As both a daily reader and somewhat frequent contributor, I have long been a devotee of The Millions. In the last several years, I have also become an Ed Simon devotee. Ed’s articles in The Millions are not only fresh and surprising, they are also always about something I had no idea I needed to know. Simon is an intellectual omnivore; his essays cover an awe-inspiring range of topics.

So, I was delighted to read Simon’s quirky, wonderful, and informative new book, An Alternative History of Pittsburgh. At 182 pages, this 5” by 7” volume reads like a microcosm of American history, warts and all. The book is composed in short chapters, largely chronological, that read as both love letter to Simon’s hometown and an effort to reckon with Pittsburgh’s past—the good, the bad, and the ugly. From Socrates to August Wilson, from Uruguayan historian Eduardo Galeano (whose Open Veins of Latin America is a classic on the deleterious impacts of America ravaging Latin America) to Andrew Carnegie’s rapaciousness, to Pittsburgh’s role as an early American frontier town, to Billy Strayhorn, Major League Baseball, and so much more, An Alternative History of Pittsburgh contains gems on every page.

So, I was delighted to read Simon’s quirky, wonderful, and informative new book, An Alternative History of Pittsburgh. At 182 pages, this 5” by 7” volume reads like a microcosm of American history, warts and all. The book is composed in short chapters, largely chronological, that read as both love letter to Simon’s hometown and an effort to reckon with Pittsburgh’s past—the good, the bad, and the ugly. From Socrates to August Wilson, from Uruguayan historian Eduardo Galeano (whose Open Veins of Latin America is a classic on the deleterious impacts of America ravaging Latin America) to Andrew Carnegie’s rapaciousness, to Pittsburgh’s role as an early American frontier town, to Billy Strayhorn, Major League Baseball, and so much more, An Alternative History of Pittsburgh contains gems on every page.

The book starts in 300 million BCE with a dive into the geologic characteristics that make Pittsburgh unique, and ends in 1985 with the collapse of Pittsburgh’s legendary steel industry due to globalization. In its overarching sweep, coupled with its specificity to place, this book called to mind Tiya Miles’s eye-opening The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits.

The book starts in 300 million BCE with a dive into the geologic characteristics that make Pittsburgh unique, and ends in 1985 with the collapse of Pittsburgh’s legendary steel industry due to globalization. In its overarching sweep, coupled with its specificity to place, this book called to mind Tiya Miles’s eye-opening The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits.

Simon sums up his feelings about Pittsburgh toward the end of book: “It must be admitted that the place is almost preternaturally charged with a broken beauty, a tinge of the numinous throughout the landscape itself.”

I was excited to catch up with Simon by email.

Martha Anne Toll: How did you come to the subject of Pittsburgh, other than growing up there?

Ed Simon: I’d always wanted to write a Pittsburgh book. When I was an undergraduate at Washington and Jefferson, I tinkered at a super-pretentious Pynchonesque exercise of a novel that I titled Fourteenth Ward, and that I imagine is still in a box in my mother’s basement. I rightly abandoned it, but I wonder if this new, slim volume is an attempt to do what I couldn’t do with that novel, even as different as the two exercises are. Pittsburgh gets very deep in the marrow of people who are from there. Folks I knew in high school who took great pride in moving to New York, or California, or wherever, bedeck their social media in black and gold on particular days in the autumn. It may sound tautological, but because I’m from Pittsburgh I had to write about Pittsburgh.

MAT: The research in this book must have been a massive undertaking. How did you do it?

ES: As with a lot of my writing—though not all— much of the research was done while I was writing the book. When writing an essay, I normally have a very narrow, circumscribed understanding of what I’m going to cover. A lot of that research is done in a traditional way, i.e., I gather the books I’m going to need, I read what I need, I assemble notes, I organize a flexible outline, and so on. For this book, each one of the chapters— which are short, discrete, and fragmentary— was like writing a type of hyper-intense flash non-fiction. I’d gather what I needed while writing an individual section. While writing those fragments I might come across a reference or footnote that pushed me to some book that I had no idea existed, and I’d mine what I could. This is true for any book, but An Alternative History of Pittsburgh is also a record of me learning about Pittsburgh itself.

MAT: How did you organize what you found?

