In this quarterly column for The Millions, I’ll feature the best new books of poetry. I’ve been writing for the site since 2012—interviews, essays, lists—but poetry is my true literary love. Specifically, recommending poetry. I’ve found that people who don’t love poetry haven’t yet found the right poem: that perfect mix of recognition and revelation. I’m drawn to poetry because it is mysterious, wild, prayerful, and surprising; truly, as Coleridge wrote, “the best words in the best order.”

For years, I’ve been writing poems—and writing about poetry. My next book, The Habit of Poetry, is a study of a minor midcentury literary renaissance: a group of nuns who wrote beautiful, challenging poems. Their work was prolific, moving, and yet largely forgotten: sadly, a useful analogy for the plight of poetry. I want to do a small part to change that. I hope that this column will reveal that poetry is very much alive—and flourishing.

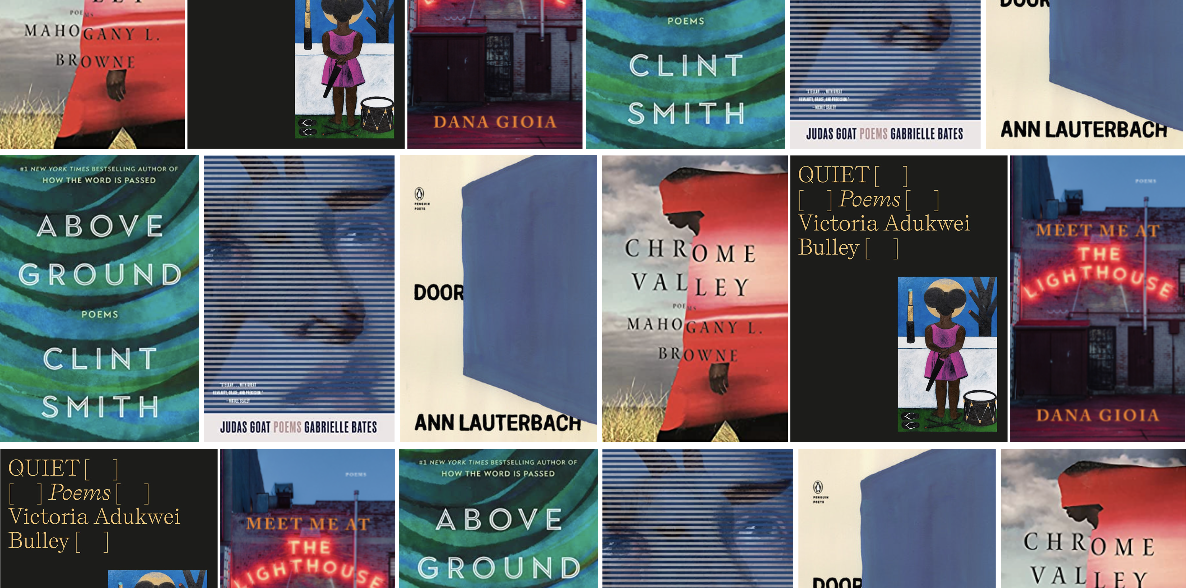

Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley

A Ghanaian poet interested in formal and syntactic experimentation, from poems that splash across the page to densely packed prose poems, Bulley’s work in Quiet is united by an examination of identity and colonization. Her poems are to be seen.

Bulley’s debut begins with the aptly titled “Declaration”: “if sickness begins in the gut, if // I live in the belly of the beast, if // here at the heart of empire,” then, the narrator concludes, “let me beget sickness in its gut.” The short poem’s recursive lines overturn and shift “empire,” “host,” “beast,” and “gut,” as if Bulley is affirming her poetic power to renew language a meaning. Her syntactic play is impressive, and her more traditionally lineated pieces are equally arresting, as with “Fifteen,” the narrator’s story of an early love. She wonders if a ten-year-old poem for a “blue boy” is, years later, “still a pining, asking // how many more I’ll make / having learned, at last, // how little of us keeps.” And the melancholy yet gorgeous “There You Are,” a meditation on a woman “boiling water on the stove / pouring the herbs into the pot” while she watches “them, holding / your heart in your hands at the table.” And though Bulley’s sentences often span across lines, she occasionally offers a terse exhale: “How hard, how heavy this all is.”

Judas Goat by Gabrielle Bates

Judas Goat by Gabrielle Bates

I’ve written elsewhere that the border between the sacred and the profane is porous, but Bates’s debut makes me wonder if such a border even exists. Judas Goat is a deliciously (perhaps devilishly) original book—a hypnotic, rowdy route.

In one early poem, the narrator writes of her childhood in a city, where “my father woke me with a hair dryer / under the covers; sheets lofted like a lung.” That deft, inventive image invites more play, as when she writes of being “raised at night,” how she would “Follow the red glow of brake lights from windowpane // to ceiling, out the door, over roofs until roofs grow rare, / fear the unborn eyes of cows, keep the hand flat / and a crabapple square in the middle—mouth into palm.” Bates quickly and precisely sets the place of her poems, as in the opening stanzas of “Dear Birmingham”: “I’ve been visiting again / the cemetery / with a sunken southern corner. // Fish smaller than first teeth, birthed from the soil, / maneuver in the glaze / where rain pools, covering the lowest stones.” Elsewhere, as in the potent “Sabbath,” Bates’s poetic control enables her to mine challenging themes of love and doubt, and how they are often united through longing: “Round white mushrooms emerge in clusters overnight, / soil scattered across their brows / like Catholics bearing ash. It’s taken me // almost a decade to admit it. I miss.” Other poems are razor-sharp, like the columnar “Ice,” which compels the reader to consider a doe: “What’s wild / will never / lie to you / if caught / like this.”

