It’s an odd privilege to learn from someone you are in awe of. The senses seem to shut down, overwhelmed by brilliance. I know this from experience. Dana Spiotta was a teacher of mine. Her unsparing curiosity, her care for details, her devotion to the craft—in person, on the page—have been an endless source of inspiration. In Wayward (out now from Knopf), Spiotta continues her quiet run at the front of American fiction, with a novel that achieves ends sometimes thought exclusive: formal innovation and profound emotion.

Wayward might be most distinguished from Spiotta’s previous four novels by its subject. In the chaos of the recent past, at the time of Donald Trump’s election, through the particulars of a family in Syracuse, Spiotta confronts readers with the unseen terrain of menopause. Sam wakes at night in the Mid, which “always seemed to be precisely 3:00.” Sam struggles with comedically-rich impulses, such as “the urge to scream…at young women sometimes. She imagined herself shrieking ‘Menopause! Menopause! Menopause!’” Shopping, Sam reflects on clothes that were “flattering…to a grotesque midlife misshapenness—a blurriness, a squareness, really.” Sam becomes obsessed with the story of a middle-aged white woman who sneaks aboard planes without consequence. To age as a woman is to become invisible to the culture, Spiotta tells us, as she beautifully offers form to all the culture refuses to see.

Spiotta and I spoke over Zoom and exchanged emails about her new novel, the definition of structure, Ward Wellington Ward, lists. I was confident that, at the end of our conversation, I had just completed a master class on being alive.

The Millions: The struggle to be a better person—in an existential sense, in a moral sense—features prominently in all of your work. But it’s a struggle that has evolved from Lightning Field to Wayward, and, in its most recent form, it appears varied, new. Maybe we can start there, with talking a bit about this dilemma, often faced by your characters, to be someone better than they are.

The Millions: The struggle to be a better person—in an existential sense, in a moral sense—features prominently in all of your work. But it’s a struggle that has evolved from Lightning Field to Wayward, and, in its most recent form, it appears varied, new. Maybe we can start there, with talking a bit about this dilemma, often faced by your characters, to be someone better than they are.

Dana Spiotta: I remember when Lightning Field came out. Some people interpreted it as being ambivalent about morality. I didn’t understand that. I’m not concerned with this in a Christian way. I’m thinking of what Joy Williams says, about how a character can see with clarity in both directions. This is what interests me. It’s a version of a Joycean epiphany, to see yourself with clarity. It’s a struggle of being human. But then comes the challenge of what to do with what you learn. Of course, I don’t have the answers. Fiction is about consequence. About playing out the consequence. And part of playing out the consequence for me—because I’m a character-driven writer—is not so much about dramatic action, but, rather, that you can’t unsee what you see. My characters then have to choose to live with the compromise or try to change themselves.

In all of my novels the characters want to be better but are not necessarily able to. In Eat the Document, this takes the form of the characters wondering how to live in a capitalistic society and maintain their integrity. Nik, in Stone Arabia, struggles with something similar. That is, he finds a certain obligation to resist. And there are consequences of this for his family. Of course it’s your right to do whatever you want with your life, but it’s naive to ignore how you affect other people. Beyond that, I am increasingly interested in this question of responsibility toward others, in a broader sense, in the context of society. I think what feels most different about my work now, though, is that when trying to write about the broad cultural moment in Wayward, I go into a more local, more intimate field.

In all of my novels the characters want to be better but are not necessarily able to. In Eat the Document, this takes the form of the characters wondering how to live in a capitalistic society and maintain their integrity. Nik, in Stone Arabia, struggles with something similar. That is, he finds a certain obligation to resist. And there are consequences of this for his family. Of course it’s your right to do whatever you want with your life, but it’s naive to ignore how you affect other people. Beyond that, I am increasingly interested in this question of responsibility toward others, in a broader sense, in the context of society. I think what feels most different about my work now, though, is that when trying to write about the broad cultural moment in Wayward, I go into a more local, more intimate field.

TM: In Wayward, many of the consequences for Sam’s change are the result of her being a middle-aged woman. There’s this hilarious moment in the novel when Sam and her husband tell Ally, their daughter, that they’re splitting up, and Ally assumes that it’s her father leaving her mother. She can’t believe that it’s her mother who wants to leave.