ES: When I put together my proposal for Belt Publishing, I already had a detailed outline of all 40 chapters, with their synopses as fleshed out as possible. I knew roughly what I wanted for the structure of the book, a largely chronological collection of discrete narratives, character sketches, and thematic arguments. I hoped the relationships between the chapters would manifest an argument about the significance of Pittsburgh that was less historical or scholarly and more literary. There were certain places, people, and events I knew would be in the book—Fort Pitt, Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, the collapse of the steel industry. I also had more obscure, idiosyncratic things that I wanted to cover, like the utopian colony of the Harmonists, or the 1877 anarchist railroad strike. Ultimately, about 90 percent of what I proposed ended up in the book. Some chapters were merged, some were expanded, and a few were cut entirely.

MAT: Are you a Damon Young fan? I ran into him at the 2019 National Antiracist Book Festival and was too starstruck to speak, other than to blurt out that I was a huge fan.

ES: I am! I was an avid reader of his work with Very Smart Brothas, and his book of essays What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker is simultaneously trenchant and hilarious. As a voice specific to Pittsburgh, Young is crucial in questioning the “Pittsburgh is the most livable city in America” narratives that have existed for my entire life, because he asks— and answers— “For whom is Pittsburgh most livable for?” A lot of Pittsburghers—myself included—are very much in love with the city, but white folks can be blinded to the profound inequities that endure in the city. Damon Young isn’t the only young, gifted writer in Pittsburgh right now; there’s Brian Broome whose Punch Me Up to the Gods is an amazing memoir, and Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, which has rightly been hailed as a potential future classic. Philyaw recently announced she’s leaving Pittsburgh, and I’d encourage white Pittsburghers to read and think about the reasons why she gives for that decision.

ES: I am! I was an avid reader of his work with Very Smart Brothas, and his book of essays What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker is simultaneously trenchant and hilarious. As a voice specific to Pittsburgh, Young is crucial in questioning the “Pittsburgh is the most livable city in America” narratives that have existed for my entire life, because he asks— and answers— “For whom is Pittsburgh most livable for?” A lot of Pittsburghers—myself included—are very much in love with the city, but white folks can be blinded to the profound inequities that endure in the city. Damon Young isn’t the only young, gifted writer in Pittsburgh right now; there’s Brian Broome whose Punch Me Up to the Gods is an amazing memoir, and Deesha Philyaw’s The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, which has rightly been hailed as a potential future classic. Philyaw recently announced she’s leaving Pittsburgh, and I’d encourage white Pittsburghers to read and think about the reasons why she gives for that decision.

MAT: Thank you! I was gaga over Deesha Philyaw’s book and can’t recommend it highly enough. I look forward to reading Brian Broome’s. Can you talk to us about the Pittsburgh writers you discuss in your book?

ES: For a city of its size, Pittsburgh has an imposing literary history. John Edgar Wideman, Annie Dillard, Michael Chabon, Rachel Carson, Jack Gilbert, Gerald Stern, W.D. Snodgrass, and of course August Wilson. We’re overrepresented in fiction, poetry, and drama—Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle, chronicling life in the Black neighborhood of the Hill District, is arguably the greatest triumph of the last half-century of American theater. Dillard is possibly the most significant chronicler of nature over the past several decades, as is Carson obviously, in a more explicitly scientific way. Gilbert is among the greatest of poets to write in the 20th century, even if he isn’t a household name, as are Stern and Snodgrass. Chabon is a singularly brilliant writer who needs little introduction to the readers of The Millions, and Wideman’s Homewood is every bit as visceral and ghost-haunted as Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County.

ES: For a city of its size, Pittsburgh has an imposing literary history. John Edgar Wideman, Annie Dillard, Michael Chabon, Rachel Carson, Jack Gilbert, Gerald Stern, W.D. Snodgrass, and of course August Wilson. We’re overrepresented in fiction, poetry, and drama—Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle, chronicling life in the Black neighborhood of the Hill District, is arguably the greatest triumph of the last half-century of American theater. Dillard is possibly the most significant chronicler of nature over the past several decades, as is Carson obviously, in a more explicitly scientific way. Gilbert is among the greatest of poets to write in the 20th century, even if he isn’t a household name, as are Stern and Snodgrass. Chabon is a singularly brilliant writer who needs little introduction to the readers of The Millions, and Wideman’s Homewood is every bit as visceral and ghost-haunted as Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County.

