To read the poetry of Ada Limón is to enter mysteries around life and nature and the world for which she has no answers. She distrusts her own role as an observer and tries to de-emphasize herself, understanding that she cannot truly understand the changing people and creatures around her. As she writes in “Intimacy”:

a clean honesty

about our otherness that feels

not like the moral, but the story.

Her new book, The Hurting Kind, is her sixth collection of poetry and the titular poem about the death of her grandfather captures a lot of this. It is a poem with multiple registers, that seeks to talk about his life and how he would have wanted to be remembered, talk about her grandmother and her family, about how individuals grieve and how a family grieves. It tries to celebrate him while also understanding that he didn’t want to be celebrated. He saw himself as ordinary and Limón wants to record the moment as something ordinary. Grieving is a common human experience, but that doesn’t mean that it is not sacred and important and powerful. Her grandfather was both ordinary and important, and Limón feels similarly about so many things, seeking to celebrate things even as she acknowledges their ordinariness.

Limón is also the host of the podcast The Slowdown, which comes out five days a week, and we spoke about what a poet does with missing, the human and animal experience, and how her mother paints all her book covers.

Alex Dueben: Thanks again for doing this. And it’s nice to see you. I listen to you daily on The Slowdown, so it’s odd to see you because I know your voice so well.

Ada Limón: That’s wonderful! I’m alone a lot and writing these things by myself and then I’m recording in my bedroom and so when people tell me they listen I’m like, Oh good! There is someone out there!

AD: I’ve never been to one of your readings, but your poems have a musicality. You’ve always seemed very interested in the sound of a poem.

AL: I am. I want to say the sound is the biggest driver for me because I’m interested in music, but I’m also interested in how the poem really is like music on the page. It really is a whole-body experience. It’s meant to be read out loud. It’s meant to be in the mouth and the ears. Not just the eyes. It’s not really meant to be read in a quiet silence. It’s meant to be heard. Even if you just read it out loud to yourself. I always think of poetry as very close to music.

AD: Like a piece of music, a poem doesn’t resolve the way a narrative does, but it does conclude.

AL: That is a great way to put it. I think that one of the most important things about poetry is that it doesn’t provide answers, but it does transform something. Even in the smallest way. The way music does. It can wash over you and you can feel different on the other side of it. It is remarkable to me that I can be a changed person on the other side of one single poem. Not just writing it but reading someone else’s poem. I have experienced something and now I am different. Just from this one page of words. It’s really so remarkable to me.

AD: On The Slowdown this week you read Shelley Wong’s “Walking Across Fire Island” and in introducing the poem you spoke about walking and you used this phrase that’s been in my head: “You put your body into the world and something happens.” It sounds like you feel that same way about a poem

AL: I do. I struggle a lot with the idea of inertia. The idea of what it is to be quiet and observe and just watch. When to go into the world and can you be an observer while you’re moving into it—and how those two things collide. I think about that all the time. That’s the way birds experience the world. They’re experiencing it from flight. They’re experiencing it running on the ground. I find that the physicality of both poetry and the experience of the world really interesting. We live so often in the mind. [Laughs.] I mean, I’m that way. I can sit for a long time and just be alone with my thoughts. I’m grateful that I have a little dog next to me that gets me out into the world. Remembering the body, remembering the animalness of me as opposed to that chaos and mayhem and beauty that’s in the brain. I love spending time there. Even gardening. Just doing a simple task like preparing the beds and planting the lettuces feels like almost a spiritual practice.

AD: It’s a practice, which is true of writing and religion and politics and so many things.

AL: We often think that poetry is an act of the mind and I find myself fighting against that a lot. I think it’s bigger than that. It’s connected to all the parts of the body. It’s really connected to the breath. It’s made of breath. That space, that cesura, the line breaks, the stanzas—that’s all breath. And that’s one of the most essential movements of the body. I think sometimes we forget that and think that, no, it’s an intellectual act. It’s that, too, but I like thinking of all the elements that go into it.

AD: As far as organizing the book into these four sections. To everything there is a season, of course. But in writing about nature and family, which I think are the central themes of the book, how does it make sense to organize this book into spring, summer, fall, and winter sections?

