1.

In a purple-walled gallery of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, you can visit the shrine constructed by Air Force veteran and janitor James Hampton for Jesus Christ’s return. Entitled “Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation’s Millennium General Assembly,” the altar and its paraphernalia were constructed to serve as temple objects for the messiah, who according to Hampton, based on visions he had of Moses in 1931, the Virgin Mary in 1946, and Adam in 1949, shall arrive in Washington D.C. His father had been a part-time gospel singer and Baptist preacher, but Hampton drew not just from Christianity, but brought Afrocentric folk traditions of his native South Carolina to bear in his composition. Decorated with passages from Daniel and Revelation, Hampton’s thinking (done in secret over 14 years in his Northwest Washington garage) is explicated in his 100-page manifesto St. James: The Book of the 7 Dispensations (dozens of pages are still in an uncracked code). Claiming that he had received a revised version of the Decalogue, Hampton’s notebook declared himself to be “Director, Special Projects for the State of Eternity.” His work is a fugue of word salad, a concerto of pressured speech. A combined staging ground for the incipient millennium—Hampton’s shrine is a triumph.

As if the bejeweled shield of the Urim and the Thummim were constructed not by Levites in ancient Jerusalem, but by a janitor in Mt. Vernon. Exodus and Leviticus give specifications for those liturgical objects of the Jewish Temple—the other-worldly cherubim gilded, their wings touching the hem of infinity huddled over the Ark of the Covenant; the woven brocade curtain with its many-eyed Seraphim rendered in fabric of red and gold; the massive candelabra of the ritual menorah. The materials with which the Jews built their Temple were cedar and sand stone, gold and precious jewels. When God commanded Hampton to build his new shrine, the materials were light-bulbs and aluminum foil, door frames and chair legs, pop cans and cardboard boxes, all held together with glue and tape. The overall effect is, if lacking in gold and cedar, transcendent nonetheless. Hampton’s construction looks almost Mesoamerican, aluminum foil delicately hammered onto carefully measured cardboard altars, names of prophets and patriarchs from Ezekiel to Abraham rendered.

Everyday Hampton would return from his job at the General Services Administration, where he would mop floors and disinfect counters, and for untold hours he’d assiduously sketch out designs based on his dreams, carefully applying foil to wood and cardboard, constructing crowns from trash he’d collected on U Street. What faith would compel this, what belief to see it finished? Nobody knew he was doing it. Hampton would die of stomach cancer in 1964, never married, and with few friends or family. The shrine would be discovered by a landlord angry about late rent. Soon it would come to the attention of reporters, and then the art mavens who thrilled to the discovery of “outsider” art—that is work accomplished by the uneducated, the mentally disturbed, the impoverished, the religiously zealous. “Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation’s Millennium General Assembly” would be purchased and donated to the Smithsonian (in part through the intercession of artist Robert Rauschenberg) where it would be canonized as the Pieta of American visionary art, outsider art’s Victory of Samothrace.

Hampton wasn’t an artist though—he was a prophet. He was Elijah and Elisha awaiting Christ in the desert. Daniel Wojcik writes in Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma that “apocalyptic visions often have been expressions of popular religiosity, as a form of vernacular religion, existing at a grassroots level apart from the sanction of religious authority.” In that regard Hampton was like so many prophets before him, just working in toilet paper and beer can rather than papyrus—he was Mt. Vernon’s Patmos. Asking if Hampton was mentally ill is the wrong question; it’s irrelevant if he was schizophrenic, bipolar. Etiology only goes so far in deciphering the divine language, and who are we so sure of ourselves to say that the voice in a janitor’s head wasn’t that of the Lord? Greg Bottoms writes in Spiritual American Trash: Portraits from the Margins of Art and Faith that Hampton “knew he was chosen, knew he was a saint, knew he had been granted life, this terrible, beautiful life, to serve God.” Who among us can say that he was wrong? In his workshop, Hampton wrote on a piece of paper “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” There are beautiful and terrifying things hidden in garages all across America; there are messiahs innumerable. Hampton’s shrine is strange, but it is oh so resplendent.