DS: What interests me about Sam is that, as a middle-aged person, it’s harder for her to change. There is more self there. You’re more compromised. You’re part of the status quo. You have more to lose. The older you become it gets increasingly more difficult and more consequential to change. I thought it was important that it would be Sam’s idea to leave. Her rupture. Her will. I didn’t want it to be a miserable marriage or an unhappy life. I wanted her to leave behind a comfortable life. One of the ways the book works in the beginning is to sift through why she left.

TM: I’ve wanted to ask you how you define structure. In general, I tend to understand structure as patterning, but for Wayward, it seems we need a definition to include asymmetries, the deliberate resistance of pattern.

DS: I’m not too conscious of structure while I’m writing. I do think you can be overly schematic if you squeeze your story into an apparatus. Even if you look at works like Ulysses, a work that contains invented constraints—and it’s great to have constraints, you need constraints, in some sense that’s what structure is, the big invented constraint—but you constantly have to defeat over-patterning, defeat where it becomes predictable. I think about it on the level of a sentence. For the sentence, you can repeat a pattern, but you have to vary it, otherwise it becomes sing-songy, and horrible. You can have a little pattern based on sound and white space and diction and then have it evolve. Let’s say you have a three beat ending on your sentences. “It was this and this and this.” And then you switch it to: “This, and this.” And it ends with: “This.” You’re aware as you create a sentence of the patterns you’ve created in the previous sentences. You have all of these things you can do with the patterns you’ve established. And then you have all of these things to vary it with. So I think of structure in terms of the micro level of the sentence, the semi-micro level of the paragraph, the somewhat macro level of the chapter, and the macro level of the novel. But they all have the same structural concerns, and they’re all things you can play with as you go forward. Patterning connects the recursions. What I love about writing novels is that you can introduce something in the first 20 pages, and when it recurs 100 pages later, the reader will still remember it, the novel will be going sideways and forwards and back at the same time, and all the meaning is made. That creates a feeling of completeness.

DS: I’m not too conscious of structure while I’m writing. I do think you can be overly schematic if you squeeze your story into an apparatus. Even if you look at works like Ulysses, a work that contains invented constraints—and it’s great to have constraints, you need constraints, in some sense that’s what structure is, the big invented constraint—but you constantly have to defeat over-patterning, defeat where it becomes predictable. I think about it on the level of a sentence. For the sentence, you can repeat a pattern, but you have to vary it, otherwise it becomes sing-songy, and horrible. You can have a little pattern based on sound and white space and diction and then have it evolve. Let’s say you have a three beat ending on your sentences. “It was this and this and this.” And then you switch it to: “This, and this.” And it ends with: “This.” You’re aware as you create a sentence of the patterns you’ve created in the previous sentences. You have all of these things you can do with the patterns you’ve established. And then you have all of these things to vary it with. So I think of structure in terms of the micro level of the sentence, the semi-micro level of the paragraph, the somewhat macro level of the chapter, and the macro level of the novel. But they all have the same structural concerns, and they’re all things you can play with as you go forward. Patterning connects the recursions. What I love about writing novels is that you can introduce something in the first 20 pages, and when it recurs 100 pages later, the reader will still remember it, the novel will be going sideways and forwards and back at the same time, and all the meaning is made. That creates a feeling of completeness.

TM: Structure then becomes both the creation and destruction of patterning. Which I love. I want to make sure I ask about structures that influence you besides prose. I know paintings have been helpful for me.

DS: It’s interesting because when you’re confronted with a painting, you have to choose where to look first. Your eye eventually apprehends the whole thing. I think architecture does that as well. In Wayward, I reference Ward Wellington Ward, a real-life architect of the Arts and Crafts era. His work is not symmetrical but it is cohesive. He’ll have a fireplace with an inglenook and bookshelves nearby. He’ll have a patterning of windows that he’ll violate in some interesting way. It never feels messy. It feels purposeful, controlled. It’s that effect that makes me think of the comparison for writing. You want to have enough authority so that when you disrupt something structurally the reader is with you. If that makes sense.

TM: It does. Shifting a bit here, I wanted to ask about the setting for Wayward. Syracuse is this ultimate post-industrial and post-modern city. Your descriptions of Sam’s life here made me think of Red Desert. I know California is normally in your work, but why Syracuse, specifically, for this book?