AL: Nature and family, for sure, are the themes. Putting together a book is actually really fun for me. I think that part of it is that it always surprises me. I never try to rush it. I think my publisher was asking for this book for a while and I was like, I don’t know. I don’t have any poems. Of course, I did, but I’m not going to say that. [Laughs.] I like to really feel ready. I was really surprised by the seasons because I’ve never organized a book that way. It’s not something that I was expecting, but I realized that the book has so much to do about time, simultaneity, the non-existence of time. And also cycles. What was wonderful about it when I figured that out, was that it de-centered me in some way. That instead of the narrative being “my” narrative—Ada Limón, the speaker of these poems—it became a larger narrative. A narrative of not just my community, and not just animals, but of the world itself. Even though it’s very much me. I’m in the book. But I wanted a sense of ongoing-ness that didn’t necessarily involve my physical presence in the world. When the seasons came, I thought, that’s it. That’s how it needs to be organized.

AD: As we were saying earlier, that gives this sense of movement and time passing, but not necessarily a sense of ending.

AL: The way that “The Hurting Kind,” the titular poem, ends—“Love ends. But what if it doesn’t?”—I think that that’s also part of it. That ongoing-ness. There was a part of me that thought, it would be lovely to finish reading the book of poems—I know most people don’t read a whole book of poems in one sitting, but I do.

AD: So do I.

AL: [Laughs.] We have that pleasure. We call it “work.” [Laughs.]

But I love the idea of finishing the book and then starting it again. The idea is that it begins again. Because what comes after winter? Spring. That sense of cycles and returning and ongoing-ness and de-centering. It wasn’t something I was planning when I started gathering the poems and seeing what shape it would take.

AD: Family is central to the book. The titular poem is the center of the book, but in poems like “Joint Custody” and “Sports” and “Runaway Child,” you write about what family means and how it’s understood and how that changes over time.

AL: I think that’s very true. I really was interrogating the idea of connectedness and how we see ourselves in relationship to the world. I’m always fascinated by that. What we claim as our identity. I was so curious as to what would it look like to ask myself some serious questions about that. Also, lean towards gratitude and appreciation and affection in that interrogation, so that it became a way of really seeing deeply what other people have offered and given in order for me to have this life. I don’t know about you, but I think the last three years with the pandemic and the climate crisis and now the war—not to mention the racial reckoning going through all of that—made me really want to lean into connectedness and the people who have sacrificed and given me permission to do what I do. To live the life that I am living.

I also think that because I was separated from everyone and couldn’t travel and couldn’t see anyone. Now, not all these poems were written during the pandemic. There’s probably five years of poems in this book. But I would wake up and miss my dad. What do I do with that missing? Well, I zoomed with him and we had cocktails and all those fun things, but what does a poet do with missing? We write poems. These are real gifts that I could send and be, Hey, I wrote this poem for you. They weren’t exercises. They were offerings to real people in my life.

AD: There are a number of poems in the book which on first reading I thought, these are pandemic poems, like “Banished Wonders” and “Blowing on the Wheel” and “Lover.” But on rereading, they’re not necessarily pandemic poems. “Lover” is a winter poem and a pandemic poem—and it’s neither of those things.

AL: Like I said, there were many poems that were not written in the pandemic, but some were. I wrote “Banished Wonders” over the first summer where it felt like everyone was just, Okay, this is it. Also, I always go to South America during the summer and that idea of the world’s just closed and what does that mean? But also trying to figure out what are the wonders here?

I like that sense that it can be translatable and into different eras and times because this is a unique and tragic time, for sure. Especially if you consider the climate crisis that we’re in. And at the same time, I think about how so many people have lived through so much and to acknowledge that this is a unique time, but every time is a unique time. I want to work against the preciousness of the individual “I” experience. That this moment is all there is. Yes, this breath is all there is. But I want to push against that I’m the only one who’s ever gone through this kind of thing. So many people have gone through so much globally and through history that it feels a little false sometimes to privilege our own suffering in a way that makes it seem more important than other people’s experiences.

AD: Having so many poems about nature and the way you structured it with the seasons gives that sense of recurrence. Similarly to reading a love poem, poems about isolation and loneliness and death are unique and they’re also very much not unique.

AL: They’re the human and animal experience.

It’s easy for me to get carried away in my own little world and it’s good for me to place it into the larger context. Larger of all of us. That kind of de-centering is important. That doesn’t mean that I don’t feel, that I don’t grieve, and I’m not cheerful and I’m not going through my own thing, but I still remember the first time I realized that everybody lost someone. [Laughs.] I mean I was in my 30s and I was like, Oh, everyone’s going to lose their mom. Everyone! It’s interesting to me that we don’t acknowledge that as much. We feel whatever we’re going through is so deeply personal. We don’t talk about it. Of course, if we do talk about, we realize everyone’s going through this.

