I first met poet Maggie Smith when we were both in residence at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. I was born and raised in the Midwest and tend to seek out fellow Midwesterners—I would say more than half of my New York writer friends are actually originally from the Midwest—and at a resident reading I saw her casually drinking beer straight from the bottle, which reified my judgment, even before I learned she was from Ohio. Her poetry also had that straightforwardness, say of a neighbor you really like who is both kind and an astrophysicist. Smith’s poems refuse to show off, can be brilliant by combining familiar objects from a landscape tinged with nostalgia for childhood, and use Twitter as a springboard all at the same time.

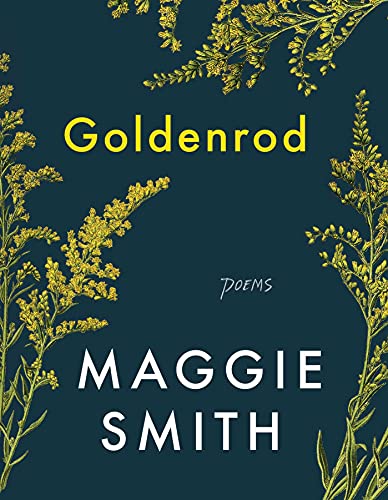

However, poetry tends not to take up much space in our cultural landscape, especially during the last few years, which have been dominated by the simplistic rhetoric of divisiveness and bombast. Perhaps, then, it was not such a surprise to see her 2016 poem “Good Bones,” (published in Waxwings, then in the collection of the same name in 2017) suddenly appear on a an episode of Madam Secretary in 2017, as if such an assault on language and sensibility engendered an equally strong counterpunch. Her newest collection, Goldenrod, was just released

The Millions: Can you tell me about your collections of poetry?

Maggie Smith : Goldenrod (2021), my fifth book and my fourth collection of poems, in the words of poet Ellen Bass, “brims with a fervent love for this gorgeous and wounded world.” These poems celebrate the present moment, and the ways we seek—and find, again and again—the extraordinary in our ordinary lives.

Good Bones (2017) My third collection of poems about motherhood, memory, and finding light in the darkness. The titular poem was published online the week of the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando and the murder of MP Jo Cox in England, and went viral internationally. Now I call that poem my “disaster barometer:” whenever tragedy strikes somewhere, it is shared widely.

Good Bones (2017) My third collection of poems about motherhood, memory, and finding light in the darkness. The titular poem was published online the week of the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando and the murder of MP Jo Cox in England, and went viral internationally. Now I call that poem my “disaster barometer:” whenever tragedy strikes somewhere, it is shared widely.

The Well Speaks of Its Own Poison (2015) Ten years passed between the publication of my first and second books. I point this out to reassure writers who are worried about their productivity and their trajectory. Some books take longer to write. Some books take longer to find the right home. Here’s to tenacity and patience.

The Well Speaks of Its Own Poison (2015) Ten years passed between the publication of my first and second books. I point this out to reassure writers who are worried about their productivity and their trajectory. Some books take longer to write. Some books take longer to find the right home. Here’s to tenacity and patience.

Lamp of the Body (2005) My first book, which began as my MFA thesis, won the Benjamin Saltman Award. I wrote these poems in my early- to mid-20s, and it’s fascinating to look back on them and see the seeds of poems that would grow later.

Lamp of the Body (2005) My first book, which began as my MFA thesis, won the Benjamin Saltman Award. I wrote these poems in my early- to mid-20s, and it’s fascinating to look back on them and see the seeds of poems that would grow later.

My first book of prose, Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change, was published in 2020 and to my surprise became a national bestseller. It’s a collection of essays and quotes (I call them notes-to-self) about reimagining your life—and yourself—when faced with difficult changes.

My first book of prose, Keep Moving: Notes on Loss, Creativity, and Change, was published in 2020 and to my surprise became a national bestseller. It’s a collection of essays and quotes (I call them notes-to-self) about reimagining your life—and yourself—when faced with difficult changes.

When we met at VCCA in 2011, I was working on poems for The Well Speaks of Its Own Poison, but it was there that I also began writing poems that would appear in Good Bones. I met Baltimore-based paper artist Katherine Fahey there and began writing a series of poems inspired by her work, and I think of that series of poems as the structure for Good Bones. Those poems are the load-bearing beams in the book. (A quick plug for writing residencies: the artistic cross-pollination and friendships made at places like VCCA can be magical.)

TM: How did you “decide” you wanted to become a poet and who are some of your influences?

MS: I don’t think I ever “decided” to be a poet—I just started writing poems and never stopped. If you write poems, you’re a poet; whether you try to make some sort of career from writing is a different thing entirely. I began writing as a teenager, as many of us do, probably because it’s a time of questioning and testing boundaries and learning about yourself. The first books of poems I owned and read were by Marge Piercy, Sylvia Plath, Diane DiPrima, Donald Hall, Nikki Giovanni, Anne Sexton, and Robert Hass. I gravitated toward poems with apt metaphors, poems that described things, places, and feelings in ways I could not quite articulate myself. I still do.