DS: There has been more and more upstate New York in my work. All of the works had a California component though. And California is still really interesting to me. There’s an eccentricity to Los Angeles that I love, and upstate New York has that too. There is alternative culture everywhere. And it feels capacious. There’s a long history here of that “old weird” America. To me, the most appealing thing about America is how reformist and experimental it has been. It makes you want to take people aside and say, “What’s the point of all of this freedom if we’re just going to fall in line?” So people trying to do something countercultural—there’s a history of that in upstate New York with the women’s movement, abolition, and also all of these whackier things. It fascinates me. Like in Oneida, which I incorporate in Wayward.

I started researching the Oneida community and a lot of other 19th-century experiments in living for Eat the Document, but it didn’t make it in there. These were religious communities, and they were mostly concerned with counter cultural interpretations of how to be more Godly. In Oneida’s case, this involved a communal society without private property or private marriage. Part of what’s interesting about Oneida is that their community was so successful for so long. Which was partially because they were making things they could sell to the rest of the world. But as I was writing Wayward, I was thinking about how these alternative communities offered a kind of liberation for women. At Oneida, they could be in a religion that allowed them to have sex for pleasure, wear pants, and cut their hair. It’s not a coincidence that a lot of the culty religions in upstate New York had so many women active in them, either founding them or having major roles in them. When you think of Victorian culture and how limited women’s possibilities were because of constant childbirth, it’s also clear that menopause became a form of liberation. Once women were done with children, they could do other things. These alternative communities are fraught because they can’t really divorce themselves from the structures of the culture. You can’t say I’m going to make a non-patriarchal community because you’ve been raised by the patriarchy, so all of that shit comes with you. You could connect to a more modern instance of this, in Wayward, with Ally’s relationship with a much older man. It’s a recurrence of the questions the cult material raises, where sex is both a liberation but also has unintended consequences for her.

TM: I want to return to how Wayward fits in with your other novels. Often your work builds around a dramatic act of compassion. To me, this distinguishes your work. It’s never sentimental, but it is so concerned with compassion. Where does that come from?

DS: This was a big thing for me as a writer, a breakthrough. Learning to write emotional reality. Characters who are deranged with emotion. I think you can write unsentimentally about these things. You can’t be afraid of having consequential emotions in your book. You can undercut them without dismissing them or making fun of them. That’s what I really hope for in the work. The emotional connection between the readers and the characters. In this book, the humor is front loaded, and then it gets more serious.

TM: You said that was a breakthrough for you as a writer. What got you there?

DS: I grew up reading the writers of the ’70s, the postmodernists. In their work, you’re propelled forward but the expected revelation is taken away. It was discomforting and really powerful to me. But I found in my own writing, it became a kind of cheat. I remember in Eat the Document, I thought, Maybe I’ll never show what they did. And then my editor said, “I think we need to see it.” And I thought it would be corny, but once I wrote it I realized: yes, we needed to see it. Ultimately it’s about making meaning in an honest way. And for every writer that’s different. But for me, my honest relationship to the world is very emotional. I needed to be freer about that. Understand that derangement of emotion is a crucible for revelation. For me, then, the question becomes: can you be up to those moments as a writer? That’s difficult. It involves taking a risk.

TM: I want to ask about the role technology plays in Wayward. Similar to the struggle to change, this is something I see evolving through your work. There’s this passage in your debut, Lightning Field. The passage comes after a character introduces a camera into his romantic relationship with the book’s protagonist, Mina, who reflects on why “being filmed by Max was so deeply erotic…it wasn’t about vanity, damn it, it was about having the feeling that your life was being attended, about having your life signify something, some true thing.” This made me think of, in Wayward, Ally being asked by her boyfriend to send a picture of herself. I found Mina’s reflection to be so beautiful and sad. Of course, her situation is different from Ally’s. How do you see this technology complicating a relationship?

DS: In one case, Mina is being filmed. In another, Ally takes a selfie. But both are for men. In some ways, it’s compelling. To be closely paid attention to. But you’re also losing something in that. I think that comes up in Stone Arabia, too. It’s interesting that the Amish don’t want to be photographed. They were suspicious of the vanity of an image. In their view, a Christian vanity. Also, it’s interesting how easily the need to be seen in that way gets away from you. And, of course, in our society still, women are being taught that their value, their very existence, depends on being looked at in certain ways.

TM: I think it’s interesting how one-sided love through technology is. Technology in your work is both a way to transfer love but also to estrange.

