A few years ago, I became unexpectedly obsessed with mushrooms. It started, as so many unlikely obsessions do, with research for a novel. I didn’t need to know much about the world of fungi to write the scenes I had in mind, but the more I read about mushrooms, the more I wanted to know. I began to see them everywhere: popping up from the mulch of street trees, crouched at the sides of buildings, and creeping across rotting park benches. I was living in Brooklyn at the time, where nature felt scarce and paved-over, but suddenly my eyes were drawn to vacant lots, construction sites, and the narrow strips of unclaimed land between buildings. Where I once might have focused on the unsightly pieces of trash and felt depressed about microplastics and chemicals in the soil, I was more inclined to lift a soggy piece of cardboard to see what was growing underneath it. Even though nothing had changed, New York City became more alive to me, and I became a little bit happier in my day-to-day life.

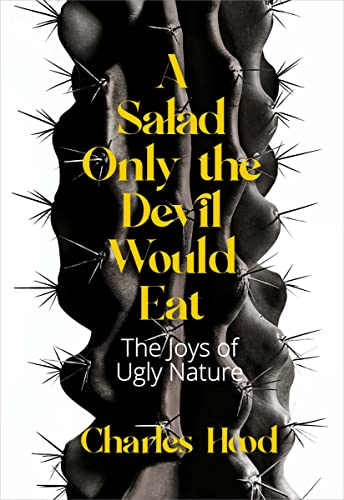

Looking for mushrooms in rotting park infrastructure is what Charles Hood would call, “the joys of ugly nature.” His debut essay collection, A Salad Only the Devil Would Eat, is a book that celebrates the nature that we can access every day in our own backyards—and if we don’t have backyards, then in a parking lot, garbage dump, or whatever scarred, imperfect spots are nearby. Writing from his home in Palmdale, Calif., Hood has learned to embrace a landscape that he describes as “sections of creosote edgeland that collectively are not quite original desert, not quite exurban wasteland, but an in-between zone of once-grazed, sometimes-trash-filled, always fascinating possibility.” Hood acknowledges that for most people, this area looks like it “has been hit about ten times with the ugly stick and left for dead,” but his ongoing thesis, which he returns to throughout his essays, is that our vision has been clouded by fantasies of empty, pristine wilderness and nature writing that “too often drifts into High Church rhetoric.” Hood’s own writing is a tonic, full of specific, weird details. If find yourself consulting a dictionary as you read, it’s because Hood is a widely published poet, and brings a poet’s magpie vocabulary to his prose. The title of his collection comes from his assessment of his local plant list: bitterbrush, burro weed, creosote, jumping cholla and Mormon tea, i.e. “a salad only the devil would eat.”

Everything I’ve quoted from in the above paragraph comes from Hood’s opening essay, “I Heart Ugly Nature,” a witty meditation that sets the stage for the 13 essays that follow. Hood’s conversational, personal writing examines his obsessive-compulsive relationship with bird lists, his addiction to field guides, his mixed feelings about taxidermy and zoos, his awe of whales, and his love of pine trees, palm trees, and penguins. A handful of pieces are more journalistic in tone, delving into the history of Los Angeles’s water supply, Aububon’s Birds of America, and the red dye that is harvested from cochineal, a parasite that grows on the prickly pear cactus and “make the cactus pads look like they have been spackled with crusty toothpaste.” I learned a lot reading these essays, but in an offhand way. It’s a book that celebrates the delights of amateurism, the facts that you stumble upon when you’re reading for something else, or the rare bird you happen to notice when you’re out on a whale watch.

Everything I’ve quoted from in the above paragraph comes from Hood’s opening essay, “I Heart Ugly Nature,” a witty meditation that sets the stage for the 13 essays that follow. Hood’s conversational, personal writing examines his obsessive-compulsive relationship with bird lists, his addiction to field guides, his mixed feelings about taxidermy and zoos, his awe of whales, and his love of pine trees, palm trees, and penguins. A handful of pieces are more journalistic in tone, delving into the history of Los Angeles’s water supply, Aububon’s Birds of America, and the red dye that is harvested from cochineal, a parasite that grows on the prickly pear cactus and “make the cactus pads look like they have been spackled with crusty toothpaste.” I learned a lot reading these essays, but in an offhand way. It’s a book that celebrates the delights of amateurism, the facts that you stumble upon when you’re reading for something else, or the rare bird you happen to notice when you’re out on a whale watch.

