1.

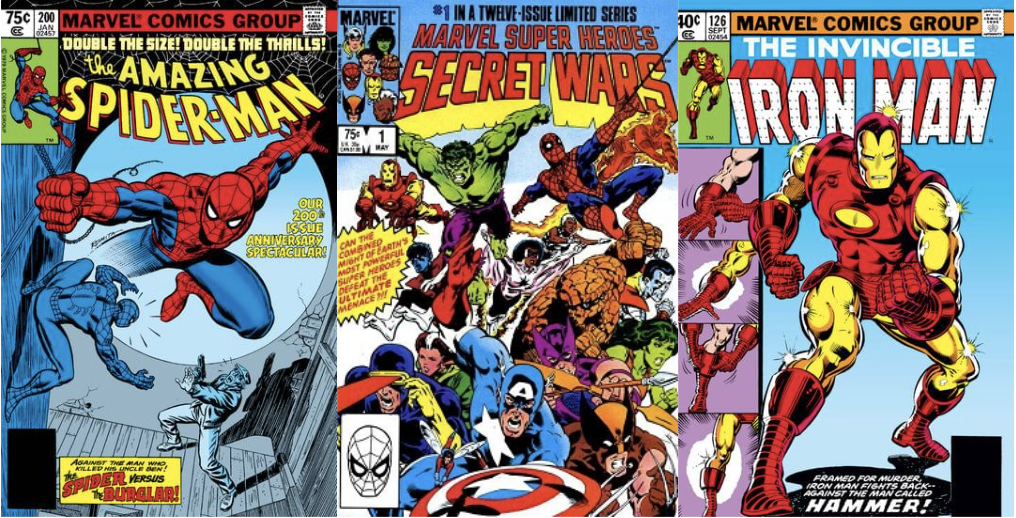

I was six years old when I pulled a reprint of “Amazing Spider-Man No. 1” from the rack at Michigan News, a rumpled newsstand at the heart of the city where I grew up. I still have the comic, dated April 1982; it’s tattered and almost worthless, but as a talisman it can transport me across time. Suddenly, I’m there. I’m shorter than the counter. The man at the register rings the sale. The world is vast and I’m unsure of how it works, but this comic is mine, and that’s enough.

As a kid I liked Spider-Man’s run-ins with colorful villains like Electro and Doctor Octopus, but the real draw for me was Spidey’s alter ego, the nerdy, scrawny Peter Parker. Every character in the comic thinks Peter is a frail high schooler who needs protecting; but as Spider-Man, he protects everybody. The perfect hero for a six year-old scaredy cat.

My mom says I was often sick as a baby. Ear infections, fevers, runny noses, the works. By preschool I was better, but in photos I’m all ribs, my arms are beggar-thin, my legs are broomsticks with knobs for knees. Scooby-Doo and Halloween Specials gave me nightmares. Hanging around my big brother and his friends, everyone was always older, smarter, faster, stronger. Naturally, I related to Peter Parker. Nevermind that he had real powers, and I had only the powerful imagination of a lonely kid.

Over time, I discovered comic books were everywhere. At the Waldenbooks and B. Dalton Booksellers of the area malls. In the periodical aisle at Meijer, the bright, sprawling supermarket where my mom shopped twice a month. At Harding’s, the tiny, five-aisle grocer near home. It was there that I picked up the fourth issue of Secret Wars, a limited series from 1984.

The gist of Secret Wars is this: a cosmic being called the Beyonder has kidnapped the galaxy’s greatest superheroes and villains and brought them to a distant planet to fight. The winners, the Beyonder says, will be granted anything their heart desires. The Beyonder’s godlike power troubles all the heroes, but none more than Thor, the Thunder God. In “Secret Wars No. 4,” Thor and another Asgardian debate their place in the cosmos given this new Beyonder. Who’s the real god here, they wonder, if they are not the mightiest ones?