AD: I love how you talk about and use nature throughout the book. You have a line in “Privacy”: “they do not / care to be seen as symbols.” You’re writing about nature not as metaphor but being a witness to nature and being witnessed by the natural world.

AL: That was really important to me and that’s part of that idea of what it is to really be connected. What it is to not always be the watcher. To not always be, I’m going to look and because I am looking I am the narrator. [Laughs.] That’s part of my work. There’s a part of me that’s like, what does the bird think of me? I always laugh that the birds are thinking, Lady! The feeder’s empty! I think the birds call me lady. I’m an animal moving amongst their space. It’s not “my” backyard. No, my house is in their world. [Laughs.]

AD: Someone built a house in their field.

AL: Yeah! [Laughs.] We have a weird ownership of things that doesn’t make sense.

AD: You make clear that to deal with nature is to encounter and embrace this mystery and magic and an unknowability.

AL: I’ve been thinking a lot about how I miss knowing things. [Laughs.] I do! I feel like when I was in my 20s, I knew so much. I know it’s cliche, but it’s so true. I don’t know. If the last three years have taught us anything, it’s that we know nothing for certain. We don’t know what’s next. I think this book is in some ways a way of coming to terms with that. Finding beauty in that instead of being terrified of that, which is partly the emotion that happens when you realize you know nothing. Just being at peace with that and realizing, Oh, that is part of the human condition. That surrendering. That doesn’t mean you don’t try to figure it out. That doesn’t mean you don’t question and live in wonder and awe. But you’re not always trying to make sense of everything. I found a lot of peace in that. I could roll with that. That was something I could move in the world with.

AD: I feel like you’ve written a few poems over the years about your husband’s ex’s cat. That strange changing unknowing mystery isn’t just about animals, but people too, and embracing the strangeness.

AL: And how much we’ll never fully know about one another. I can never not be curious. I’m always going to be curious and want to know more. But I kind of love that I’ll never figure it out. And the changeability of people! I think we sometimes hold people to this fixed-ness. They’re supposed to be this or supposed to be that or that happened and therefore they’re bad. We change all the time. To make space for that is another way of recognizing our animalness. Recognizing our mortality.

I could write a million books and no one’s ever really going to know who I feel myself to be. That inner core. That self underneath the self. I could read a million Audre Lorde poems and a million Lucille Clifton poems and feel like I know them, but there’s still that mysterious human element. Whether you call it a soul or whatever, it is mysterious and unknowable and I love that. It’s another one of those sweet mysteries. I mean wouldn’t it be a bummer if we could figure it out? [Laughs.] If we could go, I know exactly who you are. You will only be that person.

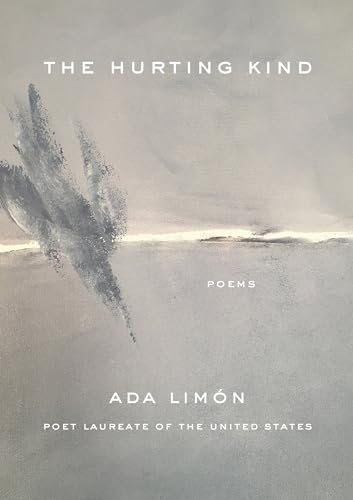

AD: I did want to mention the cover because your mother paints the cover art for all your books, and it’s such a beautiful way to communicate. Does she read the book and then paint something? Or paints many things and then you pick one? How does it work?

AL: Thank you for asking that. I think she’s an incredible artist. And of course, the first artist in my life. I feel like our process is really unique in the sense that she reads every single poem and she’s very articulate, but she always says that language is not her medium. She’s visual. I’ll ask, did you like the book? And she’ll say, I love it. But she’s the person who’s going to respond with, Here are 10 paintings I did. That’s our communication about my work. When I saw this one in her studio, I said, that’s it. I like the idea that it’s a gesture of a bird. It’s not really a bird, but the idea of a bird. Also, the bright seam on the horizon. I love that. But it’s a real gift because we don’t collaborate in any other way. Well, we talk every day. We collaborate on our lives.

