Here are five notable books of poetry publishing this month.

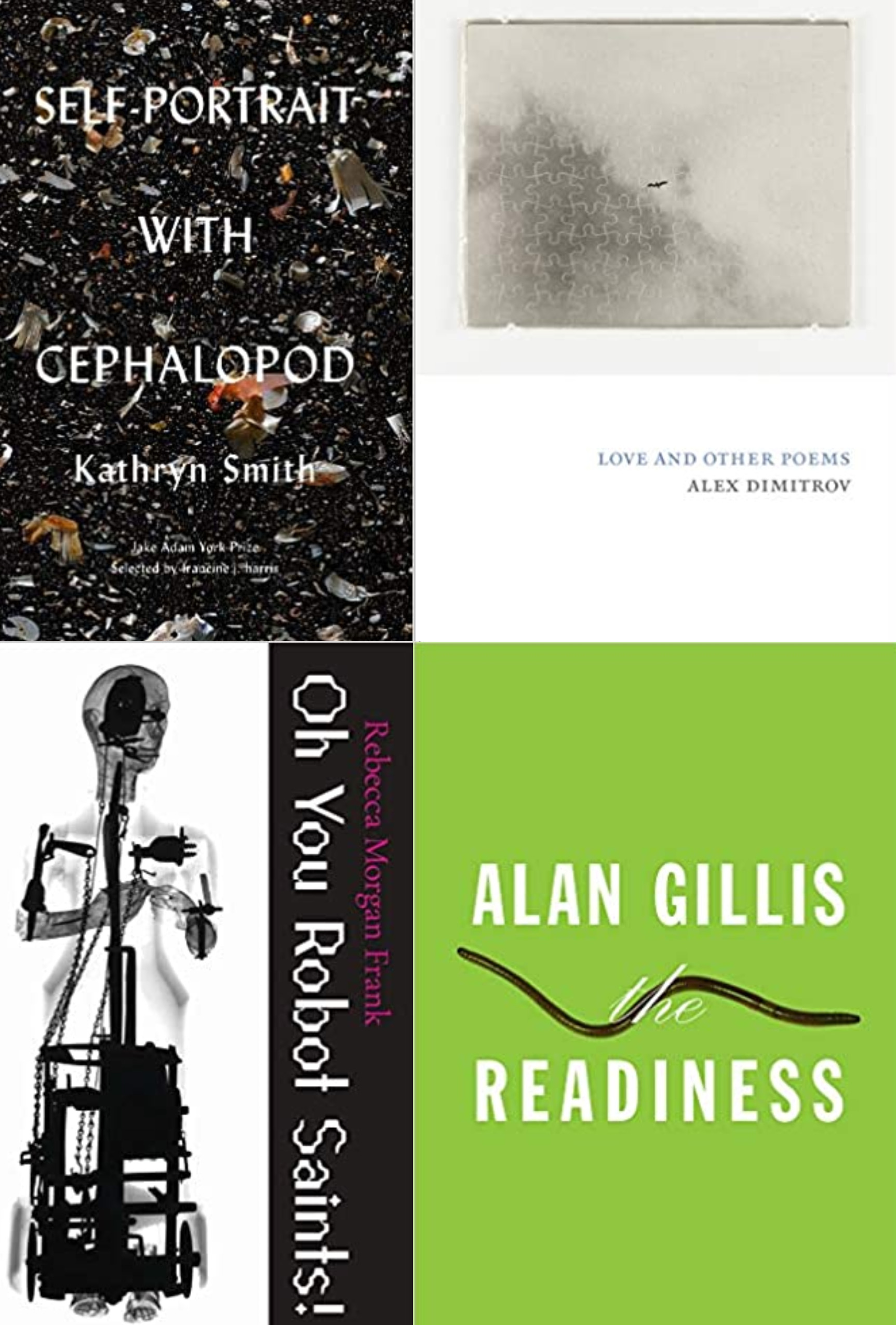

Love and Other Poems by Alex Dimitrov

Love and Other Poems by Alex Dimitrov

Dimitrov’s clever, casual, and inviting lines—“I don’t want to sound unreasonable / but I need to be in love immediately. / I can’t watch this sunset / on 14th Street by myself”—are especially welcome right now. But this is a complex collection; in “Waiting at Stonewall,” he ponders, 50 years later: “Those of us who resisted heroes / and sentiment. Those of us / who waited and found neither— / not the promised liberation / in marriage, or the salvation / of laws.” Sit down and appreciate “Love,” a long, anchoring litany-poem: “I love religious spaces though I’m sometimes lost there. / I love the sun for worshipping no one.” In “My Secret,” the narrator shares: “I’m suddenly / one of those people / who goes out / to dinner alone.” He knows: “Everyone I love / is disappointed in me.” This is a book about love, yes, but it is also one of the best recent books about New York City. If you love that city, if you hate that city, if you want to understand that city: read this book. His smirks and winks (“Or even worse / they’re going home to cook / and read this sad poem online”) are tender rather than tendentious; we are invited to experience this book. He calls out all of us, “Such righteous / saints! Repeating easy lines, / performing our great politics.” Dimitrov is good enough—his lines are smooth enough—that the guilty will gladly take the punishment.

