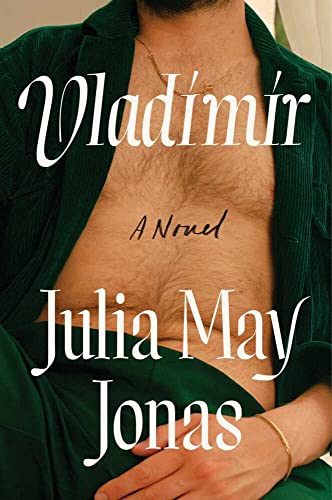

In her debut novel, Vladimir, playwright Julia May Jonas turns her eye to shifting social mores and the tensions they cause between different social groups by employing a classic trope: the affair (both intermarital and intergenerational) on the college campus.

Publishers Weekly called Vladimir “a mordantly funny post-#MeToo campus story about a 50-something woman unhinged by desire for a younger man.” The book, released earlier this month from Avid Reader, finds its unnamed narrator attempting to come to grips with both her lust for a talented new colleague and increasing scrutiny on her own actions from colleagues and students alike, as her husband, who is also the head of their department, is under investigation after being accused of sexual predation by a number of former students.

The result is a page-turner blending romance with social observation that speaks to issues of consent, desire, and trauma in an era in which generational and political divides both on and off campus seem to be ever-widening.

The Millions spoke with Jonas about the campus novel as social novel, what romantic affairs and their aftermaths still have to teach us about human nature, and how she brought her experience as a playwright to bear on writing a first-person novel.

The Millions: What made you decide to center this narrative on affairs between colleagues, and between teachers and students?

Julia May Jonas: I think that affairs, and how we respond to sexuality, is still kind of a litmus test for where we are emotionally, and I think it’s shifted. It continues to shift. But no matter what structures we’re interacting with, I think love is still something that we’re all interacting with all the time. The book for me was a big question about desire inside of this woman, and her being torn about what she wants and what she’s allowed to want and can choose to want and how she is supposed to react to desire.

TM: The narrator seems to believe she’s weighing nearly every angle she could on a certain situation, and yet when she acts, it’s in line with her pre-existing biases. Academics tend to be very analytical in their assessment of things, as the narrator is, but even the very analytical miss things. How do you write a character like that?

JMJ: Partly what allowed for that was a sense, when I was writing, of something that came from being a playwright. The writing process really came out almost as an extremely long monologue. She’s working these things out for an audience, in a way. And whenever you’re working something out for an audience, you’re consistently making choices—about what you’re allowing and you’re admitting and what you’re not allowing and what you’re not admitting.

TM: Which the author is doing as much as the narrator is, right?

JMJ: Of course! And that’s when it helped for me to really situate myself inside of her voice. When I do that, and when I’m thinking through her voice, and I’m thinking about her talking to someone or telling someone, that I felt like I could work through what she would say, what she wouldn’t say, what she would see, what she didn’t see.

TM: Did the decision to go with first person narration come specifically from the theatrical tradition?

JMJ: I had actually started out the book with a couple chapters in first person, and then I switched perspective, and I had it in third person, focusing on Vladimir and his perspective. In the end, I felt like this was about someone’s fantasy, and their desire to make their fantasy a reality—and how that pushes the book itself into a fantasy. It became clear to me that the force was going to come from staying inside of her head for the for the entire time.

TM: Was that a more natural writing process for you as well?

JMJ: It was certainly the natural process for this book. I think there were, because this is my debut, things I was figuring out about writing prose as I was writing it. And I think there would have been a different set of things that I was figuring out about writing prose if I were writing in the third person.

TM: How did you bring your experience with a small liberal arts college and this particular generation of students’ perspective on social issues to bear on this novel in a way that informed it but left it open to interpretation?