We always had a relationship through language, but I think she really responds to me in her most big-hearted holistic way with the paintings. And so, to really have those on my covers feels like it completes it. And now it’s done. She gave it its completeness, its wholeness. It’s so beautiful.

AD: The titular poem is a winter poem about grief, and gray fits with both of those things. And that seam of light is the horizon. Or Leonard Cohen’s crack in everything.

AL: That’s how the light gets in!

AD: I wanted to talk about the titular poem, which as someone who has had relatives and friends die, captured some of that experience of grief and grieving. The ways you structured it, using multiple stanzas and registers, felt very true to that experience.

AL: Thank you. I think of all the poems in the book that took me the longest to write. It took me the longest to finish. I started it in May 2018 and probably finished it in 2021. I think the reason it was so hard to finish was because of that line in the poem, when my mom says you can’t sum it up. I have a moment where I don’t know what she means. She means a life. I’m driving and we’re getting things done and I just had a really hard time getting out of the poem. I’ll just keep writing this poem until I die. [Laughs.] I feel like there could very easily be a poem like “The Hurting Kind 2” in the next book. [Laughs.] It just goes on and on and on. I think the hard part is that there’s a part of us—and I’m very suspicious when I say “us” and “we”—there’s a part of me that feels we want people to see like the heroic parts of our dead. I didn’t want to do that. That felt untrue to my grandfather’s experience. He would have said, I’m no one. When I asked him what kind of horse he had, he said, it was just a horse. I feel like that’s him. That to me was really important. It’s hard to really write an elegy for someone who’s like, I’m just like everybody else. I had to honor that. There were probably 10 poems about him that were very heroic poems and I had to honor him because he would not have liked them. I had to make the poem not only about his passing, but also about my grandmother. He would have been good with that. Also that sense of, this is just the way it goes. That maybe this just continues. It’s living and then the remembering of living.

It was a really hard poem to write only in the sense that I really wanted to get that honoring right. It can feel a little prose-like and I wanted to make sure the music was there and that the tempo changed in different places. There are longer lines and then shorter more staccato lines. I wanted to have that because I think grief moves like that too. Sometimes it’s chatty. You’re getting things done and here are the funeral clothes and then sometimes it’s heavier and somehow rhythmic and formal. I think that that was part of getting the musicality of that poem right. Not making it all prose or one kind of line was important to me. Both formally and emotionally it was a tough poem to get right. And when I finished it, it felt like oh, maybe I have a book coming.

AD: Also, it captures how we grieve differently and in different stages. Like your mother having this reflective moment while you’re busy getting things done and to do that, you can’t be in your feelings. That feeling gets echoed in the different stanzas and registers and I think that is part of the experience of grieving.

AL: I think that’s absolutely true. I couldn’t not record all this stuff in my head. I mean I’m the person who drove and did the errands, and the other part of me—or the other part of my job—is that I remember these things. That’s my role.

AD: I wanted to mention the last few poems that close the book. “Salvage” hit me really hard.

AL: Me too. [Laughs.]

AD: [Laughs.] All those poems are beautiful and they follow “The Hurting Kind” and there is a flow and movement to them.

AL: Thank you. I really worked hard at putting the book together. That when you finished it, it would feel like reading one whole poem, even though each individual poem has its own life. Putting it together was very interesting because usually a titular poem is in the beginning or towards the beginning and it wasn’t supposed to be there. It was supposed to be where it was. I had to listen to where it wanted to be.

AD: You’re very good at concluding your books. There’s that old Stanley Kunitz line about “the dream of an art so transparent you can look through it and see the world.” In all your books, you have this way with the last poems of almost easing the reader off the page.

AL: Thank you. I believe so much in the power of poetry and language and what it does to us as humans. And what it can do. I deeply believe in the power of poetry. I take it seriously. There’s this other part of me that really believes in the power of connection. Getting out into the world. Watching things. Breathing. Being alive. I’m just as interested in being a good artist as I am in being a good and whole human being, and I want to offer that to the reader. You’ve lived in this world—now go live in your world. Go live in the natural world. Or in community with whomever you’re with, whether it’s animals or plants or humans. I think someone asked me about [the final poem] “The End of Poetry” and they said, it seems like the last poem you’ll ever write. I said, “No! It’s just the end of poetry for that day.” [Laughs.] Or for that minute. Or for that month. But it’s about setting it down.

AD: Don’t pick up another book immediately.

AL: Exactly. Go back in the world.