Not so long ago, in the days when things were unraveling quickly in the Soviet Union, foreign commercial flights were prohibited from landing in Moscow during daylight hours. Prying eyes or something.

Still, on my first flight into the city, I held out hope of catching a bird’s-eye view of the outrageous architectural assemblage of the place. Bands of cookie-cutter high-rises housing 10,000,000 Muscovites (though who could know for sure?) ringing the center peppered with Stalin’s pharaonic towers, floodlit monuments to grasping, jutting socialist realism and block after block of the flatus of late Russian Empire excess. From 30,000 feet it would be mirabile visu. Even at night.

And there was this: with the Soviet experiment in ruins part of me was curious to learn whether chaos was visible from five miles up.

What I didn’t know was that Sheremetyevo Airport was located well outside the city—an hour’s drive through forest before you reach anything resembling civilization. Flying into the arrhythmic heart of Soviet Socialism was a flight into the void. Still, I spent the final 20 minutes on approach in vain, my nose to my SwissAir cabin porthole searching for any sign of the biggest city in Europe, while my suspicion turned to certainty that to land in Moscow was to land in the dark.

Which it was. I arrived in Moscow having seen nothing out the window but the runway lights. I spent my time in the passport queue reconciling with what would be the first of many Russian jokes to which my existence was, apparently, the punchline. And then I went off to find a taxi, determined to see the city. $40 later, a chatty Armenian cabbie was bypassing my hotel and taking me and my hard currency to Red Square where he pulled off the road and parked about halfway up the slope below St. Basil’s Cathedral. It was past midnight and snowing hard. I sat for a moment, gauging the probability that the driver would leave me there if I got out and walked up to the church, and weighing that against the amount it would add to his tip if I opened my mouth and offended him by asking him to wait. “Five minutes. Ten,” I said. He winked and I climbed out of the Lada.

I walked through the snow toward St. Basil’s with its impossible technicolor cupolaed profile, big flakes coming down, just enough light from street lamps and just enough sweep to the wind—an homage to classic Soviet cinematography. Up near the barricades erected around Red Square stood this kid in his army great coat and shapka, on guard. I walked up to him and asked if I could just look for a minute or two. Afterward, I fished a hardpack of Marlboro Reds out of my coat pocket and offered the boy one and we lit up and stood and smoked Virginia tobacco there in the falling Moscow snow. He was 19 going on 90 and I was 30 going on nine.

In a week it will be nine months since Russian missiles began targeting Kyiv. Eight months since we fled our home for Poland, Czechia, Scotland. It is safe where we are now but our world, the loci of our mundane has been shredded and reconstituted as clickbait, providing sustenance for war fetishists and fodder for the nightly news. To hell with them all.

The soldier and I have corresponded regularly for nearly the entire three decades since we met and shared a smoke. My address changing, his not. At some point late last year his letters stopped, and I have thought a lot about that. He would be 50 now. If he hasn’t yet been mobilized to the front in Ukraine, I want to hope that the reason he stopped writing is that he resisted. Tore up the conscription papers when they came, headed out to his dacha, planted his potatoes, and sat with his shirt off in the late summer sun. That he is at peace and refuses to feed the beast.

*

This has been a year of discrete blessings for my family, one in which I have learned the value of a contingent existence. It took 60 years, but I have, at last, taken the ancient admonition to heart and considered the lilies of the field, arriving at the understanding that I understand nothing. I cannot know what tomorrow holds and there is solace in that.

That sense of solace colors all the books I am compelled to recommend this year. Read in the spirit in which they were written, these bring to mind the old construct “in the fulness of time.” Of things meant to be. They comprise essays, stories, confessions, and anecdotes of beginnings and endings, of existence, resistance and renewal, of gain and loss, transition and transcendence, of setback and resolute engagement with the time afforded us.