MAT: How did you come to writing?

ES: I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was a kid. My first essays geared for a wider public were published about a decade ago. At that time, I was working on my PhD, and the bulk of writing that I’d done was scholarly. I slowly began to transition toward writing creative nonfiction, essays, reviews, and so on. I don’t write for acclaim, and Christ knows I don’t write for the money. I’m honored that anyone spends their limited time reading something I wrote. My essays pay for groceries, and that’s not nothing. But I saw something on Twitter the other day, where the OP asked if people would still write if they knew nobody would read their stuff, and my thought was Well of course I would. Writers write, that’s what we do—that’s what we need to do. Writing is how I organize my experience and make sense of the world; in some ways writing is itself synonymous with thinking for me.

MAT: Can you talk about the journey from academia to your current writing life?

ES: Bluntly, the journey out of academia isn’t necessarily a choice—it’s mandatory these days, especially for millennial scholars. There simply aren’t any tenure track jobs left, the profession itself is in free fall. While I know that being a fulltime faculty member must have its faults, my impression is that many working in that role have little clue how incredibly fortunate they were to do so before the profession was in decline. I’m incredibly envious. I’d love the romance of being a tenured professor somewhere, teaching students, and writing what I write right now, but with a salary and health insurance.

MAT: Can you talk about your journey to this publisher?

I first worked with Anne Trubek, founder and publisher at Belt, in 2015 when I wrote an essay for Belt Magazine entitled “The Sacred and the Profane in Pittsburgh,” about St. Anthony’s Chapel in Troy Hill on the Northside, which has more relics than anywhere but the Vatican. This was one of my earliest pieces that was popular—Neko Case tweeted a link! I’ve contributed something at least once or twice a year since. Belt Publishing is incredibly innovative and vital—Anne has created a small regional press with tremendous oomph. She’s addressing a conspicuous absence by highlighting writers and writing from the Rust Belt and the Midwest, regions that are often stereotyped, misunderstood, misinterpreted, or ignored by people on the coasts. The sheer variety of titles and authors that Anne has introduced to a wider audience is remarkable. My proposal was for an odd, unconventional book, halfway between a history and an impressionistic, fragmentary, creative nonfiction thing. Belt has been incredibly supportive, from proposal through publication. We’ve found a lot of readers, which speaks to the work that Belt does.

MAT: Tell us about your writing for The Millions? What are your writing interests? And where do you seek inspiration?

ES: The Millions is my literary home. I first started writing for them several years ago as a freelancer when Lydia Kiesling was editor, and I’ve been on staff since 2018. Both Lydia and now Adam Boretz have been incredible editors—supportive, insightful, and tolerant of my odder ideas. Since I’ve been a staff writer, I’ve been able to write all kinds of unconventional things. I’m so grateful and fortunate to find a wide audience for essays that might be viewed as too eccentric at other sites. I cover religion and history, sometimes writing in the same fragmentary style of my Pittsburgh book. Adam has also published a lot of my pieces centered in what I studied in graduate school, Renaissance literature, high theory, etc. I’ve done literary esoterica, things like a history of footnotes, an essay on marginalia, and a rumination on breaking the fourth wall. My fragment essays have been on things like a history of the color black, or accounts of people who’ve claimed to be messiahs, that sort of thing. There’s no site like The Millions. When C. Max Magee founded it decades ago, he helped create an institution. It’s a place that’s not just focused on publishing, but that’s also focused on reading. There’s a huge difference. It’s an honor to be able to contribute there.

MAT: Tell us about your reading life.

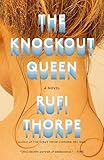

ES: Too much of my reading life is doom scrolling, but I’m the stay-at-home dad for a one-year-old. When you’re exhausted, sometimes Twitter is the easiest thing to read. I try to keep up on the smart literary things that are published, so checking Arts and Letters Daily is a morning ritual. I try to keep in mind advice by Linda Troost, a fantastic professor at W&J, who said we should try to make sure that when we’re at the (figurative) beach, we read a book from more than 200 years ago and a book from less than 20 years ago, so we can stay grounded in history and tradition and be open to the new. One incredible benefit to working at The Millions is that their much-loved year-end Year in Reading series provides an opportunity to stay grounded in contemporary literature. It keeps me centered in pleasure reading throughout the other 11 months of the year. I try keep up with new authors, or newish authors. Since January, I’ve read some fantastic novels, including Anna North’s Outlawed, Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League, Rufi Thorpe’s The Knockout Queen, Danielle Evans’s The Office of Historical Corrections, and the return of Andrea Lee in the incredible Red House Island.

