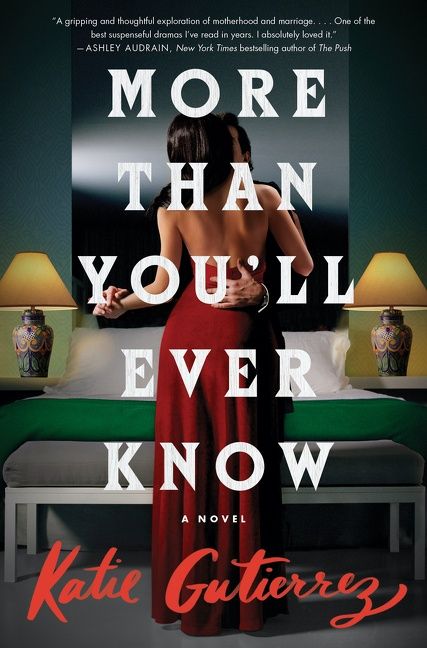

Katie Gutierrez’s debut novel, More Than You’ll Ever Know, out today from William Morrow follows two central characters: one, a Mexican-American mother named Lore whose double-life in the 1980s results in one of her husbands convicted of murdering the other; the other, a white aspiring true crime writer, Cassie, who is hellbent on telling Lore’s story. Both women have secrets buried deep that, over the course of the novel, refuse to remain underground.

Over a mid-morning Zoom, I spoke with Gutierrez—who is also a prolific essayist, with work published in Time, Harper’s, Catapult, and elsewhere—about true crime, the many versions of ourselves, women’s ambition, the writing process, and our innate pull toward darkness.

Shannon Perri: More Than You’ll Ever Know plays around with the truth, and really questions the nature of truth itself. But throughout the novel one truth affirms itself again and again: we all contain multitudes. We all have the capacity for multiplicity. What drew you to this idea?

Katie Gutierrez: I’ve always been fascinated with the ways that we compartmentalize ourselves, the ways that we change depending on who we’re with. We can be one person with our husband, another with our best friends, with our mothers, with our children, with strangers. We’re all constantly presenting different parts of ourselves to the world depending on how comfortable we are or what we want.

When I was in my MFA program [at Texas State University], sometime around 2011, I read this story about a man with a double life who’d been with his wife for thirty years. When she died, he married another woman two weeks later. At that point, people were like, Who is this woman? It turned out that he had a whole separate family with her. They lived 20 miles apart. He had two kids with each woman, and they all went to the same school at different times. He bought both wives the same white Lexus. That he could compartmentalize himself so completely was this extreme version of what I had always been interested in, but I wanted to explore that from the perspective of a woman living a double life. I feel like women are especially forced to compartmentalize themselves. I wanted to take that concept of, like you said, the multitudes, and take it to an extreme, the ways that we all do every day.

SP: Much of the tension in this book exists between motherhood and familial responsibilities versus ambition, and the ways women get punished for being ambitious.

KG: With Lore and her first husband Fabian, I was interested in exploring two people who love each other and are good together in many ways, but are put in this pressure cooker situation. Especially in Mexican culture, there’s that element of machismo, and expectation that men will be the providers. When that can’t happen and the roles are switched, that can put pressure on even the best relationships. I wanted to explore the impact that might have on an otherwise fairly good marriage. If a woman’s ambition and success were to outdo her husband’s, what could happen?

SP: The novel is masterfully plotted. How much of the story did you know before you wrote the first draft and how much was discovered through revision? What was the initial seed?

KG: I mentioned that double-life story that I’d read, and that was probably the initial seed. At the time I was working on my thesis for my MFA, which was a collection of short stories set in South Texas. I had this idea of a woman living a double life and of there being a frame story with the reporter, but it felt bigger than a short story, so I shelved it. After I got my MFA, I had a full-time job as an editor for many years. When I stepped away to focus on writing, I was working on an entirely different book and that took a couple of years, and when that book didn’t sell, this double-life story idea was still in the back of my mind.

I started playing with the characters and trying to figure out who they are. Who is this woman living this double life? How does she pull it off? Especially in this day and age of being online, where everything and everyone are so connected? It felt obvious that it should happen in the past. Setting it in the past also created the opportunity to explore truth in a different way—what if the events known to have happened didn’t actually happen that way, or what if there was a deeper story behind them? That opened a different door for exploration and tension between the characters. The next question was, where does it take place? I grew up with my parents telling stories about this time in the 80s, with the peso devaluation. I liked the idea of setting it [in Laredo] and playing with the idea of doubleness in this city that I grew up in. It’s a border town. The city itself exemplifies duality.

Every decision led to another decision. Before starting to write, I like to have 50 to 60 percent of the book sort of outlined. I was using Scrivener for this, and I used the cork board feature to take any scenes that I could already envision in like a one-line synopsis and order them in the way that I thought they would go. The structure of the book changed fundamentally across probably twenty different drafts. The first draft was a mess—it was 600 pages. The 150 pages were all Lore’s perspective and then it switched to Cassie for the next hundred, and my agent was like, Yeah, this is not working. There was a lot to do in terms of braiding their stories and trying to make sure that both women were equally compelling. I realized that I didn’t know Cassie as well as I did Lore. I learned a lot about Cassie in the writing process. Lore as well, but Lore came to me whole for some reason.