Their conversation sent me spiraling. My family went to church every Sunday, sometimes twice, which is to say: I worried a lot about personal damnation. Was it blasphemous to own a comic with characters who claimed to be gods? How could it not be? I quickly regretted buying “Secret Wars No. 4.” But I couldn’t return it. I couldn’t give it away. So I ripped it to pieces, every page. Then I threw the scraps into the Where’s the Beef? wastebasket in my bedroom. Problem solved. Sort of.

My mom found the shredded comic book a few days later. Once a week she collected our wastebaskets and burned the paper in a brick-lined fire pit in the woods at the edge of our lawn. Why did you tear up your comic book? she asked, showing me the scraps. She wasn’t angry. She just didn’t understand. What was this boy doing? Why was he buying things just to destroy them? I don’t remember explaining myself. I probably didn’t know how. How does a child explain that pencil and ink drawings of imaginary people made him feel like his soul was in mortal danger?

2.

Some vintage comics are valuable simply because so few exist; say, the inaugural issue of Action Comics from 1939, which was the first comic to ever sell for more than $3 million. But most comics’ value is contingent on how well the physical book has been preserved: a tear, a water stain, a missing staple—all can render a comic virtually worthless.

I didn’t understand this as a kid. I treated my comics with the same utilitarian attitude that I applied to my friendships. One of my first friendships was built on a shared love of comics. Joel loved Iron Man like I loved Spidey. Together we pored over comic books as if they contained the key to understanding the adult world. I remember bringing a stack of Joel’s Iron Mans to the beach to read. He was sure I’d love them. I didn’t like Tony Stark nearly as much as Peter Parker, but I didn’t tell Joel.

Joel introduced me to Fanfare, a specialty comics shop located in a shopping center that was also home to the local skating rink. I’d never heard of a comics store before; I didn’t understand.

Like, they just sell comics? I asked. No newspapers?

But we never visited Fanfare together. I wonder if I had seen the shop, if I would have begun to see how old comic books could be objects of value. This was where our friendship began to diverge. One day at Joel’s house, I noticed a few of his Iron Mans were missing. I asked if he’d misplaced or loaned them out. Oh, no, he said. They’re in the freezer.

He had stowed the comics in a freezer below the stairs in his basement. Each of his comics had been lovingly slid into plastic comic book bags, presumably purchased from Fanfare. Joel assured me this was the proper way to store comics.

But how do you actually read them, I asked.

Joel and I got into a tiff after he caught me eating pizza while reading one of his cold storage comics. The grease will ruin the pages, he said. He wasn’t wrong. I wasn’t being careful. I still didn’t get it. If you couldn’t actually touch the comics that you owned, didn’t that defeat the purpose of buying them in the first place? I couldn’t imagine a future where the comics we bought with our quarters would one day be worth anything more than the price printed on the cover.

I would have quit comics as a teenager, except my brother Jeff gifted me an Amazing Spider-Man subscription. I no longer had to hunt for comics—they came to me in the mail in sleeves of plain brown paper. (Later, in college, I’d learn that porn also travels the mail under the cover of brown paper.) Shortly after the Spider-Man subscription began, a new artist named Todd MacFarlane began drawing the artwork. On the cover of “Amazing Spider-Man No. 298,” Spider-Man dodges the fiery fusillade of a villain named Chance. The drawing has an unusual sense of perspective and motion. The pages inside are also different, and not just the drawings. On page ten, Peter decides to surprise his wife Mary Jane by dressing up as a Chippendale dancer. Later, he promises her a “special dessert” in their bedroom.

In the next issue, No. 299, Mary Jane and Peter go dancing in Manhattan. She wears fishnets and a dress with a slit that almost reaches her waist. Her long red hair is permed and vampish, sort of like Elisabeth Shue in Cocktail (a movie I was not allowed to watch). At the end of the night they lie in bed; her head is on Peter’s chest, nothing risque, but there’s an adult undercurrent that even a naive boy could detect.