TM: Do you write prose?

MS: I do! Keep Moving is prose—quotes interwoven with essays that are lyrical, rooted in metaphor, and relatively brief. They’re the essays of a poet. I’m working on some longer-form prose projects, too, and that has been an invigorating challenge. Even my poems tend to be on the shorter side, so I’m enjoying stretching myself across multiple pages, experimenting with pattern and structure, and resisting the sonnet-lover’s urge to invite the reader into the room and then quickly shuffle them out the door. I’m like, “No, please, sit down, get comfortable, stay a while!”

TM: Walt Whitman aside, it’s rare in America to have a poet become a cultural figure — I’m not counting Amanda Gorman because her career is just starting. Since I’ve known you, you were a poet who’d beaten the odds by getting published—I don’t think non-poets realize how difficult it is to get a poetry collection published. Then your poem “Good Bones” became truly a cultural phenomenon, as did Keep Moving, which is in a totally different vein. What was that like? Did it feel at all like a natural evolution of the work you were doing—or?

MS: Keep Moving does feel like part of a continued conversation I’ve been having with readers—and with myself, on the page. Each book—each poem, easy essay—is different from the previous one, but I do think there are more similarities than differences. I can look back through the five books, four poetry and one prose, and see similarities between them, because they’re mine. I see thematic overlap: memory, family, how we know what we know, how language sometimes fails us, how we find beauty in a broken world. I see craft elements repeating as well: metaphor, imagery, attention to rhythm and sound in the word choices and syntax.

TM: How do poets make a living, especially if they have families?

MS: Most of the poets I know also do something else: they teach, they work in publishing, they freelance as writers or editors. Some work in healthcare or tech. After my MFA, I worked in children’s book and educational publishing for years, before striking out on my own as a freelancer in 2011. I’ve been self-employed for the last 10 years, cobbling together a professional life from writing, teaching, editing, copyediting, and traveling for readings, workshops, and speaking engagements. No two days are the same. What I gave up in stability (and benefits) I gained in freedom and flexibility, and to this point the trade-off has been worth it. I have so much more time with my children because I make my own schedule.

TM: You have a new collection, Goldenrod. Has your new fame put undue pressure on creating something legible to a larger public? Do you feel different (or have to shield yourself) from the idea that people are looking at you, when your job is more to be an observer?

MS: After “Good Bones” went viral, I had a (thankfully brief) crisis: How do I write the next poem? Are people expecting poems like that from me now? As a poet, I’d felt very free from the idea of audience expectations up to that point—and frankly, free from the idea of much of an audience at all. Poetry has a relatively small but discerning and loyal readership compared to, say, fiction. But I knew I would not—could not, and didn’t want to—write another “Good Bones.” I joked that there would be no sequel, no “Better Bones” or “Good Bones 2: This Time It’s Personal.” In order to keep making poems, I have to tune out the static that comes from the outside world—both negative and positive noise. I need to be able to have a quiet, focused conversation with myself on the page. Goldenrod is a book that came from a place of stillness and observation. It’s hard to encapsulate what a collection of poems is “about,” but many of these poems are about seeing the world around you more clearly.

TM: What poet living or dead have I probably not heard about but should read?

MS: I don’t want to assume anything about your reading habits! You seem to be someone who reads widely and has eclectic taste. I bet you’ve read poems by some of my favorite living poets—Carrie Fountain, Vievee Francis, Victoria Chang, Natalie Shapero, Michael Bazzett, Catherine Pierce, Jericho Brown, Ellen Bass, Caroline Bird, and so many others. But there are certainly some poets who deserve a wider readership, and someone who comes to mind is the terrific Eloisa Amezcua. Her first book, From the Inside Quietly, is gorgeous. I’m really looking forward to her next book, Fighting Is Like a Wife, which portrays boxer Bobby Chacon and his wife, Valerie, and is due out in spring 2022.

MS: I don’t want to assume anything about your reading habits! You seem to be someone who reads widely and has eclectic taste. I bet you’ve read poems by some of my favorite living poets—Carrie Fountain, Vievee Francis, Victoria Chang, Natalie Shapero, Michael Bazzett, Catherine Pierce, Jericho Brown, Ellen Bass, Caroline Bird, and so many others. But there are certainly some poets who deserve a wider readership, and someone who comes to mind is the terrific Eloisa Amezcua. Her first book, From the Inside Quietly, is gorgeous. I’m really looking forward to her next book, Fighting Is Like a Wife, which portrays boxer Bobby Chacon and his wife, Valerie, and is due out in spring 2022.