At the end of Emily Hall’s debut novel The Longcut, the book’s unnamed narrator runs through the streets of New York toward the studio of an artist friend, brimming with a story to tell. “What was important,” she thinks to herself, “was to not find the right words.”

This revelation, the culmination of over a hundred pages of mental meanderings from the point of view of an artist struggling to pin down the meaning of her work, reminded me of a conversation published in The Margins in 2017, between the poet Jenny Zhang and the memoirist T Kira Madden, in which Zhang described a particularly tantalizing desire to “waste” words:

I want to be wasteful with language…. I do love spare prose, but there can be a misogynistic attitude about it. An attitude that says women should be prim and neat and not spill over and please take up as little space as possible and walk around with your shirt tucked in nicely and your slip can’t be showing; I don’t care about that.

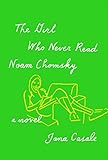

Despite the degree to which this interview resonated with me at the time of its publication, I’ve been, like many writers, deferring the decision to shape language in a way that spills over and takes up space. I’ve long thought of unruly prose as an indulgence, a potential to be explored only under ideal circumstances. As if angling for permission to write this way, I have searched for examples of it in novels, particularly those about intelligent, neurotic women (for instance, Christine Smallwood’s The Life of the Mind or Jana Casale’s The Girl Who Never Read Noam Chomsky). In The Longcut, I found, possibly for the first time, a genuine expression of what Zhang might call “wasteful language.”

Hall’s prose has that white-hot, unedited, circular logic of a first draft, the kind that pursues every agitation and impulse down its respective rabbit hole. The narrator swerves, for instance, from discussing the cost of her materials to wondering “what was Cambridge blue, why was no aria by Handel as beautiful as ‘Forte e lieto,’ what was the difference between perhaps and maybe, when did a handshake begin and end.”

Conspicuously casting off traditional narrative concerns like rising action and character development, The Longcut blends elements of flânerie and stream of consciousness, allowing the narrator’s mind to grasp far and wide beyond the single day in which her story is circumscribed. When we first meet her, she is on her way to a potentially career-advancing meeting with a gallerist, a meeting set up by her artist friend whose work, we learn, is better-known and more conceptually unified than hers. However, all we know about our narrator and her art is that she works with a “small suitable camera.” She has made photographs of a granite egg, as well as a film about a construction crane outside her office window. She eventually gets the idea to make “carryaround sculptures”—small sculptures that would reside in people’s pockets—but cannot decide how these sculptures should look. “They—the carryaround sculptures—were an idea but not a form,” she admits.

For such an artist’s story, Hall chooses the form of a monologue that twists and turns over the course of a hurried walk down the “long side” of Central Park. Curiously, the author manages to write a perambulatory novel that, like Zeno’s arrow, stays fixed in one place. She also manages to lodge readers firmly in a woman’s subjectivity while withholding the vast majority of her emotions, memories, and motivations. It’s a fascinating project, one that prompts readers to ask in the end: what can wasteful, imprecise language—paired with a minimalist approach to plot and character—reveal about the world?

In The Longcut, this pairing boldly reveals the unmediated, unadorned, and unpolished shape of thought. The catharsis of thought—interrelated ideas and their movement through time—provides an unrelenting central tension. As is the case in novels like Brenda Lozano’s Loop or Ariana Harwicz’s Die My Love, the tension lies not in what the narrator will do next but in what she will think. Of this our narrator is conscious. She seems to know that the reader is analyzing her thought patterns. “Was my cognitive space a loop, a constant returning,” she wonders, “or was my cognitive space a knot, or not a knot but a tangle, a tangle anchored by a spike which if pulled would allow the tangle to instantly resolve itself.”

In The Longcut, this pairing boldly reveals the unmediated, unadorned, and unpolished shape of thought. The catharsis of thought—interrelated ideas and their movement through time—provides an unrelenting central tension. As is the case in novels like Brenda Lozano’s Loop or Ariana Harwicz’s Die My Love, the tension lies not in what the narrator will do next but in what she will think. Of this our narrator is conscious. She seems to know that the reader is analyzing her thought patterns. “Was my cognitive space a loop, a constant returning,” she wonders, “or was my cognitive space a knot, or not a knot but a tangle, a tangle anchored by a spike which if pulled would allow the tangle to instantly resolve itself.”

Tellingly, while filming a crane outside her office window, the narrator refuses to fast-forward the recorded footage; doing so, she argues, would prevent her from having the same experience as a potential viewer—that of the monotony of the office window punctuated by unpredictable appearances of an intriguing object. In another instance, the narrator admits she likes taking the long way from place to place—the “longcut”—more than she likes shortcuts, which, according to her logic, foreclose the process that separates art from mere gesture. In that both are winding and purposely time-consuming, the shape of the narrator’s thoughts is inextricably linked to the path she chooses to walk.

The world within this slim novel is clearly observed by a writer who shares the practical and conceptual concerns artists have for their art, as seen in the scrupulous attention Hall’s narrator pays to the durational aspect of her construction crane film. The book also scrutinizes social relations and behind-the-scenes labor in the art world, showing us how objects circulate and how discourse is molded. However, Hall’s criticality demystifies, as well as dampens, the subject matter of her book. Manhattan is maligned for being as wasteful in its presentation of art as the author is with language.

“I could be looking at page after page of gallery advertisements in an art magazine,” the narrator states, “or looking at artworks in one gallery space or gallery window after another,” and in these spaces, she laments, all the social transactions and work hours that have gone into making a work of art are flattened into empty signifiers that gesture noncommittally toward meaning—“art being the theme and different artists’ work being the variations.”

As a reader hungry for nuanced discussions of art and process, close visual analysis, and ekphrastic experimentation, this sentiment left me feeling both desensitized and impatient. I had hoped for either a more comprehensive or a more challenging take on the state of contemporary art. Instead, feeling glutted and numb, overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of art around her, the narrator likens the works to “so much merchandise on display… one thing meaning precisely as little as another.”

This particular topography, in which galleries sit on top of one another, competing for viewers’ scattered attention—this surplus of art and its social and economic scaffolding—is an attribute of many major cities, but not all. Those living in areas without such easy access to art spaces and galleries would likely be less blasé in dismissing large swaths of contemporary work as mere merchandise in a featureless grid. However, the satirical—and therefore purposely narrow—discussion of art in The Longcut reduces the endeavor to a binary: starting point versus end point, privacy versus exposure, question versus answer, the artist versus the commercial gallery. If anything, after reading this book I felt grateful that the art world consists of more players than just the artist and the gallerist, that it is buoyed by, as Hall’s narrator observes, vast and unruly networks of collaborators, for whom copiousness is not a burden to carry but a salve for the rest of life’s discontents.

Perhaps we can think of the state of contemporary art described in this novel the same way we approach Hall’s subversively “wasteful” approach to language. The shape of thought, in this case, morphs in accordance with the shape of the city. For the flâneuse, and particularly the artist, thought is a provisional, shifting street. The more the city rambles, the more it expands both upward and inward, so too does the mind.