When I found issue No. 300 in the mailbox, it was heavier than previous issues because it had more pages. The story inside was longer in honor of Spider-Man’s 25th anniversary. And MacFarlane’s artwork? The kid gloves were off, along with other articles of clothing. On page 9, Mary Jane wears a nightie to answer the phone. On page 17, Peter sulks in their new apartment, so Mary Jane takes off her shirt, in what I can only assume is an attempt at consolation. It’s preposterous. And it blew my prepubescent mind. I was pretty sure if my parents read this comic, they’d confiscate it, cancel the subscription, and never let me read Spider-Man again. So I hid No. 300 in my closet—and waited for issue No. 301 to arrive.

MacFarlane drew Spider-Man for more than two years. He added melodrama to every page: flaring capes, wild explosions, frenetic fight scenes. But what I liked most was how he drew Mary Jane. Unfortunately, how she was drawn was pretty much all there was to her character: she was always either a damsel in distress or sexy wallpaper. The hormone-addled part of me was drawn to the peek-a-boo drawings of her; but as time passed, I grew increasingly aware that the writing wasn’t up to snuff. Flat dialogue and soapy storylines prevailed. Peter and MJ lose their lease! Peter goes back to school for his graduate degree! Mary Jane loses her contract as a model!

My Spider-Man subscription ran out when I was in eighth grade. I didn’t renew it. Though I’d spent half my life reading Spider-Man stories, I’d reached the end of the line. I stowed all the comics on a shelf in the closet but kept a poster of Spider-Man, a big and broody MacFarlane affair, on my bedroom door. Sophomore year, on a double date, I stopped by my house with three other people. They met my parents. They met our dog. They saw my room—and that’s when I saw with new eyes the Spider-Man poster on the door. The next time I stopped by the house with a date, the Spider-Man poster was gone.

3.

Growing up is a kind of exponential change. You bump along for ages, each day a lot like the last, same best friend, same favorite superhero, same bedroom at night, and the sameness gathers like a madness that you can’t shake until one day you notice something tiny, like how silly that Spider-Man poster looks, and so you make a change, just a little; and then something else happens, another change, bigger this time, you’re old enough to drive, you’re old enough to vote, then bang, bang, crash, pow, you’re an adult in New York City, you’re married to a woman you met at work, you’ve got two children, you’re in a vintage comics shop and the kids want funny books.

My daughter was ten and my son was six when we first visited Mysterious Time Machine, a tiny specialty shop located below street level on Sixth Avenue. Like most places in Greenwich Village, it was smaller than my childhood living room. My wife Raina helped our daughter locate a box full of Archies under a table. Meanwhile, I helped my son flip through Iron Man comics. When we got to the issues from the eighties, I couldn’t help but think about Joel.

We planned another trip to Mysterious Time Machine for Free Comic Book Day later that year. The kids were thrilled: Free comics! What could be better? Our plans were almost derailed by an email asking if my daughter was free for a playdate with an old pal. In the end, the girl’s dad agreed to meet us at the comics shop. At the shop, the dad was cheery and inquisitive; we chatted while our kids scampered around.

So this is all they sell, he said. Just comics?

Yeah, I said. I joked about looking for a graphic novel of a John Steinbeck classic for him. I joked because I was embarrassed. He was a journalist, a serious one, and I felt like I should have suggested we meet at the Morgan Library or the MOMA. But this was what I knew. This was what I grew up doing. It was a kind of heritage, however lowbrow. I mentioned that I still had some of the comics I collected as a kid.

Are they worth anything? he asked. Your old comics?

A logical question. We were standing in the middle of a comics shop, a place where vintage comics were trafficked. But I couldn’t answer it. I’d never seriously tried to find out. I tried to pass the question off as unknowable. But he was a serious man, and he was taking comics seriously. Why couldn’t I?