SP: The novel made me fall in love with Mexico City, which plays a central part in the story. I’ve never been, but now I desperately want to go. Did anything surprise you in your research about Mexico City?

KG: I actually have not been to Mexico City either. My family is all Mexican and I’ve been to Mexico a few times over the years, but less so after the violence got worse. In researching Mexico during this time period, I was able to get closer to my culture. I really enjoyed that aspect of it. I had planned to go to Mexico City several times, and then the pandemic hit. That’s a big regret I have with the book, because no matter how much research you do into a place, being there physically will always change it. Maybe not fundamentally, but being able to add those sensory details would’ve made a difference, so I’m sad that I didn’t get to.

Mexico City was one of those pieces of the story that I didn’t know would be so central in the beginning. Probably my research about the 1985 Mexico City earthquake was—it seems weird to say my favorite research because it was so tragic, but it was a piece of history that I wasn’t aware of. I was just a kid when it happened, and it was so unexpectedly moving to read firsthand stories and to see photos and find articles and explore archives from that time period. There is a moment in the book where Andres, Lore’s second husband, is telling her about a little boy who was stuck in the rubble for a week or so before dying; that boy was a real boy that I encountered in my research.

SP: In some ways this book is a traditional crime story and in other ways interrogates the true crime genre itself. Given that, were there challenges in deciding what to reveal and when? How did you approach plotting a crime narrative while critiquing the way true crime narratives are told in the first place?

KG: Yes, especially with Cassie. With Lore, I always saw her as this unapologetic character putting it all out there but in sort of a self-serving way. Her revelations feel true and intimate, yet she’s very careful about the way she constructs her own story. Her character is all about the stories we tell ourselves, the narratives we create from events in our own lives, how those narratives change and become what we need them to be at different times. With Lore, I wanted everything about the affair and the marriage to be upfront; I wanted the tension to be between what the reader knows that the husbands don’t.

With Cassie, there were different points with her mother, father, and brother, that were withheld. It was a challenge to figure out when to reveal those things so that it felt compelling, but not manipulative. With Cassie’s perspective, I didn’t want to be withholding as a way to falsely build suspense. I wanted to earn it, so it was a challenge figuring out where the sweet spots of those revelations would be, and those also changed in different edits. I also was interested in her own personal blind spots. Cassie withholds information from the reader, and in a lot of ways, from herself.

The last third of the book became a much more traditional whodunnit with those revelations. My U.K. editor works primarily with crime fiction, and so he was really focused on the suspenseful elements and the plot points, and he helped with a lot of the pacing in terms of when those revelations were made and how they were made. It was a great complement to my U.S. editor, who was very character focused.

SP: You recently wrote an essay for Catapult about the ethical challenges of true crime and the possibilities of crime fiction. Why do you think so many of us find crime stories pleasurable, and for some, even comforting? I have friends who watch true crime shows or Law & Order: SVU to help them fall asleep.

KG: I’ve totally done that. There’s something so morbid when you consider these shows are about people whose loved ones are probably still mourning them; meanwhile here’s a person putting the story of their murder on in the background to help them fall asleep. That is such a strange juxtaposition. And I think part of the comfort of episodic shows like SVU, in which each episode is self-contained, is that most of them have satisfying conclusions. Nine times out of ten, they’re going to catch the person who did it, and there will be some level of justice or catharsis. In turbulent times, which we’ve been living in, there is a level of comfort in knowing that soon, you’ll know what happens.

There are so many different elements of why true crime is compelling. The fact that it’s proliferated into all these different categories—books, podcasts, prestige documentaries, network TV—no matter your mood or your personality, you will find a genre of true crime that appeals to whatever you’re searching for. Rachel Monroe does a great job of identifying these archetypes that people are drawn to, and maybe some of them overlap and maybe you identify more with one archetype, the victim in one story and more with the detective in another, but there’s a level of personal investment we place into our true crime stories. We latch onto one of these characters, we have something emotionally at stake in knowing what happens to them.

Then there’s part of us that just has that dark curiosity. It’s like not being able to look away from a car wreck. We are drawn to things that we don’t understand and can’t comprehend. Also, like I said in the Catapult piece, men are murdered much more often than women, but when women are murdered, there is often sexual violence involved, and so many women have experienced sexual violence in their lives that I think it can be validating to see their world reflected back, particularly when justice for sexual violence is so rare.

SP: It’s common for parents, especially new moms, to be flooded with visions of the worst thing that could happen to their baby, and sometimes that can weirdly be—I don’t know if comforting is the word?—but, for me, l would think, “if I imagine it, it can’t happen.” It reminds me of what you said about our pull toward the dark.

KG: That’s so true. I did that a lot, particularly with my first baby. I think I had undiagnosed postpartum anxiety. Just those repetitive, compulsive imaginings of the most horrible things that could possibly happen. It was so endless and on a loop, and like you said, I felt like I had to think of everything from start to finish, and if I could, then I’d somehow prevent it from happening. I think that can be part of it as well with true crime stories, especially if we’re identifying with the victims. There’s an element of, Okay, let’s take note of what they did or didn’t do so that we can protect ourselves better.