Hampton wasn’t an artist though—he was a prophet. He was Elijah and Elisha awaiting Christ in the desert. Daniel Wojcik writes in Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma that “apocalyptic visions often have been expressions of popular religiosity, as a form of vernacular religion, existing at a grassroots level apart from the sanction of religious authority.” In that regard Hampton was like so many prophets before him, just working in toilet paper and beer can rather than papyrus—he was Mt. Vernon’s Patmos. Asking if Hampton was mentally ill is the wrong question; it’s irrelevant if he was schizophrenic, bipolar. Etiology only goes so far in deciphering the divine language, and who are we so sure of ourselves to say that the voice in a janitor’s head wasn’t that of the Lord? Greg Bottoms writes in Spiritual American Trash: Portraits from the Margins of Art and Faith that Hampton “knew he was chosen, knew he was a saint, knew he had been granted life, this terrible, beautiful life, to serve God.” Who among us can say that he was wrong? In his workshop, Hampton wrote on a piece of paper “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” There are beautiful and terrifying things hidden in garages all across America; there are messiahs innumerable. Hampton’s shrine is strange, but it is oh so resplendent.

2.

By the time Brother John Nayler genuflected before George Fox, the founder of the Quaker Society of Friends, his tongue had already been bored with a hot iron poker and the letter “B” (for “Blasphemer”) had been branded onto his forehead by civil authorities. The two had not gotten along in the past, arguing over the theological direction of the Quakers, but by 1659 Nayler was significantly broken by their mutual enemies that he was forced to drag himself to Fox’s parlor and to beg forgiveness. Three years had changed the preacher’s circumstances, for it was in imitation of the original Palm Sunday that in 1656 Nayler had triumphantly entered into the sleepy sea-side town of Bristol upon the back of a donkey, the religious significance of the performance inescapable to anyone. A supporter noted in a diary that Nayler’s “name is no more to be called James but Jesus,” while in private writings Fox noted that “James ran out into imaginations… and they raised up a great darkness in the nation.”

At the start of 1656, Nayler was imprisoned, and when Fox visited him in his cell, the latter demanded that the former kiss his foot (belying the Quaker reputation for modesty). “It is my foot,” Fox declared, but Nayler refused. The confidence of a man who reenacted Christ’s entrance into Jerusalem. Guided by the Inner Light that Quakers saw as supplanting even the gospels, Nayler thought of his mission in messianic terms, and organized his vehicle to reflect that. Among the “Valiant Sixty,” itinerant preachers who were too radical even for the Quakers, Nayler was the most revolutionary, condemning slavery, enclosure, and private property. The tragedy of Nayler is that he happened to not actually be the messiah. Before his death, following an assault by a highwayman in 1660, Nayler would write that his “hope is to outlive all wrath and contention, and to wear out all exaltation and cruelty, or whatever is of a nature contrary to itself.” He was 42, beating Christ by almost a decade.

“Why was so much fuss made?” asks Christopher Hill in his classic The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. “There had been earlier Messiahs—William Franklin, Arise Evans who told the Deputy Recorder of London that he was the Lord his God…Gadbury was the Spouse of Christ, Joan Robins and Mary Adams believed they were about to give birth to Jesus Christ.” Hill’s answer to the question of Nayler’s singularity is charitable, writing that none of the others actually seemed dangerous, since they were merely “holy imbeciles.” The 17th-century, especially around the time of the English civil wars, was an age of blessed insanity, messiahs proliferating like dandelions after a spring shower. There was John Reeve, Laurence Clarkson, and Lodowicke Muggleton, who took turns arguing over which were the two witnesses mentioned in Revelation, and that God had absconded from heaven and the job was now open. Abiezer Cope, prophet of a denomination known as the Ranters, demonstrated that designation in his preaching and writing. One prophet, Thoreau John Tany (who designated himself “King of the Jews”), simply declared “What I have written, I have written,” including the radical message that hell was liberated and damnation abolished. Regarding the here and now, Tany had some similar radical prescriptions, including to “feed the hungry, clothe the naked, oppress none, set free them bounden.”