February

Chrome Valley by Mahogany L. Browne

Chrome Valley by Mahogany L. Browne

Just shy of 150 pages, the first thing a reader notices about Browne’s tenth volume is that it is generous and expansive—a decidedly full work. Across her poems, Browne deftly creates atmosphere through juxtaposition and pacing.

In “Best Time III,” a narrator recalls a scene from her teenage years, in the girls’ locker room. The poem unfolds through collective narration, as the girls remember “the last time we saw Deon alive / sideline smack-talker with unwelcoming eyes / boa constrictor of a boy.” In a folkloric voice, the narrator observes that “he took a girl’s stuff even after she pushed him away”—as a shared recognition among the young women rises as “all our girl bodies hold up the steam crusted walls.” Browne considers intimacy throughout Chrome Valley—bodies taken advantage of, young and unsure love, the love of parents, the power of longing: “it is only a Saturday / and church is congregating with each breath / your lover sleeps like a sermon like a body that worships only / one name” (“Little Deaths”). Her narrators, though, often feel unsatisfied with men—as in the prose poem, “A Chorus of Hands.” The speaker is on a dance floor in San Francisco “after I left my high school sweetheart in search of myself.” She writes, ironically, of what consumes her: “forgetting about the man that asked me to choose him over poetry. Forgetting about the man that only had rough hands to father me. A trick he learned from his father. A trick my grandfather learned from his country.”

Meet Me at the Lighthouse by Dana Gioia

Meet Me at the Lighthouse by Dana Gioia

In a 1992 interview published in Verse, Gioia recalled the “working-class Los Angeles of my childhood, which was quite old-fashioned, very European, and deeply Catholic.” He then corrects himself: “No, ‘European’ is the wrong word. Very Latin. The Sicilians blended very easily into the existing Mexican culture.” Among other merits, Meet Me at the Lighthouse, the latest from the former California poet laureate, is the first to fully examine his Mexican heritage.

The book features “The Ballad of Jesús Ortiz,” a narrative about Gioia’s great-grandfather—a vaquero shot dead in a Wyoming tavern. Ortiz’s story begins in Montana, and then the cattle drives where “days were hot and toilsome,” and “It wasn’t hard to sleep on the ground / When you’ve never had a bed.” More than a decade later, Ortiz found himself in a Wyoming tavern, tending bar—where he met his end: “The tales of Western heroes / Show duels in the noonday sun, / But darkness and deception / Is how most killing is done.” Other gems from this book: “Tinsel, Frankincense, and Fir,” my new favorite melancholy Christmas poem, which ends with this perfect line: “No holiday is holy without ghosts.” And his series of psalms for Los Angeles: “Let us praise the marriages and matings that created us. / Desire, swifter than democracy, merging the races— / Spanish, Aztec, African, and Anglo— / Forbidden matches made holy by children.”

March

Door by Ann Lauterbach

Door by Ann Lauterbach

Lauterbach’s eleventh book continues her investigation into art and culture, while focused on the theme and metaphor of doors. The book encapsulates a wonderful line of hers from a past interview: “In order to endure the loss, and not to let it utterly overwhelm you and utterly take you away from the life, you have to find some way to let it be the thing that animates your attachment to things, and the animated attachment is the present. It’s molecular—it’s just a piece of the life.”

A door is both the door itself (which opens and closes) and the space of the door (which is opened and closed), a metaphorical tension that Lauterbach imbues throughout her collection. “Hand (Giotto)” demonstrates her dance of punctuation: “A hand is waving, silently, from under / cover of cloud we said was blanketing / / the sky, and so, indeed, the sky is blank / but for a reverie of reach and touch; // the ancient, figured dark.” In the following stanzas, the narrator meanders through her misunderstandings—reaching for the word “fungible,” but ultimately needing to “trade it for // another,” a word that “means a shadow can pass through // unnoticed.” The sense permeates Door in poems that arrive with Lauterbach’s conversationally philosophical tone. She later writes: “Let’s explore what words cannot.” This book does just that, masterfully.

Above Ground by Clint Smith

Above Ground by Clint Smith

A gorgeous book. The second volume of poems from the author of the celebrated nonfiction bestseller How the Word is Passed. Smith’s pivots and pacing mirror the routes of our lives, and his gentle, attentive poems are downright sacramental.

I’m especially drawn to the poems where Smith is a father, fielding questions at bedtime (it is always bedtime that prompts the most philosophical concerns) about poetry and life, or writing an ode to the double stroller (“You are the monarch of suburban pavement, / a double helix unbound and unbothered, / a map unfurling itself across the table / and pushing everything else onto the floor.”). Children make for good poems because they are us—unfiltered, new, steeped in wonder and weirdness. Yet Above Ground is also anchored in loss, as in a poem where a narrator envies a small jellyfish that is the only creature that can “regenerate its cells and go back / to the beginning of its life cycle.” The narrator wishes the same for his grandfather, “his blue veins growing / thick down the side of his legs, the ear he can no longer / hear out of, the way his hands shake and his spoon quivers / and his soup spills onto the table.” The narrator is angry: “My grandfather is eroding away and science tells me / I must accept it. What need does a jellyfish have / for an infinity that will only get lost in the current?” I love poems that end with question marks, and I appreciate poets like Smith who turn the page between hope and loss, fear and exuberance.