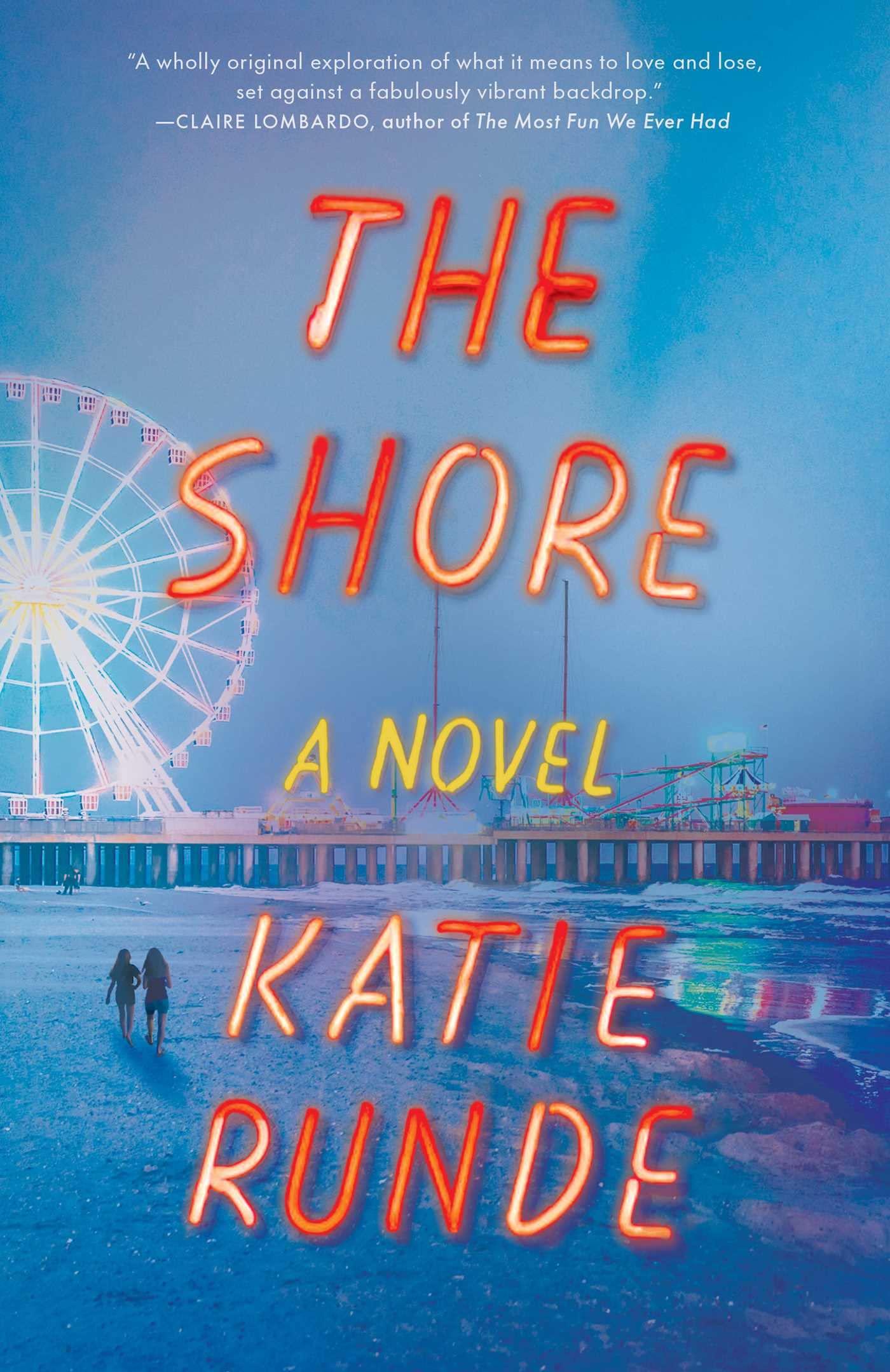

Katie Runde is a writer currently living in Iowa who grew up New Jersey, the setting of her debut novel The Shore. The novel does this wonderful trick of both giving the reader the full experience of a summer on the shore as told by those who live there year-round, while also telling a very difficult and poignant story about illness, family, marriage, sisterhood, and love. Katie and I corresponded over email about navigating loss, carrying grief, and making art from heartbreak.

Matthew Zanoni Müller: The Shore is told through multiple points of view, following sisters Evy and Liz, and their mother Margot, over the course of a summer in the town of Seaside after their father and husband Brian is diagnosed with Glioblastoma Multiforme, or GBM. These three women are so deeply and empathically rendered, and I wonder how you came to the decision to use their multiple points of view to tell the stories of their particular experiences. What kinds of opportunities did this open up to you as a storyteller and how did it affect the way you structured the plotting of this novel?

Katie Runde: An earlier draft of this book was only written from one point of view: 17-year-old Liz. But there were so many places where the rest of the family felt like they had more to say, where I wanted to know what they were up to when they weren’t with Liz! It was so clear that their grief, both from what they’d already lost to Brian’s GBM and were going to lose in a different way when he died, and their self-protective responses to it, were going to separate them, and we had to see them out in the world and alone and inventing new identities that gave them all a place to escape.

MZM: This novel makes great use of inter-textual elements. I’m thinking here especially of the GBM wives’ online discussion forum, which becomes so central to not only the novel’s tension, but also the ways in which we understand the characters in the book. I’m also thinking here of the use of old emails and the text messages that the girls send to their mother, their friends, and their love interests. What possibilities did giving the reader access to these posts, emails, and messages open up in the telling of this story?