“Why was so much fuss made?” asks Christopher Hill in his classic The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution. “There had been earlier Messiahs—William Franklin, Arise Evans who told the Deputy Recorder of London that he was the Lord his God…Gadbury was the Spouse of Christ, Joan Robins and Mary Adams believed they were about to give birth to Jesus Christ.” Hill’s answer to the question of Nayler’s singularity is charitable, writing that none of the others actually seemed dangerous, since they were merely “holy imbeciles.” The 17th-century, especially around the time of the English civil wars, was an age of blessed insanity, messiahs proliferating like dandelions after a spring shower. There was John Reeve, Laurence Clarkson, and Lodowicke Muggleton, who took turns arguing over which were the two witnesses mentioned in Revelation, and that God had absconded from heaven and the job was now open. Abiezer Cope, prophet of a denomination known as the Ranters, demonstrated that designation in his preaching and writing. One prophet, Thoreau John Tany (who designated himself “King of the Jews”), simply declared “What I have written, I have written,” including the radical message that hell was liberated and damnation abolished. Regarding the here and now, Tany had some similar radical prescriptions, including to “feed the hungry, clothe the naked, oppress none, set free them bounden.”

There have been messianic claimants from first century Judea to contemporary Utah. When St. Peter was still alive there was the Samaritan magician Simon Magus, who used Christianity as magic and could fly, only to be knocked from the sky during a prayer-battle with the apostle. In the third century the Persian prophet Mani founded a religion that fused Christ with the Buddha, that had adherents from Gibraltar to Jinjiang, and a reign that lasted more than a millennium (with its teachings smuggled into Christianity by former adherent St. Augustine). A little before Mani, and a Phrygian prophet named Montanus declared himself an incarnation of the Holy Spirit, along with his consorts Priscilla and Maximillia. Prone to fits of convulsing revelation, Montanus declared “Lo, the man is as a lyre, and I fly over him as a pick.” Most Church Fathers denounced Montanism as rank heresy, but not Tertullian, who despite being the primogeniture of Latin theology, was never renamed “St. Tertullian” because of those enthusiasms. During the Middle Ages, at a time when stereotype might have it that orthodoxy reigned triumphant, and mendicants and messiahs, some whose names aren’t preserved to history and some who amassed thousands of followers, proliferated across Europe. Norman Cohn remarks in The Pursuit of the Millennium that for one eighth-century Gaulish messiah named Aldebert, followers “were convinced that he knew all their sins…and they treasured as miracle-working talismans the nail pairings and hair clippings he distributed among them.” Pretty impressive, but none of us get off work for Aldebert’s birthday.

There have been messianic claimants from first century Judea to contemporary Utah. When St. Peter was still alive there was the Samaritan magician Simon Magus, who used Christianity as magic and could fly, only to be knocked from the sky during a prayer-battle with the apostle. In the third century the Persian prophet Mani founded a religion that fused Christ with the Buddha, that had adherents from Gibraltar to Jinjiang, and a reign that lasted more than a millennium (with its teachings smuggled into Christianity by former adherent St. Augustine). A little before Mani, and a Phrygian prophet named Montanus declared himself an incarnation of the Holy Spirit, along with his consorts Priscilla and Maximillia. Prone to fits of convulsing revelation, Montanus declared “Lo, the man is as a lyre, and I fly over him as a pick.” Most Church Fathers denounced Montanism as rank heresy, but not Tertullian, who despite being the primogeniture of Latin theology, was never renamed “St. Tertullian” because of those enthusiasms. During the Middle Ages, at a time when stereotype might have it that orthodoxy reigned triumphant, and mendicants and messiahs, some whose names aren’t preserved to history and some who amassed thousands of followers, proliferated across Europe. Norman Cohn remarks in The Pursuit of the Millennium that for one eighth-century Gaulish messiah named Aldebert, followers “were convinced that he knew all their sins…and they treasured as miracle-working talismans the nail pairings and hair clippings he distributed among them.” Pretty impressive, but none of us get off work for Aldebert’s birthday.