JM: Well, for one, I am not tenured. I am not a professor. I am a teacher, and a guest artist and lecturer at a small liberal arts college. I am in, but not of, college life. And so I’ve been able to kind of sit to the side and see it, rather than be inside of it. I’m also 20 years younger than my protagonist. That’s kind of crucial, because what I was most interested in—what I’m always interested in—are people who, all of a sudden, find the ground shifted from beneath them. Here you have somebody who is a liberal woman; who has deemed herself to be, in her mind, on the right side of history; who has seen herself as being always an advocate for her students; who has not had to question what she feels about things; and who has had a particular relationship to sexual politics for both herself as a woman, and also in terms of her students. And now she is dealing with the ground shifting from underneath her. That is the thing that I found most interesting. That’s certainly something I observe, to greater and lesser extents with my professors around me at Skidmore College. (Disclosure: the writer of this piece is a graduate of Skidmore College.)

I love my students and have great relationships with them. And I think they’re right. I think what I was interested in is someone’s perspective of thinking, “Wait, I thought it was this way, and now it’s this way. I thought I was this kind of person, and now I’m this kind of person.” That, to me, is the most fascinating question about her. That’s what I’m always most interested in, is what these people do in these circumstances. And I think John, her husband, thinks he was one kind of person, and then finds that he’s another kind of person.

TM: Because what kind of person you are isn’t set in stone, it’s determined by social mores that are ever-shifting?

JMJ: Exactly. And I’m 20 years younger than my protagonist, but when I went to college, it was kind of a cool and sexy thing to date your professor. And it keeps shifting. I think it shifts even more now because of our ability to chart the shifts. It’s shifting faster and faster.

TM: Do you think it is possible, in 2022, for a campus novel to not also be a social novel?

JMJ: I don’t know when a campus novel was not a social novel. I think the idea of all campus novels are that colleges are kind of test tubes for life, constructed realities in which people who are transitioning from being children to adulthood are put in a small society.

TM: And yet there are campus novels so intensely focused on the interiority of their protagonist or subject that the social aspect is somewhat blurred by character. That didn’t strike me as being the case with this novel.

JMJ: It’s interesting that you bring up the idea of interiority, because I think the book is, in itself, about interiority, and the force of the narrator’s perspective and how it colors our perspective as we move through the book. Vladimir is, for her, this object, that becomes a kind of icon, in a way, that she can put her energy toward and build up fantasies around, and that she can filter through everything that she is processing at that moment, whether she is aware of it or not. In some cases, she is aware of it. And there are a lot of things she’s not aware of, in terms of why she’s feeling this pull toward this other person.

TM: There is one moment in the novel that really highlights this shifting of mores, in which the narrator notes how impressed she is by the students’ advocacy for themselves, because she and her generation, always assumed that there were certain things that would never change.

JMJ: I think it’s kind of an American phenomenon, in terms of how hard it is for someone to endure any hardship and not turn around and say to the next person, ‘And now you should endure hardship, too.’ I think that’s kind of endemic in so many issues that we have right now. It’s so challenging for people to go through something and then not say, “Well, why can’t you go through that too? I went through it!” Instead of wanting to shift the world in some way.

TM: Yet the students don’t seem to feel that way. John’s former students, who attempt to have him removed from his position as chair of the English department, are in effect saying, “I went through this, and I don’t want anybody to ever have to go through this again, which is why I want this this professor removed.” How do those two imperatives coexist in the book?

JMJ: I’m not sure they do. One time, my friend said to me, “It feels like there’s two camps right now. There’s the camp that says, ‘your trauma shouldn’t mean anything, get over it, keep moving.’ And then there’s another camp that says, ‘your trauma should mean everything, and anything can be categorized as trauma.'”

TM: Where does a campus culture, which eventually transports itself to culture at large, go with such disparate assessments of what an incredibly important word like trauma even means?

JMJ: Well, my hope is that the book doesn’t offer a take on that. I don’t have a take on that, necessarily. I have lots of questions about that. I hope that it’s more about describing what various factions and camps are feeling and putting forth and what the opinions are than it is about taking a stance on any of it.

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly.