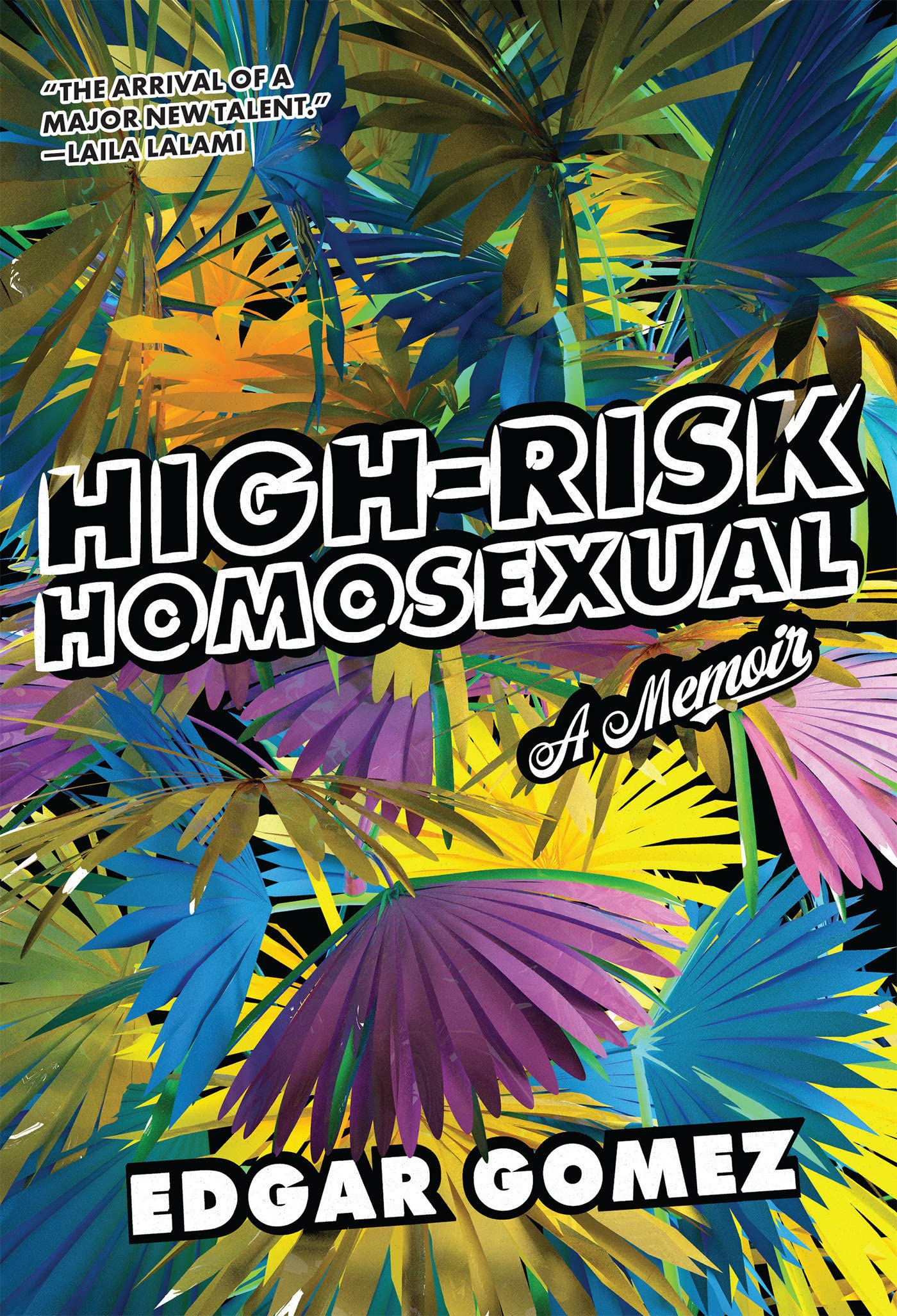

Edgar Gomez is a Florida-born writer with roots in Nicaragua and Puerto Rico. Their debut book, High-Risk Homosexual: A Memoir, has received universal praise—and let me add my voice to this choir of accolades. Rich in detail, intelligence, and emotion, High-Risk Homosexual is a literary joy and a vital addition to coming-of-age memoirs. Gomez does not shy away from the difficult truths of growing up Latinx and gay in a world that is too often cruel and unaccepting. But with grace and humor, they have served up a remarkable, inspiring, and poignant book that belongs in every library and on every high school and college reading list.

Gomez graduated from the University of California, Riverside’s MFA program, and their words have appeared in many publications including Poets & Writers, Narratively, Catapult, Lit Hub, The Rumpus, Electric Literature, Plus Magazine, and elsewhere online and in print. I spoke with them about the possibilities of memoir, the utility of labels, and High-Risk Homosexual.

DANIEL A. OLIVAS: High-Risk Homosexual is your first book. How did you decide to introduce yourself to the literary world with a memoir rather than a novel or short-story collection?

EDGAR GOMEZ: When I first started writing as a kid, I was all about fiction. I’d sit down and start inventing things and for some reason I didn’t understand, up through college, that pretty much all of my characters were straight, white, usually rich people. This wasn’t intentional. It just never occurred to me that they wouldn’t be. Those were the kinds of people that were written about in the books I grew up with and so those were the kinds of people I wrote about. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was writing in the tradition of queer and other marginalized folks throughout history who weren’t able to speak openly about their lives and so used other, more “palatable” characters to tell the stories they wanted to tell.

It wasn’t until I started taking classes in college with professors who asked me to write nonfiction that my stories—for obvious reasons—began to have people who looked and spoke like me, came from the same places. In retrospect, even when I was writing for fun and wasn’t thinking about being a Writer with a capital W, I didn’t believe someone like me could be the main character. Even then I’d internalized the demands of a publishing industry that is often racist/homophobic/et cetera and puts certain voices on a pedestal and accuses others of not being “marketable,” which we know isn’t true. Those demands are still there in nonfiction, but there’s something nice about not being able to change the facts of my life. Even if I wanted to be more marketable, there’s a limit to what I can do to make that happen. I love being limited in that way, because I sometimes worry that if I wrote fiction I’d go back to being that student who was afraid to center themselves.

DAO: Writing is hard, lonely work, though for many, including me, it can be incredibly fun and exhilarating especially when readers start to react to your efforts. How would you describe your process of writing your memoir including the difficulties as well as joys in writing it?

EG: At this point in my life, I’ve probably had over 60 jobs, from selling bootlegs CDs at the flea market as a kid, to cocktail serving at a gay bar in Hell’s Kitchen. And to be honest, writing might be the easiest job I’ve ever had. That doesn’t mean it’s not hard, but I’m constantly grateful that I get to do work where my creativity is valued and I’m not breaking my back, though writing does require you to hunch over for hours.

My process is straightforward. The majority of the time, I already have one big memory that I know I want to write about. I may not know what the story is, but I know there is a story hidden in there somewhere. I open a word doc or the notes app on my phone, vomit out as many details I can remember about that memory, and after about a month of doing that, I have what amounts to a bunch of puzzle pieces. I use those to figure out what picture to make. That’s the hardest part, because there’s so many different directions that you can go, and also because I want to make sure that the picture is interesting and useful to other people, not just me. There’s no guaranteeing that it’ll happen, but when someone does tell me my story helped them, it feels like magic every single time.

DAO: Labels play a key role in your memoir: Latino/a or Latinx. Gay or straight. High-risk or low-risk. In your view, what are the dangers of labels? Can labels play a positive role in life?

EG: I don’t believe labels are always the worst thing. I want to know what kind of milk I’m buying. I want to know if I’m going to a gay bar and if it’ll be Latin night and they’ll be playing salsa or reggaeton. It’s when we apply strict, fixed labels like that to human beings, who at our best are always growing and adapting, that things get trickier. I’m a Pisces (does this count as another label?)—I’m always changing my mind.

The most off-putting thing to me about labels isn’t the labels themselves, but who is doing the labeling, because they’re often used to continue harmful agendas. “High-risk homosexual,” for one, is not something I would have called myself when I applied to be on Truvada, a once-a-day pill that reduces your risk of contracting HIV, but the medical system in the U.S. did. I see a direct link from that label to the misconception that only queer people contract HIV, which leads to violence against the LGBTQ+ community as well as to members of the heterosexual community who think HIV is just a gay disease. Like everything else, labels can be good in moderation. And let people decide who we are for ourselves.

DAO: In your acknowledgements, you thank many loved ones and mentors. But you also say that you “want to hold space for the queer people who lost their lives at Pulse. I will think of you and thank you my entire life.” You then offer “rest in peace” before listing them by name, the vast majority of whom were Latinx. It is a very moving manner to conclude your debut book. Could you talk about why you’re grateful, and what such a loss tells us about our society?

EG: The shooting at Pulse was more than a headline for me. The people who died were people I danced with on Saturday nights, who bought me drinks, who stood next to me at drag shows and cracked jokes with me in line for the bathroom and offered me community when I was at my most lost. They were people who, at a time when the world tried to convince me that being who I was would only lead to pain and suffering, showed me joy.

Losing them is another reminder that this world has a lot of healing to do. The shooter was someone who had a lot of internalized hate, racism, and homophobia ingrained in him. I think of the lives he took whenever I feel like my work on this earth is done, and whenever people outside my community claim there is no danger to our human rights. Remembering them makes me acutely aware of how lucky I am to be alive and fighting.