sharply explores a film whose anxieties and satire predated (by a year) All in the Family. There are overlong but buzzy chapters championing John Flynn’s Rolling Thunder (1977), a loopy Schrader-scripted actioner about a traumatized and hook-handed Vietnam POW (William Devane) who goes on a vengeance spree after losing his family to some desperadoes, and Paradise Alley (1978), Sylvester Stallone’s gonzo epic update of mid-century Warner Bros. street kid flicks that was also Tom Waits’s film debut.

With its conversational, be-bopping style, Cinema Speculation can feel like hanging out with a learned and fun but extremely long-winded film buff. There are sizzling hot takes (Francois Truffaut is overrated, Brian De Palma would have done a better job with Taxi Driver than Scorsese, the “anti-establishment auteurs” like Robert Altman and Hal Ashby were too solipsistic to make good work) and sharp insights (learned exegesis on the post-Death Wish “revengeamatic” films, asking rhetorically “does anybody really think Altman watched other people’s movies?”). But the manic style has its downsides, with numerous lengthy tears that are difficult to justify (just a bit less on Devane, please).

In both Once Upon a Time and Cinema Speculation, Tarantino is still to some degree the Kael-quoting video-store clerk who wants to ensure the gems of the past are not forgotten. But his manner now is a bit less Clarence and more Leonard Maltin. When he asks plaintively, “Am I the only one who remembers Barry Brown?”, referring to the star of Bogdanovich’s Daisy Miller, Tarantino knows the answer is yes and seems okay with that.

Still, his fandom is not encased in amber. It is a living thing. Tarantino’s books about the films and filmmaking of the past function less as museum exhibits than guides to keeping the form potent, relevant, and maybe still able to inspire another nine-year-old budding cineaste whose mind gets blown by a movie he never should have been allowed to see.