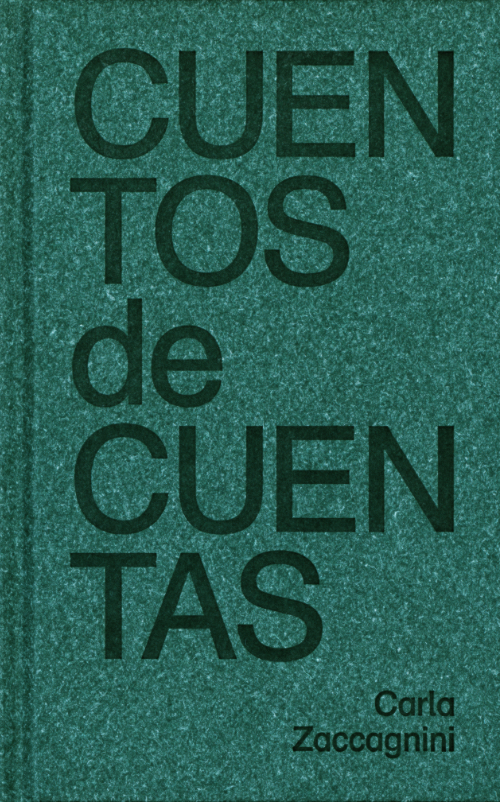

Written during the pandemic and released on the occasion of her concurrent solo exhibition at the Amant art campus in Brooklyn, Cuentos de cuentas (co-published in April 2022 by Amant Foundation and K.Verlag) artist and writer Carla Zaccagnini, who grew up in Brazil and Argentina during the turbulent decades of the 1970s and ‘80s, scrutinizes inflation, status, family, political and social uncertainty, under the guise of memory.

Cuentos de cuentas mixes English and Spanish to examine the complicated and unstable economy of memory in five vignettes. Peering through the often-distorted lens of photographic collage, ephemera, and appropriated stories, Zaccagnini asks of the reader: what is real and unreal? Here she defies genres in an artful mingling of history and memory, text and image, dollars and cents.

The book itself is a rich object, punctuated by vibrant pages of solid color, scattered images of the author’s drawings, archival clippings, ticket stubs, and other ephemera. It is at once a literary masterpiece and visual pocketbook. Its written investigations pair perfectly with Zaccagnini’s art installations, but they resonate far beyond the gallery, serving as a dialogue—a guide—to her visual work. Cuentos de cuentas invites readers into Zaccagnini’s kaleidoscopic realm of imagination, where she fuses domestic to historical, episodic to timeless, in effort to understand our individualized—and imperfect—perceptions of the past.

Leslie Lindsay: At the café where I read Cuentos de cuentas, I found myself eavesdropping. It was located in an affluent area, and conversations ranged from the economics of an upcoming “celebration of life” to the ethics of silencing notifications; they were a tangle of hope and hype: vein clinics, star smiles, and eyebrow threading. As I listened, I encountered this line: “Look, I brought you an idea.” My mind immediately morphed ‘brought’ into ‘bought.’ Are wants insatiable? Can ideas be bought?

Carla Zaccagnini: This is a beautiful way to start talking about this book, through words that are not in it, but were floating around it while you read. There is a passage in the Spanish version of the first chapter that couldn’t be translated. I mistyped the word “blanco” (white) for “blando” (soft) when describing a scene in which I fell down the white—or soft—marble stairs of my childhood home. I kept the typo, which is somehow like a faux pas, a misplaced step, a (Freudian) slip that can make one roll down the stairs. But it can also reveal how the hardness of stone is impermanent; challenged by the flexibility of a body in movement; corroded by memory. Any Lacanian psychoanalyst—like my mother—would say that desire is, by its very nature, insatiable. I am not sure ideas can be bought, but they can most certainly be sold. What do people really get when they think they are buying ideas? Probably something unable to satiate their desire of possessing those ideas: a timid reflection, a tortuous refraction, an illustration, an illusion.

LL: What makes a person want so much? What gives things the power to enchant? Is there a limit to the desire for more?

CZ: One thing is the structure of desire; another is the logic of capitalism. Desire for the other, and for the other’s desire, desire for difference, for the unachievable, is the motor that can make us move beyond what we know. Nothing good can be said about the logic of capitalism, the compulsive craving for excess and all the misery and destruction it creates.

LL: The same could be said about creativity. Some fear their creativity will be “all used up,” the well will run dry. In fact, the more one creates—or is around those who create—more ideas flow. This circles back to the consumerism of ideas, is there ever a “collapse of market”?

CZ: The well might be a good metaphor. A well is not an impermeable vessel, containing a limited amount of liquid that can be administrated to last as needed. Water does not belong to the well. A well is nothing but a passage. A well is the extraction of earth, an opening, an emptied space that gives access to aquifers, which extend beyond borders and are part of the continuous water cycle. The economy of ideas is similar. We are not born with a limited amount of ideas to have, and our ideas are not isolated in impermeable brains.

LL: In terms of art, might it be presumptuous to suggest artists get out of the studio and onto the streets? For example, viewing art in a gallery is one thing, but in Cuentos de cuentas, one can experience art as text, anywhere, as I did in a café. In that sense, you shifted the way people normally see things; maybe you shattered the optical subconsciousness by offering a dialogue. Perhaps you intended something else?

CZ: On different occasions and using different strategies, I have been attempting to establish with the readers of my work the same kind of relationship that literature has with its readers. Something parallel to the fact that you can bring a book with you, to the café or the park; that you can force the letters to shake with the subway or make the pages grow thicker with rain. The fact that places end up being imprinted in a book: the smell of sunscreen accompanied by a few grains of sand hidden between pages; the metallic smell of house keys in a book that has been in a purse for long; the receipt from a restaurant or a bus ticket marking a page with a passage that we cannot recognize; the alien underlined words that are like a present in a book from the library. The fact that you can read faster and without pause when you need the story to develop; or you can close the book and make the characters wait. You can go back some pages, re-read a paragraph, skip a passage, abandon the book altogether. The fact that you lend the printed words your voice, your accent, your rhythm.

LL: Punctuated throughout Cuentos de cuentas are color plates, like paint chips, which speak to the artistic quality of your work. Color theory combines context and harmony with the color wheel. Broken into elements, this might apply to the larger construct of your overall message: the context of consumerism, world citizens of all colors operating in harmony, and the gears of capitalism. Was that your intention with the blocks of color?

CZ: The color plates in the book are a printed approximation of how I remember the shades mentioned in the text, a reaffirmation or a correction in relation to the color each reader envisions when reading the words “army green,” “raw cement,” or “French flag”.

When Anna-Sophie Springer, editor at K. Verlag, read the first chapters of the book, she noticed the recurrent presence of color in the narrative. These stories, witnessed from the perspective of a child and recalled after decades, have a shallow depth of field: some details are in sharp focus, a lot of it is blurred. Some colors are focal points, as vivid as some smells. Around them are the “permissible circles of confusion,” as photographers call the areas of the image perceived by the human eye as being in focus. These colors are condensation points of whatever substance memories are made of. At least for me, memory matter becomes thicker as the abstract density of colors than as lines and scale.