Promoteo by C. Dale Young

Promoteo by C. Dale Young

“As a child,” Young writes in a poem halfway through this book, “I asked my mother to listen to me / while I practiced words like cobalt, each one more / and more odd for their sounds, their structures.” Drawn to syntax and sound, the narrator remembers the repetition of Mass—how he was “trying to master // the language, the very words, fearful they would master / me, instead.” Years later, Young, the poet (and radiation oncologist) has mastered language in this finely wrought new volume. Continuing a tradition from previous books like The Second Person, Young’s narrators have inherited languages of religion and desire, and they intertwine in their ecstasy. “You punish or are punished,” he writes. “It really is that simple. // Dominus, Holy Father. I have hidden myself / in the cane field. I may have sinned.” “Portrait in Ochre and Seven Whispers” is a searing poem of suffering and abuse, beginning with: “To make and remake one’s self is / the artist’s job, I believed. And so, in poems, / I gave myself wings.” The narrator later laments: “You were supposed to save us. You were / supposed to help save our souls. Isn’t that part / of the vow you made to God when choosing / the life you did?” He ends the stanza: “You must have forgotten that. / You didn’t kill my soul. But you didn’t save it either.” An excellent book.

Self-Portrait with Cephalopod by Kathryn Smith

Self-Portrait with Cephalopod by Kathryn Smith

Playful and smart: Smith shows those traits can synthesize into memorable poems (with great titles). In “Most of Us Aren’t Beautiful, Though Some Learn How,” she admits: “I’m back // where I started: stuck in a parable / I cannot, botanically, and do not, // theologically, believe.” In the first poem, Smith writes: “The beauty of birds isn’t flight. It’s how they let / their young cram pointy beaks down their throats.” In “Dear Sirs,” she wonders—if the “traditional forms of revelation” included “interpretable dream, flashes of light,” then what “are some of the modern forms?” It’s a good question, and Smith is comfortable not answering it, resigned to a truth: “I fear that fire // will burn the insides of my eyes, / flames licking the wounds and disappearing / names of the dead.” Smith’s poems often ponder an entropic world through a theology of absence: “It is said in God / there is no darkness. / It is also said / I am made / in God’s image.” In this way, “I am fearfully and wonderfully / made, made wonderfully / fearful.” She concludes: “Surely goodness / will dog me all the days / of my life.”

Oh You Robot Saints! by Rebecca Morgan Frank

Oh You Robot Saints! by Rebecca Morgan Frank

God in the machine, God is the machine: Frank’s new book is a menagerie of automation, automatons, sentient verse, errant prophecies. She considers the tradition of mechanical Eves: “fetching your tea, serving / you wine,” they “didn’t have a mind” and “were built from the ribs / of men’s brains.” “Oh, man has made her!” Frank intones (long live exclamation points in poems!), “and she is uncanny (and / infertile!).” Man has long made women “in his own image / for beauty and service, oh, man has / made her, a more pliable Eve / with no desire of her own.” I think of how Thomas Pynchon lifted the Luddites from their 19th century economic vengeance to their contemporary technophobia; Frank similarly mines past art, story, and parable for astoundingly contemporary truths. She follows the metaphor of body-as-machine to its logical end: we are all gears, oiled, “no different than that of medieval / mechanical monkeys lining the bridge // in the park at Hesdin.” Eye-opening, jaunty: this is a whirl of a book.

The Readiness by Alan Gillis

The Readiness by Alan Gillis

What routes these lines take. Gillis begins one poem with an earthworm who “squinches / through soil to ooze in dew, / only to be pincered / in the beak of a crow, // lifted above the garden, the gable wall, into a sky / of porridge / with faint pools of blue.” I’m a believer in poetic surprise (when Frost created that image of ice on a hot stove, he knew that sometimes the ice melted into itself and steamed into the air: no surprise for the poet, no surprise for the reader, and so on). Gillis delivers, finding the lolling and lyric in the everyday: “get set for the whigmaleeries of the ticking clock, / spilt milk, the mystery / of missing socks, the transport peeve, the hundred-tonne / weight of to-dos.” Maybe poetry isn’t utilitarian in a grand, salvific sense, but it is a cure for language, and it might be a method to sing boredom into beauty. Gillis wants us to be ready: revelations, small and strange, “could happen at sunset / on a sloping lawn. / In a yawning estate / it could happen at dawn.” “Everything changes,” Gillis writes in a later poem. “In this there is no change.” Gillis’s willingness to bounce between jest and earnestness is a good reminder of how comic-poets can stun us with their well-placed truths: “And you know this, / the oncoming day, is nothing / but the night’s brief parenthesis.”