Embracing contradiction is an important part of Hood’s credo, and a theme he revisits often. In his essay, “Love and Sex in Natural History Dioramas,” he admits that he loves dioramas even as they obscure reality, observing that there are never any pieces of trash in a diorama, or airplane contrails in the painted sky; the only evidence of human influence is that fact that the animals are arranged with the male animal cast as protector, in order to present a narrative that is pleasing and familiar to visitors. “They [dioramas] are useful, attractive, artistic, but also colonial and limiting and laden with daddy issues.” Another contradiction Hood leans into is his love of list-making, a hobby that is both second nature and “darkly addictive.” He has to quit his bird list because it was taking the fun out of hiking: “Too often I came back from a trip unhappy over something stupid—like not seeing the suchity-such, which Joe Money-Wad had seen only a month earlier. Never mind all the other things I had seen.” Instead of birds, Hood now counts mammals, a hobby that takes him all over the world to collect sightings. Does he feel guilty over his carbon footprint? Oh, yes, but at the very same time he relishes his adventures, and feels pride for his mammal list, which is creeping up to 1,000.

There are writers who would dwell in their climate anxiety for a beat longer than Hood does, and I couldn’t decide if I minded that he didn’t. Mostly, I felt relieved. Over the past decade, I’ve read many books and articles that detail the current climate crisis, and while I think it’s important to know the extent of the damage, and to investigate strategies for repair and restoration, we also need writing that looks for the bits of joy amidst the profound losses. It’s crucial, of course, that Hood is honest about what has been destroyed. If he reaches for optimism, it’s only for his own sanity, not because he’s in denial. In “Fifty Dreams for Forty Monkeys,” an essay about the futility of wildlife management (among other things) Hood writes about the necessity of accepting nature as it exists in reality: “Because the thing is, I live when I live, and while I can yearn for the passenger pigeon or the truly stupendous and entirely extinct Carolina parakeet, that won’t help get me through the day. I have to love what the day allows me to love.”

Maybe the difference between Hood and journalists like Elizabeth Kolbert, Bill McKibben, and David Wallace-Wells, whose recent books Under a White Sky, Falter, and The Uninhabitable Earth anticipate future catastrophes, is that Hood stays very much in the present, looking at what animals and plants are doing now to cope with the changes at hand. He’s not particularly interested in technological or political solutions that humans might employ to deal with the climate crisis and believes that “our best action on behalf of nature may be inaction: stand back and let it do its thing, see what happens.” Investigative journalist Cal Flyn makes similar insights in her recent book, Islands of Abandonment: Life in the Post-Human Landscape, which looks at the way that nature has rebounded in toxic spaces abandoned by humans, such as the exclusion zone in Chernobyl, and Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island. Her reporting backs up many of Hood’s casual observations about the hidden virtues of “ugly nature” and the folly of human interventions. I don’t mean to suggest that either writer recommends that we continue to burn fossil fuels or destroy wildlife, only that both writers observe how nature can thrive when left unbothered.

Maybe the difference between Hood and journalists like Elizabeth Kolbert, Bill McKibben, and David Wallace-Wells, whose recent books Under a White Sky, Falter, and The Uninhabitable Earth anticipate future catastrophes, is that Hood stays very much in the present, looking at what animals and plants are doing now to cope with the changes at hand. He’s not particularly interested in technological or political solutions that humans might employ to deal with the climate crisis and believes that “our best action on behalf of nature may be inaction: stand back and let it do its thing, see what happens.” Investigative journalist Cal Flyn makes similar insights in her recent book, Islands of Abandonment: Life in the Post-Human Landscape, which looks at the way that nature has rebounded in toxic spaces abandoned by humans, such as the exclusion zone in Chernobyl, and Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island. Her reporting backs up many of Hood’s casual observations about the hidden virtues of “ugly nature” and the folly of human interventions. I don’t mean to suggest that either writer recommends that we continue to burn fossil fuels or destroy wildlife, only that both writers observe how nature can thrive when left unbothered.

I suspect that off the page, Hood is a lot more pessimistic, but in his writing, he’s trying to keep the darkness at bay. He also tries to keep the human perspective at bay, nudging us to remember that it’s just one point of view, among many. One of my favorite throwaway lines in this collection comes after Hood shares the pet names that zookeepers gave to four captured penguins: Mo, Smo, Andy, and Mandy. Another writer might have commented on the inanity of the nicknames. Instead, Hood observes, “what the penguins named the keepers, we do not know.”

I suspect that off the page, Hood is a lot more pessimistic, but in his writing, he’s trying to keep the darkness at bay. He also tries to keep the human perspective at bay, nudging us to remember that it’s just one point of view, among many. One of my favorite throwaway lines in this collection comes after Hood shares the pet names that zookeepers gave to four captured penguins: Mo, Smo, Andy, and Mandy. Another writer might have commented on the inanity of the nicknames. Instead, Hood observes, “what the penguins named the keepers, we do not know.”