Debra Di Blasi’s Birth of Eros begins appropriately enough with a birth: the cinematic, slapstick delivery of the novel’s narrator, Lucy, who tells us she remembers her arrival in all its gravity-defying detail. Mishandled by the doctor and then squirted into the air by an over-anxious nurse, she is sent “high, higher into the air, my umbilical cord trailing me still… my body rotating to a perfect vertical so that I must have resembled a levitating Christ child depicted in old Flemish paintings.” When Lucy lands safely on a pile of soft white towels, her mother looks over the edge of the bed, sees her newborn daughter swathed head to tail in “monkey-thick hair,” and declares, “’Oh, God, she’s so ugly!’”

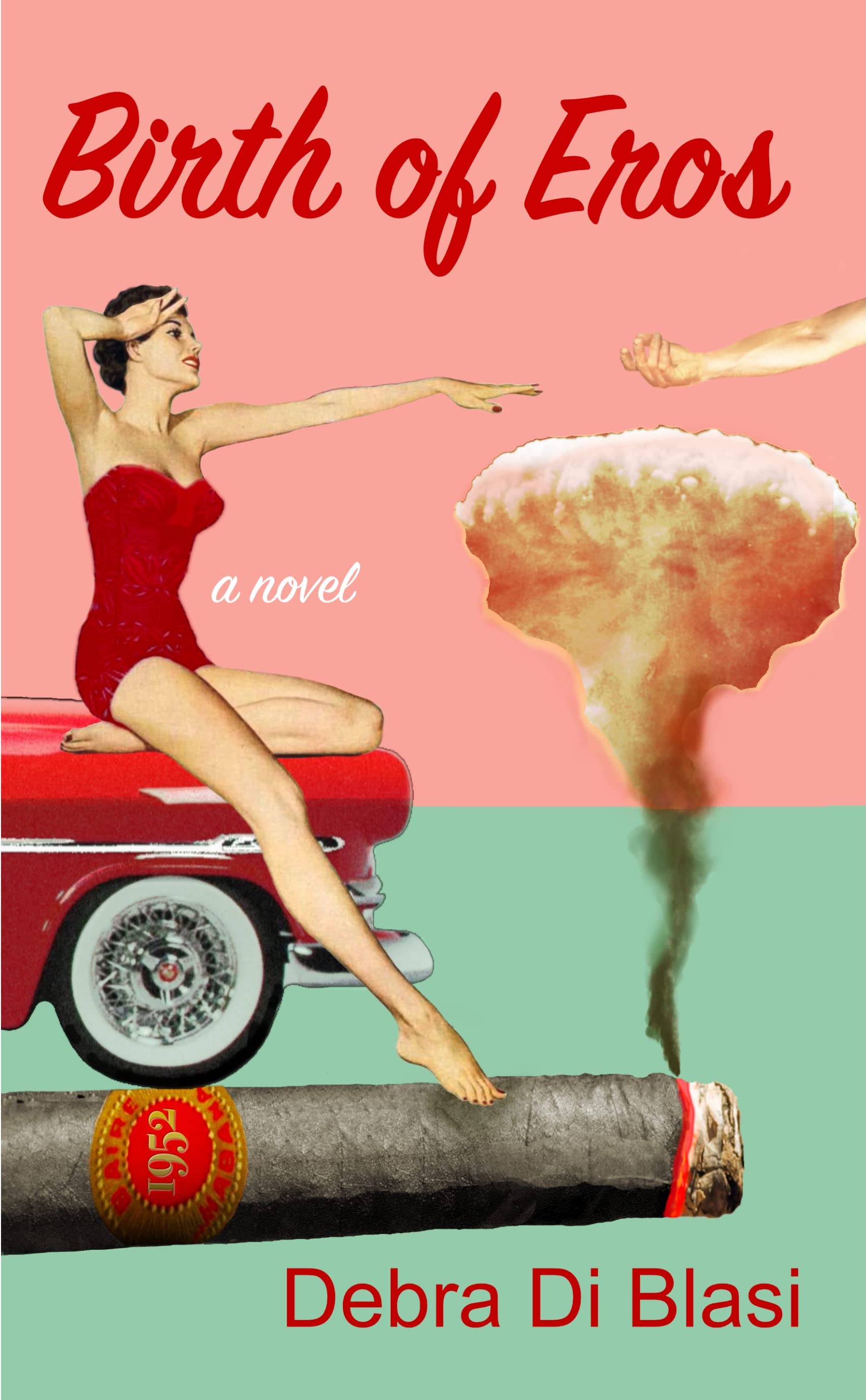

Lucy’s appearance is a surprise because her parents (referred to throughout the novel as “the mother” and “the father”) are paragons of 1950s beauty: she is “a dream, a girl machine, a living doll,” and he is a well-hung underwear model, the “too-handsome-for-words guy in the tightie-whities.” They are, as Lucy describes them, “Not smart. So not smart,” and, as a result, become the chattel of The Big Bad Wolf, owner of a large automobile dealership, possessor of microscopic genitalia and a cruel creepiness. Trapped in a byzantine contract, the father and mother pose like mannequins flanking shiny autos on a rotating tableau and woo buyers with their shared pulchritude. But this indenture is literally and metaphorically window dressing for the humiliation Wolf inflicts on the pair. After the vile car salesman’s unspeakable violation of Lucy’s mother, they “put their heads together to make one smart cookie,” and plan their revenge.