Last summer, I finally tried to answer his question. Our family spent three nights in a tricked out Airstream at a campground near Martha’s Vineyard. We cooked breakfast over an open fire and rented bikes, and at the end of the day we all re-watched Thor: Ragnarok, which my kids agree is one of the best Marvel movies.

One of their other favorites is Spider-Man: Far From Home. It’s a good flick, but not one of Marvel’s finest, if I’m honest, perhaps because the Spidey of the movie isn’t the Spidey I grew up with. He’s not nerdy enough; he’s not angry about his outsider status; he has actual friends. Maybe the idea of a stymied weakling who’s actually a superhero doesn’t have novelty anymore.

On the second day of the trip we drove to town for breakfast. Every cafe and pancake house had a waitlist. Raina reconoittored a nearby boulangerie while I brought the kids to Blast from the Past, a shop with vintage KISS action figures, WWF Pez dispensers, and Attack of the 50 Foot Woman posters. My teenage daughter ogled record players and vinyl album stacks. On our way out, we passed vintage comics in polyethylene bags on a display wall behind the front register. A familiar cover hung just over a clerk’s shoulder. Spider-Man, as drawn by Todd McFarlane; a copy of “Amazing Spider-Man No. 300.”

Hey, I have that comic, I said.

I hope you’re taking care of it, the clerk behind the register said. That’s when I noticed the asking price: $500.

A few days later, I brought down the box in my closet where I kept my old comics. A box I rarely opened. Inside, all the familiar faces were there. The Amazing Spider-Man reprints from 1982 and 1983. The wedding issue where Peter and Mary Jane get hitched. The six-part saga where Kraven the Hunter buries Spidey alive. And my copy of “Amazing Spider-Man No. 300.” I dandled No. 300 in front of Raina and the kids, as if keeping it for 33 years had been my plan all along.

If someone offered you $500, Raina asked, would you sell it?

I made a pained face. Is it crazy if I said no?

Later that August, all of us were in the car as I parallel parked in a space outside Sarge’s Comics in New London, Connecticut. Sarge’s is a large comics specialty shop located near the pier and across the street from the Yankee Peddler pawn shop and a wings ‘n pies restaurant.

Inside, the store was wide and deep. An armada of manga and Funko Pops filled space to the right. My daughter lost herself in a happy maze of imported books from Japan. My son and I wandered the aisles until we encountered a man in a black t-shirt who resembled an employee. He was performing touch-up surgery on a furry monster head, likely something for the display window.

If you found what you want, he said, someone can ring you up over there.

He barely looked up. But when he did, I pointed at my son, who was holding three Spider-Man comics, including No. 300.

These are some of my dad’s old comics, he began. We wanted to know—

Sorry, the clerk said, interrupting. We don’t do appraisals.

My son looked at me, uncertain.

You can still help, I said, careful to sound chipper. We don’t need a formal appraisal. We’re wondering if you think it’s in good enough condition to be worth anything?

The clerk took No. 300, turned it over, frowned, then handed it back. I really couldn’t tell you, he said. The owner’s the one who handles comics. I manage everything else.

I was tempted to ask what this place was for except comics, really? But I didn’t. I thanked him for his time and we went back to browsing. Board games, figurines in glass cases, vintage comics in bankers boxes: before long, my son found something exciting. The world is vast and he has a long way to go before he tires of it. For my part, I also felt lighter, happier. It wasn’t till we were back in the car that I realized why: because I didn’t get an answer. I didn’t have any clearer idea of what these comics were worth. I didn’t have to decide whether to sell or not to sell. Because what was it worth to me? Hard to say. Maybe impossible.

I am now further from that boy in Michigan News than the boy in Michigan News in 1982 was from the very first Amazing Spider-Man comic in 1963. That six year-old boy was wide-eyed for funny books drawn almost 20 years earlier; the man that I am now is 40 years older than the boy I was back then. Twice the distance, and growing every day. How many more decades will the game keep playing out? How long will I carry with me a box of worn comics, of tattered memories? For what price would I ever let go a part of me?