More recently, other messiahs include the 18th-century prophetess and mother of the Shakers Anne Lee, the 20th-century founder of the Korean Unification Church Sun Myung Moon (known for his elaborate mass weddings and owning the conservative Washington Times), and the French test car driver Claude Vorilhon who renamed himself Raël and announced that he was the son of an extraterrestrial named Yahweh (more David Bowe’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars then Paul’s epistles). There are as many messiahs as there are people; there are malicious messiahs and benevolent ones, deluded head-cases and tricky confidence men, visionaries of transcendent bliss and sputtering weirdos. What unites all of them is an observation made by Reeve that God speaks to them as “to the hearing of the ear as a man speaks to a friend.”

More recently, other messiahs include the 18th-century prophetess and mother of the Shakers Anne Lee, the 20th-century founder of the Korean Unification Church Sun Myung Moon (known for his elaborate mass weddings and owning the conservative Washington Times), and the French test car driver Claude Vorilhon who renamed himself Raël and announced that he was the son of an extraterrestrial named Yahweh (more David Bowe’s The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars then Paul’s epistles). There are as many messiahs as there are people; there are malicious messiahs and benevolent ones, deluded head-cases and tricky confidence men, visionaries of transcendent bliss and sputtering weirdos. What unites all of them is an observation made by Reeve that God speaks to them as “to the hearing of the ear as a man speaks to a friend.”

3. Hard to identify Elvis Presley’s apotheosis. Could have been the ’68 Comeback Special, decked in black leather warbling “Suspicious Minds” in that snarl-mumble. Elvis’s years in the wilderness precipitated by his manager Col. Tom Parker’s disastrous gambit to have the musician join the army, only to see all of the industry move on from his rockabilly style, now resurrected on a Burbank sound stage. Or maybe it was earlier, on The Milton Berle Show in 1956, performing Big Mama Thorton’s hit “Hound Dog” to a droopy dog, while gyrating on the Hollywood stage, leading a critic for the New York Daily News to opine that Elvis “gave an exhibition that was suggestive and vulgar, tinged with the kind of animalism that should be confined to dives and bordellos.” A fair candidate for that moment of earthly transcendence could be traced back to 1953, when in Sun Records’ dusty Memphis studio Elvis would cover Junior Parker’s “Mystery Train,” crooning out in a voice both shaky and confident over his guitar’s nervous warble “Train I ride, sixteen coaches long/Train I ride, sixteen coaches long/Well that long black train, got my baby and gone.” But in my estimation, and at the risk of sacrilege, Elvis’s ascension happened on Aug. 16, 1977 when he died on the toilet in the private bathroom of his tacky and opulent Graceland estate.

Hard to identify Elvis Presley’s apotheosis. Could have been the ’68 Comeback Special, decked in black leather warbling “Suspicious Minds” in that snarl-mumble. Elvis’s years in the wilderness precipitated by his manager Col. Tom Parker’s disastrous gambit to have the musician join the army, only to see all of the industry move on from his rockabilly style, now resurrected on a Burbank sound stage. Or maybe it was earlier, on The Milton Berle Show in 1956, performing Big Mama Thorton’s hit “Hound Dog” to a droopy dog, while gyrating on the Hollywood stage, leading a critic for the New York Daily News to opine that Elvis “gave an exhibition that was suggestive and vulgar, tinged with the kind of animalism that should be confined to dives and bordellos.” A fair candidate for that moment of earthly transcendence could be traced back to 1953, when in Sun Records’ dusty Memphis studio Elvis would cover Junior Parker’s “Mystery Train,” crooning out in a voice both shaky and confident over his guitar’s nervous warble “Train I ride, sixteen coaches long/Train I ride, sixteen coaches long/Well that long black train, got my baby and gone.” But in my estimation, and at the risk of sacrilege, Elvis’s ascension happened on Aug. 16, 1977 when he died on the toilet in the private bathroom of his tacky and opulent Graceland estate.