KR: More than any part of the book, the GBM wives’ posts felt like they wrote themselves, like I was totally possessed and this voice that just needed an outlet was pouring out. I would bet a lot of people have made up a username and turned to one of these kinds of forums at some point—we go there when we have questions that Google or doctors or our loved ones can’t answer, and when we need to find someone out there going through this same, very specific thing that we’re going through. You can say things there that are vulnerable because it’s anonymous. In The Shore, there’s another layer of tension in the forum interactions, of sadness that these two characters are sometimes writing messages from the same house, but can’t say these things out loud to each other.

I also loved writing the old emails. I would give anything to have the old IMs and emails I sent in college and my early 20s, feeling so lonely and independent at the same time. I think finding relics and evidence of old versions of yourself, or someone you love and you’re losing, is such a comfort, a reminder that life is long, and there are so many versions of ourselves, and the one in the midst of this season of fresh loss won’t be the ones we are forever.

MZM: The GBM wives forum is just one of the many ways that you depict how illness affects this family: we see how Brian is changed by the diagnosis, how his family and friends must scramble to adapt, and how the process is shown in such clear detail throughout the arc of this novel. What was most important to you in rendering the experience of a family member’s illness in this story?

KR: Definitely the double-loss of caring for someone who is not himself. You lose him twice, first when he changes, and again when he actually dies. And for most of the illness, the caretaking is not at a bedside, but out in the world with this new, different person, arguing and chasing and feeling so vulnerable and confused and exhausted. And a GBM causes different changes, depending where it is in the brain, not necessarily to memory like someone struggling with dementia.

You absolutely must shut a part of yourself off to make it through caring for someone like this. And then when it’s over, it’s not so easy to just flip back on. You had to transform into a different, all-business, delayed-grief, patient, dark-humor-filled person to get through an hour or a day, years, and finding your way back to turn back on feeling everything is really hard.

MZM: One central tension in the novel is how each character must navigate the difficulty and heartbreak of Brian’s condition while also trying to still live a normal life: seeing friends, falling in love, going to work. Of course, each character manages this differently, and I’m wondering how you approached or thought about rendering the complexity of each characters’ management of this situation as you crafted this story?

KR: Just as our immune systems react to try to protect us, our alchemy of brain chemistry and our own experience goes into overdrive to protect us from pain, from overwhelm, from the unknown. For Margot, that also means trying to protect her girls as she’s imploding emotionally herself. I think more than managing, they’re reacting, and also compartmentalizing, definitely disassociating. In my experience, you have to do this in the acute worst-of-it time and we don’t have any more of a say in how we react than we do to how our body responds to a virus. Scenes with Margot and the girls communicating with each other were both the easiest things to write, in terms of what will these characters do when I throw this at them or put them in this room together. But it was the hardest because of the painful gap you have to create between what’s in their head and what they intend and how much they love each other, and what they’re actually saying and not saying. This is my favorite thing about reading fiction, versus watching a film: the constant negotiation of that space between what we intend and feel, and what we say.

MZM: Brian’s behavior, once his disease has progressed, represents an aberration of social and parenting norms in really stark ways, from running into traffic, to screaming obscenities at Margot and Evy and Liz, to dressing inappropriately. This separates them from their communities in a variety of ways, while also throwing into stark relief how their version of “normal” has been totally upended. This is clearly an inversion that places them in an alienated sphere all their own. I wonder how you have come to think about illness in this context, and what it might teach us about our society, the people in our lives, and of course ourselves? I’m thinking too, for example, of Margot’s need for connection with others who are in similar situations, as in the GBM wives’ forum, the need to inhabit a sort of kinship of grief. This also brings up our society’s relationship to illness, which often seems radically inadequate. What messages about illness are you hoping to send with this story?

KR: Margot has a few moments where she realizes the amount of emotional labor she will have to do to maintain her friendships through this, and she’s like, I know your hearts are all in the right places but I can’t show up and act normal and say I am fine at book club, but I also can’t show up and sob and talk about myself the whole time, so catch you later, keep me on the email list! There are also people who just get it, like Brian’s old friend Robbie who lets Brian “work” at the bar. He’s happy there, there’s access to some part of Brian that bypasses the personality changes at least for a few hours. We had a lot of family and friends like this in my real experience, and I leaned harder into the isolation for this fictional family. This family has a lot of privilege—health insurance, enough money and assets, excellent healthcare nearby, good hospice care when the time comes. But our culture insists on an almost superhuman kind of resilience.

I think we are finally having a conversation about the carrying of grief and how it changes over time, as opposed to the moving on from it. I actually think for all the awful aspects of social media, it has helped with this one thing. On Mother’s Day, there were so many beautiful posts talking about mothers that might have been gone a long time, but how the person thinks of her every day, right there on the grid or in their stories with whatever books or fashion or food their account is normally about. And I think that’s a beautiful thing to share as often as we can with as many people as we can.

MZM: Did you have a specific reader in mind for this novel? I can imagine this book as a love letter to coastal communities, as a source of comfort and recognition for those who have faced similar travails with an ill family member, and as odes to first love and the complexities of parenting.

KR: Yes, this is for anyone who sees a place they love and know portrayed in pop culture and wants to tell more of the story. It is for readers who love this complicated both/and space where humor and heartbreak and loss and beauty and memory all exist at once. I hope anyone who’s facing the loss of someone who is not themselves will find comfort in all the characters’ flaws and ways of coping. If a teenager or a mom going through something like this reads it and feels any less alone, the whole project will be worth it. I hope they find me, and I hope they make their own art out of their broken hearts.