DS: I’m very interested in incorporating what it’s like to be alive in the moment the book is set. One of the things I love about the form of the novel is that you only have prose to convey everything. That challenge—how to approach distinctly non-prose things—is exciting. I like writing about listening to music, about watching movies, about what it’s like to surf the Internet. So often my approach is to anchor the actual experience in the body and the consciousness of a character. But sometimes, other strategies work. You don’t want to be gimmicky, but this stuff is our lives. The technology has to be incorporated. We so seldomly think about the thinginess of what we use. What this object, this phone, is like in your hand. I was thinking about this a lot in Innocents and Others, the body relation you have to the technology. You can’t not engage it. It shapes who we are. Just like how the architecture of Sam’s house shapes who she is. Phones are machines for living.

DS: I’m very interested in incorporating what it’s like to be alive in the moment the book is set. One of the things I love about the form of the novel is that you only have prose to convey everything. That challenge—how to approach distinctly non-prose things—is exciting. I like writing about listening to music, about watching movies, about what it’s like to surf the Internet. So often my approach is to anchor the actual experience in the body and the consciousness of a character. But sometimes, other strategies work. You don’t want to be gimmicky, but this stuff is our lives. The technology has to be incorporated. We so seldomly think about the thinginess of what we use. What this object, this phone, is like in your hand. I was thinking about this a lot in Innocents and Others, the body relation you have to the technology. You can’t not engage it. It shapes who we are. Just like how the architecture of Sam’s house shapes who she is. Phones are machines for living.

TM: The language in the book has such energy. Syntactically you make brilliant use of lists. And you capture the smashup rhythms of Internet talk, the “faux po’/demi-dereliction.” But you also go deep into the particulars of a system here, the “chinoiserie,” the “inglenook.” There’s the gym-bro talk, the startup talk, the need to “optimize.” Then there’s the emotively lyrical, the “mildewed lemon wedge.” I would love to hear about your philosophy of language for Wayward. How did your relationship to language change (if at all) for this book? What I felt more in this book was the conflict between the different systems of language.

DS: A lot of my favorite writers do this. I do like subcultures that have an energetic jargon. When you invent new speech, at first it illuminates and then it obscures. It almost always tends toward euphemism. There’s often some sort of crime that gets committed, with the language covering it up. The more the language gets used the more problematic it becomes. And things get hammered into cliches that no one questions or thinks about. This is a big source of creativity for me. I also find it very funny, and pointing out what is funny about it is part of what energizes me.

I like lists. I like making lists. It’s an excess which I own. The list feels poetic. When you put things in a list, you put them in a syntactic relationship with each other that’s different from the usual way they’re viewed. You start to exist on the surface of the language in terms of the sound and look of it rather than how it’s used in the world. You’re dislocating that piece of language. You’re seeing new patterns, new relationships beyond the conventional ones.

TM: To end, I want to ask you about a scene in the novel where a character, MH, says: “Care? That the catastrophe that was human civilization is dribbling out? Why would I care about us?” To which Sam responds: “I don’t agree.” My question is: do you feel the novel is specifically equipped to take on the problem of building meaning? And, relatedly, do you feel the form of the novel has a responsibility to attempt to build some sort of meaning?

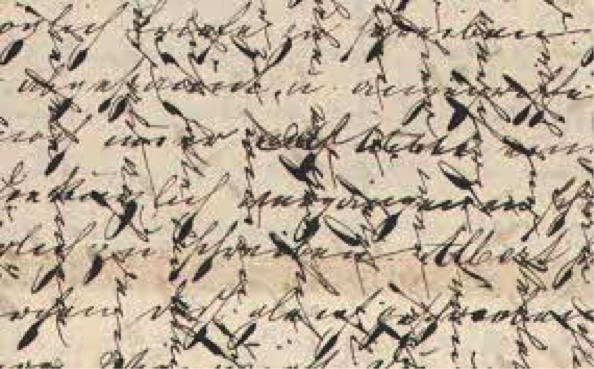

DS: I am drawn to humor as a means of expressing honesty, subversion, and joy. Also, I derive hope to from paying attention to the small details of human behavior in different contexts. I am particularly moved when I look at people and notice small acts of resistance. For an example, how some women in the past used to crosswrite letters to save money on postage. The result was formally beautiful but also very hard to read. Almost secret writing that was considered “feminine” and perverse. I admire the beauty, the eccentricity, and the recalcitrance of the act. It gives me hope. In a big sense, I am not bullish on America or humans in general most of the time, but I do think our job as writers is to stay curious about the species in all its paradoxes. Can we truthfully engage our own pessimism while still holding on to hope?