Lucy’s recounting of these events, and those that occur before her birth, have the ring of authenticity if we believe her claim that she was born with the gift of an omniscopic right eye (“vision broad and deep as the eye of god whomever’s”) that endows her with a preternatural ability to see virtually everything. Her extraordinary vision is central to her—and our—understanding of post-WWII America. In that shell-shocked world, beauty equals fame which equals riches, and both of her parents buy into that promise. Their naïve pursuit of a better life, leaves them vulnerable to characters more worldly and unscrupulous. Thanks to her omniscopic sight, Lucy is able to recognize the danger her parents are in, but, as an infant, there’s little she can do but watch and report: “Three plus one equals misery. Especially if one is a motherfucking car dealing, money laundering pornmonger.” Though the arc of Lucy’s parents’ lives is reckless and calamitous, she feels no resentment for their poor decision-making. They were, after all, doomed from the start to be sacrifices to a society that was “[a] lie, a pie in the sky, American Dream all awry.”

Lucy’s omniscience extends beyond the story of her parents and of this particular moment in history. Seeing through time to humanity’s beginning, she sees the species as “so smug, barely a rung away from our chimp cousins” and asks if we are “satisfied with who we are, what we’ve become, to desire stasis over evolution?” The tale of the mother and the father are, on one level, a cautionary tale, a warning to stay vigilant in a society not far removed from our tree-dwelling ancestors, and, on another level, “an old improbable tale” from our “mythological past where gods and goddesses toyed with humans” dispassionately deciding our fate.

In fact, Di Blasi describes this book—and three other planned novels to be narrated by Lucy—as “mytho-lyric.” Using the Freudian instincts of Eros and Thanatos as underpinning, the tetralogy will explore “in part, the creation of destruction” from the end of World War II to the outbreak of the 1991 Gulf War. That 40-year span of time was a period of head-spinning change in human history when ideals and morality were twisted, reversed, abandoned and replaced by unrecognizable versions of their former selves.

In this first volume, Eros is embodied in the mother and the father, their shared beauty and sexuality, and their creation: Lucy. Lucy, who is simultaneously innocent and all-knowing, revels in her parents’ love—”Why , my yes! They were fine when they touched, and seeing made me laugh, and when I laughed I felt they were a good fathermother…Oh I loved them loving so much!” At the same time, she detects the presence of Thanatos (in the person of Wolf) and the promise of destruction inherent in a society driven by materialism: “Tell me the function of beauty beyond titillation, beyond the buy & sell, the trade & barter, the pimp & the whore.”

In this and the many other observations, we are reminded of Lucy’s supernatural sight and of Di Blasi’s skillful use of an exceptional storyteller. Theirs, we can hope and surmise, is a shared sensibility. The hypothesized fusion of narrator and author is best represented in a passage about a sense “wedged against seeing and smelling and hearing that relies on the spaces between. A sense thick as the scent of sex, as a lover’s cock or tongue, blood drying, that feeds the artist, writer, music-maker the impulse to make, create and recreate, replicate, duplicate, celebrate.”

The Birth of Eros is a delight, a complex, well-structured book, deft and surprising in its movement from scene to scene, idea to idea, image to image. But it is the writing itself that brings it to life. Di Blasi is a master stylist, and her sentences crackle. Whether it’s a short proclamation (“See, in falling I learned to see”) or a long description—

For one year after their first meeting, she and he stood side-by-side on the Sale-O-Rama stage in swimsuits scandalous, barely this side of frolicking on a phony beach next to a sports coupe big enough for two kids too, and handsome he tossing the beach ball too high so that beauty missed and stepped to the edge of the platform to retrieve the ball always from some poor Mr. Married lusting for beauty bent over him while ballsy handsome laughed gaily, giddy throat mirth, and shrugged tan muscled shoulders and used the moment to sign smuggled posters of he-in-his-undies damp with sweat and whatever-juice and everyone pretending not to see the eye-level meatwhistle behind the trunks.

—Di Blasi uses language tempered with a rollicking rhythm that propels the narrative forward but also pulls it up short when it’s the right thing to do. There are no wrong steps in this novel, no wrong words, no wrong twists or turns. The book is, as Lucy reminds us,

more compelling, more enticing than the preservation of soul.

Or a narrative improbable.

The nonsensical made sensible.

Sensible enough.

If Di Blasi holds true to her plan, more Lucy-told novels promise new insights into our recent past and, no doubt, into the future as well. Though it’s tempting to wish the whole saga were finished, it’s best to be patient and enjoy Birth of Eros, a tight little fist of a book, gut-punching the American Dream.