Peace from Scotland

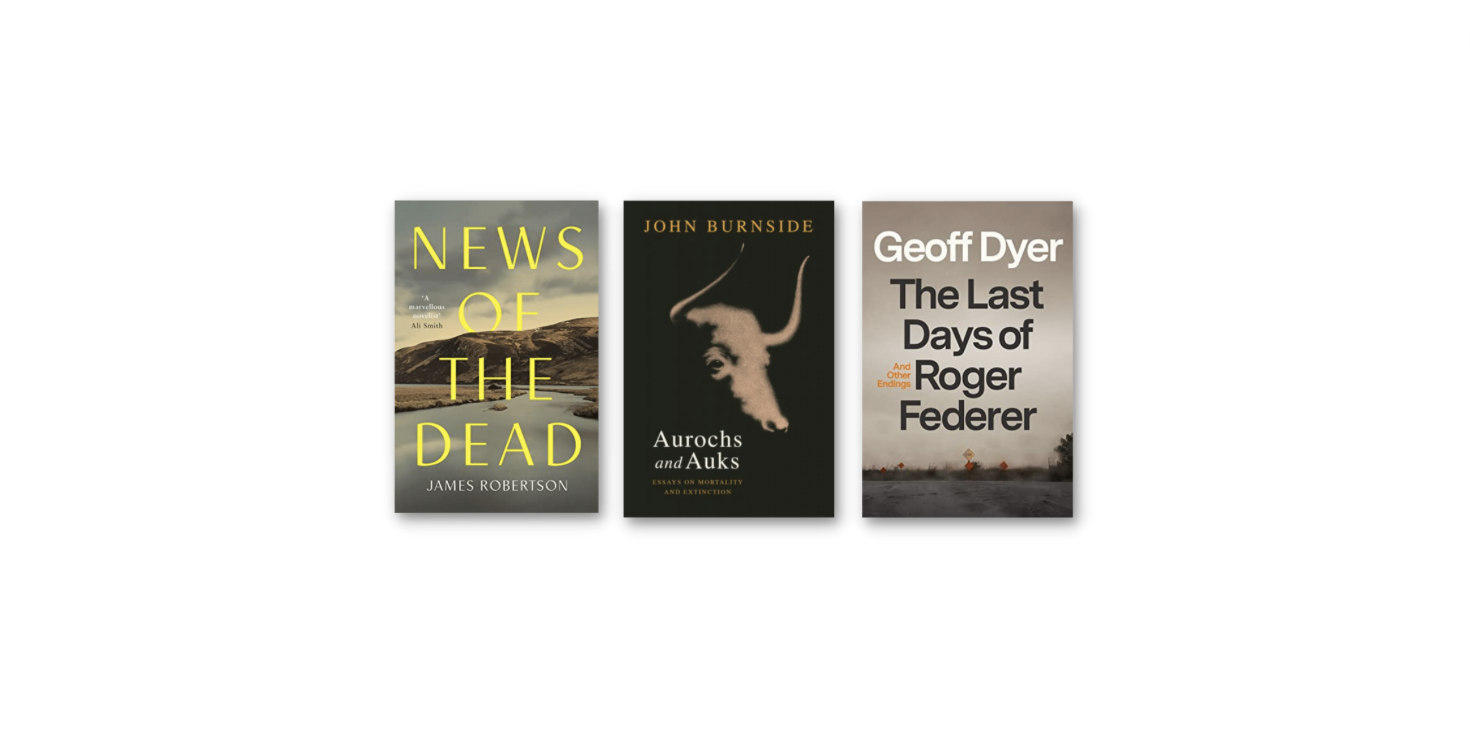

Aurochs and Auks: Essays on Mortality and Extinction by John Burnside

A masterful poet, here Burnside takes up his essay pen offering four pieces on the natural cycle of life, death and renewal. Beginning with an examination of the artistic reverence that resulted in the cave paintings at Lascaux and Nerja and closing with the telling of his own near demise in a Covid ward, he plots out the troubled continuum of our relationship to our natural environment and offers practical approaches to the revival of a reverent stewardship of the planet. This is no environmentalist screed but an appeal, an encouragement, arising from an ache for life.

News of the Dead by James Robertson

News of the Dead by James Robertson

Robertson conjures up a tale of three lives separated by centuries but joined by their common connection to the settlement of Glen Conach in the northeast of Scotland. Deeply engaging historical fiction on the essential nature of myths and legends handed down to us in the defining of our own sense of self and community. A rare piece of writing.

The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings by Geoff Dyer

The Last Days of Roger Federer and Other Endings by Geoff Dyer

A series of reflections of varying length—some approaching formal essay wordcounts, others sputtering out after a few paragraphs—on “things coming to an end, artists’ last works, time running out.” Which might sound a bit depressing but isn’t, even a little. The title is intentionally misleading, I suppose. This is hardly a book about tennis or at least as much about tennis as it is about, say, Nietzsche, Bob Dylan, and Louise Glück.

The Passenger and Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy

The Passenger and Stella Maris by Cormac McCarthy

It’s been 16 years since The Road and I don’t know what I was expecting when it was announced that these would be released as companion novels, but it wasn’t this. McCarthy has somehow managed to entirely dismiss while fully embracing everything he’s ever written before this. And yet, for their singular chronology, their irreverence, and their thematic complexity, I’m not taking any risks by insisting that this is his best work yet. One proviso: you have to read both books. In sequence. Limit yourself to one or the other and all bets are off. The structure falls. Eighty-nine years old and still toying with us.