ES: Too much of my reading life is doom scrolling, but I’m the stay-at-home dad for a one-year-old. When you’re exhausted, sometimes Twitter is the easiest thing to read. I try to keep up on the smart literary things that are published, so checking Arts and Letters Daily is a morning ritual. I try to keep in mind advice by Linda Troost, a fantastic professor at W&J, who said we should try to make sure that when we’re at the (figurative) beach, we read a book from more than 200 years ago and a book from less than 20 years ago, so we can stay grounded in history and tradition and be open to the new. One incredible benefit to working at The Millions is that their much-loved year-end Year in Reading series provides an opportunity to stay grounded in contemporary literature. It keeps me centered in pleasure reading throughout the other 11 months of the year. I try keep up with new authors, or newish authors. Since January, I’ve read some fantastic novels, including Anna North’s Outlawed, Emily Nemens’s The Cactus League, Rufi Thorpe’s The Knockout Queen, Danielle Evans’s The Office of Historical Corrections, and the return of Andrea Lee in the incredible Red House Island.

MAT: Did any books in particular influence your writing life?

ES: If I could write something as sublime as Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading, I’d be content. He’s a model for a particular type of eccentric, essayistic, exploration of esoterica, an author who can mine threads of obscure information to make an argument about what it means to be human. He writes with a light touch, humor, erudition, and most importantly pure curiosity.

ES: If I could write something as sublime as Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading, I’d be content. He’s a model for a particular type of eccentric, essayistic, exploration of esoterica, an author who can mine threads of obscure information to make an argument about what it means to be human. He writes with a light touch, humor, erudition, and most importantly pure curiosity.

MAT: What’s next for you?

ES: This has been an incredibly busy year. I’ve got two more books coming out in 2021, and a third scheduled for 2022. The first is an anthology of writing which I coedited with philosopher Costica Bradatan entitled The God Beat: What Journalism Says About Faith and Why it Matters, released by Broadleaf on June 8. We had the opportunity to work with a lot of fantastic writers like Ann Neumann, Brooke Wilensky-Lanford, Tara Isabella Burton, Marcus Rediker, Simon Critchley, Daniel Camacho, and so on. It was a tremendous honor. The second book is an art book that I’m really proud of with the absolutely amazing title of Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology, which looks beautiful and will be published by Abrams in October, in time for Halloween. Finally, sometime in 2022, Broadleaf will be releasing a collection of my essays entitled Binding the Ghost: Theology, Mystery, and the Transcendence of Literature. There are a few other nascent projects that I’m also working on.

ES: This has been an incredibly busy year. I’ve got two more books coming out in 2021, and a third scheduled for 2022. The first is an anthology of writing which I coedited with philosopher Costica Bradatan entitled The God Beat: What Journalism Says About Faith and Why it Matters, released by Broadleaf on June 8. We had the opportunity to work with a lot of fantastic writers like Ann Neumann, Brooke Wilensky-Lanford, Tara Isabella Burton, Marcus Rediker, Simon Critchley, Daniel Camacho, and so on. It was a tremendous honor. The second book is an art book that I’m really proud of with the absolutely amazing title of Pandemonium: A Visual History of Demonology, which looks beautiful and will be published by Abrams in October, in time for Halloween. Finally, sometime in 2022, Broadleaf will be releasing a collection of my essays entitled Binding the Ghost: Theology, Mystery, and the Transcendence of Literature. There are a few other nascent projects that I’m also working on.

MAT: I am in awe of your productivity! Anything else you want to talk about?

ES: Thanks. When it comes to an audience for An Alternative History of Pittsburgh, I want people to know that this isn’t just a book for Pittsburghers. One of the central arguments about the book is that Pittsburgh is a microcosm of America, and in its triumphs and failures, its exultation and wickedness, its good and its bad, there is something which the city can tell us about the nation of which it’s a part. Now, when we’re finally having a reckoning with what history really means, I hope my book can in some small way illuminate how we think about the past.