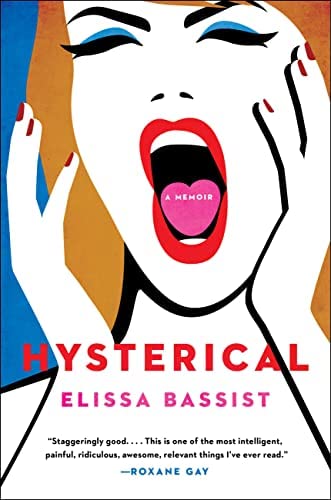

Having read her feminist memoir, Hysterical, it’s easy to imagine Elissa Bassist, a la Arya Stark, sharpening her pen and reciting the names of all the men who’ve wronged her.

There’s the on-again, off-again boyfriend/fiancé/nemesis—dubbed Fucktaco—who sporadically ghosted her over a tortured decade. The bosses who berated and belittled her. And the parade of doctors who tuned her out, downplaying her suffering, then prescribing drugs that compounded the pain until it throttled every part of her body.

That may not sound like fodder for comedy, but Bassist is a brilliant humorist who knows how to balance weight with wit. She describes an antidepressant as “an SSRI, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, if you’re nasty.” Envisioning losing her virginity as an adolescent, she swoons, “We’d do things to each other we couldn’t spell, and he’d whisper Pablo Neruda into my vagina.” With a voice so distinct, it’s no wonder her silence almost killed her.

We spoke via video-chat while Bassist, on her book tour, was getting settled in a Los Angeles hotel room.

(This interview has been lightly stylized like a medical questionnaire.)

Evan Allgood: Are you feeling healthy and well today?

Elissa Bassist: (laughs) Yes.

EA: Why did you laugh?

EB: (laughs more) I’m feeling healthy and well today. Physically.

EA: Are you feeling stressed mentally?

EB: Yes. I’m in a new place. It’s a place that requires you to wear shorts, and I’m anti-shorts. I didn’t know how to pack for this trip because I don’t have any of the required L.A. couture. I don’t own a pair of shorts.

EA: So you’re feeling physically healthy, mentally unwell due to having to wear shorts.

EB: Yes. I also got my first piece of hate mail about the book, from a woman who suggested that my problems had nothing to do with culture and everything to do with nurturing. In an incredible display of growth, I deleted the email. If I were even healthier than that, I would not have read it. But I’m still extremely proud of myself that I read it one time only. It’s great that I don’t really remember what it was. It was something about how my parents didn’t love me enough. I couldn’t agree more.

EA: Do you have any family history of your parents reading your book?

EB: My mom read it and loved it and felt that it was a tour de force, even if she didn’t use that phrase. It was difficult for her to read. She couldn’t read it before bed. She thought it was both darker than I had prepared her for and not as bad. My dad finally read it—he said he liked the second half better. The first half he was a little bored.

EA: The first half is when you almost die! How did you decide to structure it this way, with the medical issues up front?

EB: I think that was the number one problem with the book—figuring out how to structure it. I don’t know anything about structure. I’m incredible at writing all my feelings down… and that’s it. I was told that I had to organize these feelings in a way that was propulsive and contributed to something called the “narrative arc,” which I still am unable to define. I wrote down “narrative arc” for a Catapult class that I’m going to be teaching, called How to Write a Tragicomic Memoir, and it’s just blank. I don’t know what that is yet. (laughs)

Anyway, I had to do something called the narrative arc, and the only way I cracked the structure was by writing hundreds of book proposals and having hundreds of agents reject them and give me notes on how to order the book. Then my editor, once I got her, we kept going back and forth. It took so many tries, and experimenting with doing it one way, then another way, then another way, and rewriting the book multiple times to see what worked. It was like putting together a puzzle as you’re creating it, and feeling like there’s a right way but there isn’t. I remember in the later drafts, when the book was past deadline, I would have these epiphanies that were related to plot and narrative arc, where I realized, “Oh, this is a good way to end this chapter that leads into the next chapter.” I felt like a genius. Obviously I figured it out and I did a great job.

EA: Have you noticed a significant difference in the way male doctors diagnose and treat you versus non-male doctors?

EB: I would say it felt more like a systemic problem than a gender problem. There was not much difference between doctors who are men and doctors who are women. There just so happened to be exceptional doctors, and they were all women. The ones who listened to me, believed me, understood where I was coming from, could have a real and substantial and lengthy conversation with me. But it was shocking how sexist many of the female doctors were.

When you’re at the doctor, you’re trusting these people who have all the knowledge in the world, and you’re in the most vulnerable position in your life because you’re in pain, you need help, you don’t know what’s going on, and they have a 100 percent of the power over you. Especially when you think or hope that they have the solution to your problem, you’re more willing to blindly do whatever they say, because they know better than you do. That’s how I got into every problem with medication, was just assuming that they knew more, I knew nothing. I was desperate for help. I was willing to do anything to end the pain that I was in, and they offered a solution, so I’d take it.

