Ada Limón was always going to be an artist. “I love the idea of making things, creating things, performing things,” she says via Zoom from her home in Lexington, Ky., where she’s lived for the past decade with her husband, Lucas Marquardt, a horse racing reporter. Her office’s door is closed until the relentless pawing of their ancient cat (“I think we’ve figured out she’s 21”) forces her to hop up and let the animal in. “My undergraduate degree is in drama, and for a long time, I thought that my career would either be on the stage or behind the stage, in some way. I was also a dance minor. I was very much the person who was into all the performing arts. It wasn’t until my junior year, when I was not allowed to take any more performing arts electives, because I had taken them all, that I took my first poetry class. And from the minute I took it, I was like, I’m in love with this. This is exactly what I wanted to do.”

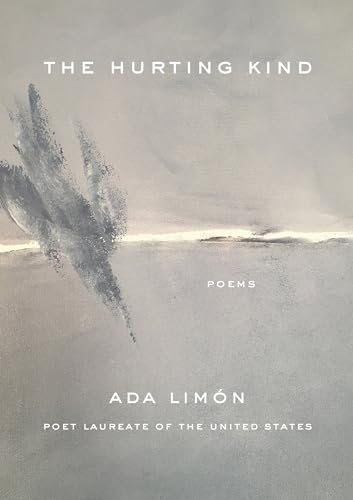

That class was providence, as Limón, 46, is now one of America’s preeminent poets, and her prominence is only growing—as is her prolificacy. Last September, Milkweed Editions, Limón’s longtime publisher, announced a three-book deal with her brokered by Rob McQuilkin at Massie & McQuilkin. The titles acquired include Beast: An Anthology of Animal Poems, which Limón will edit, and which is set to be released in 2024; a volume of new and selected poems due in 2025; and The Hurting Kind, her latest, which will hit shelves in May.

Previously, Limón had published five collections, the last three of them with Milkweed. Two of those titles attracted the attention of nearly all of the country’s major literary awards bodies. In 2015, her collection Bright Dead Things was a finalist for the National Book Award for poetry, while her following book, The Carrying, won the 2018 National Book Critics Circle Award and was shortlisted for the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award in 2019. Both of those books received widespread acclaim. In a starred review, Publishers Weekly called The Carrying “gorgeous, thought-provoking,” and a “fearless collection.” And last year, Limón was tapped to host The Slowdown podcast, a collaboration between American Public Media and the Poetry Foundation, for its third season, succeeding U.S. poet laureate Tracy K. Smith.

It’s not just the artistic establishment that has embraced Limón’s work. The two aforementioned collections have sold more than 55,000 print copies combined, according to NPD BookScan—a remarkable feat in a literary form long considered a commercial black hole. Perhaps Limón herself would ascribe her books’ success to a resurgence in appreciation for the form. “For all its faults, I think that social media has actually done one wonderful thing for poetry…and in many, many ways allow for poetry to become completely accessible to anyone,” she told CNN last October. “It is an amazing time to be alive in the world of poetry.”

But Daniel Slager, Limón’s editor and Milkweed’s publisher and CEO, sees Limón’s success as an extension of her particular gift. “In the poetry world, the whole notion of being approachable or readable can be a curse,” he says, “because it’s often thought to be antithetical to sophistication artistically—a stupid dichotomy, really, although at times there’s something to it. But she just transcends that, in such a beautiful way, with so much integrity. Poets’ poets love her, and people who don’t read that much poetry love her. I think that’s so remarkable.” Also remarkable, Slager notes, is that her next book is, to his mind, her best yet: “It’s not that common for writers that each book is better, but that’s been the case with Ada.”

The Hurting Kind exhibits all of the lyrical and thematic hallmarks of Limón’s poetry: deft narrative, elegant poetic structure, and attunement with and appreciation for the natural world. The book is separated into four sections, each named after one of the seasons of the year, and showcases its author’s deep understanding and questioning both of the nature of human interconnectedness, and of loss. Still, the book represents, in some sense, a break from Limón’s prior work—or at least the narrative around it.

“One of the things that happened with The Carrying, which is totally understandable, was that it had a lot of narrative around it—it had a tagline,” Limón says. While that book dealt plainly with her struggles with vertigo and with conceiving a child, she did not think that the pain those poems conveyed would dominate its critical reception so decidedly. “‘A woman struggling with infertility’—every review started with that,” she recalls. “I think that part of the joy of making this book was finding out what it is to push against some of that, to write with a kind of abandon, without pinpointing a specific narrative of a life that can be summed up.”

In that light, The Hurting Kind’s first poem, “Give Me This,” could be seen almost as a mission statement. Her recent work, she explains, is “urgently set on speaking from the me that is both the speaker and the author.” “Give Me This” does just that, with the speaker describing an experience of Limón’s watching a groundhog “waddle-thieving my tomatoes still/ green in the morning’s shade” and “taking such pleasure in the watery bites.” The poem asks, “Why am I not allowed delight?”—a question likely relatable to anyone reading poetry in a world enduring a global pandemic and facing heightened global strife and an ever-worsening climate disaster.

McQuilkin, Limón’s agent, found that sentiment particularly powerful when he first read the collection, in spring 2021. “I remember getting very excited about what role the book could play out there, in these times, that are in so many ways bleak,” he says. “Somehow, things feel a little less bleak when you’re reading Ada, because she finds the contours of what is real, and beautiful, even when things are not perfect or complete.”

In the end, the speaker of “Give Me This” allows herself that delight, becoming one, in a way, with the intruding rodent:

I watch the groundhog more closely and a sound escapes

me, a small spasm of joy I did not imagine

when I woke. She is a funny creature and earnest,

and she is doing what she can to survive.

The poem is “a little, tiny rebellion,” Limón explains. “It’s like, ‘I’m gonna watch this freakin’ groundhog and I’m not going to tell you my thoughts on suffering’—even though, of course, this book is full of joy and grief both, and life.”

It is a rebellion, too, against lyric poetry’s more lachrymose tendencies, which Limón admits are easy to lean into. “I always tell my students that one of the hardest poems to write is a happy poem,” she says. “Try to write a contented poem and see what happens. It’s really, really hard! But what is it to represent life as a whole thing, as opposed to an easy or fixed narrative?”

The book’s rebellions are multifold. Another is in its poems of family. “I remember sitting with some older poets in the summer of 2001, and they were telling me that I couldn’t write all these family poems—that I couldn’t have grandmother poems, and I couldn’t have grandfather poems, and brother poems,” Limón says. “‘It’s too juvenile,’ they said. ‘It’s too tender.’ So I denied myself that, because I was told that that wasn’t what you were supposed to do. But so much of who I am, as a person, is in honor and in service of my relationships. And with this book, I was like, You know what? I’m 45, and I get to write whatever poems I want. And what I want to write are poems that say the word grandmother 1,000 times.”

Here, they practically do. One section of the book’s title poem concludes: “…my grandmother,/ (yes, I said it, grandmother, grandmother) leans to me and says,/ ‘Now teach me poetry.’”

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.