EA: Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems?

- Men explaining your book to you: I wish this had happened just for this story, but it hasn’t happened yet. I will say that after a reading in Denver, when I read the “Crazy Psycho Bitches” chapter of the book, where I talk about how any conversation can become a diagnosis if a woman says, thinks, or feels anything—a man came up to me after the reading and said, “I think you have autism.” (laughs) I was like, “Is this a bit?” And he said, “No. I think you’re on the spectrum.”

- Men calling you a liar: Not in this iteration of the book, but I have been called a liar by my previous bosses. The main thing they all had in common, other than being narcissists, is thinking I was a liar. We’re a nation of liars, but women are the only ones who get in trouble for it, and we’re often called liars when we’re not lying. It’s usually when we’re telling the truth. People just don’t want to believe what we’re saying because they don’t want to believe that people are that bad, or that pain could be that severe. It comes from a place of deep denial, that someone could be telling the truth about something that they don’t want to be true. I feel like when someone calls you a liar, that’s more a reflection on them than you.

- Men calling you hysterical: Only in reference to how hilarious I am.

EA: Over the past two weeks, how often have you been buoyed by the following joys?

- Listening to Taylor Swift: Every day of my life. I’m listening to Taylor Swift right now.

- Watching your dog doze next to you on a plane: Well, he was under my feet. But that did not give me joy because he is very upset. He was stuck in his carrier for four hours. But it gives me joy seeing him run and play fetch outside. I’ve never seen a happier creature in my entire life than Benny Theodore Bassist running outside playing fetch. My mom in Colorado has this huge backyard, so I now feel guilty that I don’t live in a house. I think I have to move for him. I think he’s going to be depressed going back to New York.

- Remembering that you wrote like a motherfucker and wrote this motherfucking book: Twelve times.

EA: How should women deal with (gestures at everything) this?

EB: Don’t date men. Don’t work for men. Don’t talk to men. Create a new society without men.

EA: Over the past two weeks, have you silenced yourself?

EB: No. Today on the plane I was given the cookies, and I wanted the pretzels as well—I’d asked for two snacks—and I said, “Excuse me,” and the man next to me said, “Excuse us,” and I said to him, “No need. I got this.” I got the flight attendant’s attention and said, “May I also have pretzels?” And she said, “No. I only have a limited amount.” But then later she said, “Someone rejected their pretzels, you may now have these pretzels.” I got my pretzels and my cookies, and I was in my power the whole time. (fishes Biscoffs out of bag, proceeds to eat them)

EA: Over the past two weeks, have you said no to someone?

EB: Yes. In Denver my mom took me shopping, which is something I hate to do. A big part of why I don’t like shopping is I feel like I cannot hurt the salespeople’s feelings by not liking their clothes. So this time, the salesperson was bringing me all these clothes, and I just kept saying, “No. No. No.” I was saying no to everyone, with abandon, about all these clothes I didn’t want to wear. No, I don’t want to wear shorts. Callback.

It feels so good to say what you’re thinking, and it saves so much time. I feel like I wasted so much time apologizing and protecting people’s feelings and not getting what I wanted and pretending. Saying no feels great.

EA: Over the past two weeks, have you texted any of your exes?

EB: I texted Fucktaco to see if he’s read the book. He sent the most Fucktaco response, which is, “I can’t read it until Sunday.” He’s insinuating that he’s very busy and that he’s working on his own writing and that he just doesn’t have time until this designated day. And he took a picture of the book in the bookstore. I expressed excitement, and also did one brag, and then did an acknowledgment of how I found all the typos already.

EA: If you hadn’t told him that you’d already found all the typos, would he have pointed them out to you?

EB: Yeah.

EA: Seems like a really cool guy.

EB: (laughs) I loved him very much. It’s amazing that that entire book isn’t about Fucktaco. The chapter on Fucktaco originally was 10 times as long. My editor cut it to shreds. She said, “This relationship makes no sense. He’s evil and you’re stupid. I cannot stand him or you. This chapter needs to be 10 pages max or I won’t read it.” This is how I could be in love with Fucktaco for so long: because I was my most prolific, and that’s what I love.

EA: Over the past five years, which writers do you consider to be your biggest influences?

EB: Jo Ann Beard. Alice Munro. Maggie Nelson. Samantha Irby. Michelle Orange. Arundhati Roy. Elif Batuman. Lydia Davis.

EA: Over the next five years, when Hysterical is adapted into a movie or show, who should play you?

EB: Cristin Milioti, the mom from How I Met Your Mother. Or Timothée Chalamet.

EA: On a scale from one to 10, how well do you think Bill Murray understands rape culture?

EB: Two.

EA: That’s what I figured, having read in your book that he tried to carry you to his hotel room after you’d had “infinity drinks.”

EB: I’m changing my answer to one. A man gets a ten if he self-castrates in front of me.