The story of Elvis’s death has the feeling of both apocrypha and accuracy, and like any narrative that comes from that borderland country of the mythic, it contains more truth than the simple facts can impart. His expiration is a uniquely American death, but not an American tragedy, for Elvis was able to get just as much out of this country as the country ever got out of him, and that’s ultimately our true national dream. He grabbed the nation by its throat and its crotch, and with pure libidinal fury was able to incarnate himself as the country. All of the accoutrement—the rhinestone jumpsuits, the karate and the Hawaiian schtick, the deep-fried-peanut-butter-banana-and-bacon-sandwiches, the sheer pill-addicted corpulence—are what make him our messiah. Even the knowing, obvious, and totally mundane observation that he didn’t write his own music misses the point. He wasn’t a creator—he was a conduit. Greil Marcus writes in Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll of the “borders of Elvis Presley’s delight, of his fine young hold on freedom…[in his] touch of fear, of that old weirdness.” That’s the Elvis that saves, the Elvis of “That’s All Right (Mama)” and “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” those strange hillbilly tracks, that weird chimerical sound—complete theophany then and now.

The story of Elvis’s death has the feeling of both apocrypha and accuracy, and like any narrative that comes from that borderland country of the mythic, it contains more truth than the simple facts can impart. His expiration is a uniquely American death, but not an American tragedy, for Elvis was able to get just as much out of this country as the country ever got out of him, and that’s ultimately our true national dream. He grabbed the nation by its throat and its crotch, and with pure libidinal fury was able to incarnate himself as the country. All of the accoutrement—the rhinestone jumpsuits, the karate and the Hawaiian schtick, the deep-fried-peanut-butter-banana-and-bacon-sandwiches, the sheer pill-addicted corpulence—are what make him our messiah. Even the knowing, obvious, and totally mundane observation that he didn’t write his own music misses the point. He wasn’t a creator—he was a conduit. Greil Marcus writes in Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll of the “borders of Elvis Presley’s delight, of his fine young hold on freedom…[in his] touch of fear, of that old weirdness.” That’s the Elvis that saves, the Elvis of “That’s All Right (Mama)” and “Shake, Rattle, and Roll,” those strange hillbilly tracks, that weird chimerical sound—complete theophany then and now.

There’s a punchline quality to that contention about white-trash worshipers at the Church of Elvis, all of those sightings in the Weekly World News, the Las Vegas impersonators of various degrees of girth, the appearance of the singer in the burnt pattern of a tortilla. This is supposedly a faith that takes its pilgrimage to Graceland as if it were zebra-print Golgotha, that visits Tupelo as if it were Nazareth. John Strausbaugh takes an ethnographer’s calipers to Elvism, arguing in E: Reflections on the Birth of the Elvis Faith that Presley has left in his wake a bona fide religion, with its own liturgy, rituals, sacraments, and scripture. He writes that it is a “The fact that outsiders can’t take it seriously may turn out to be its strength and its shield. Maybe by the time Elvism is taken seriously it will have quietly grown too large and well established to be crushed.” There are things less worthy of your worship than Elvis Presley. If we were to think of an incarnation of the United States, of a uniquely American messiah, few candidates would be more all consumingly like the collective nation. In his appetites, his neediness, his yearning, his arrogance, his woundedness, his innocence, his simplicity, his cunning, his coldness, and his warmth, he was the first among Americans. Elvis is somehow both rural and urban, northern and southern, country and rock, male and female, white and black. Our contradictions are reconciled in him. “Elvis lives in us,” Strausbaugh writes, “There is only one King and we know who he is.” We are Elvis and He was us.

There’s a punchline quality to that contention about white-trash worshipers at the Church of Elvis, all of those sightings in the Weekly World News, the Las Vegas impersonators of various degrees of girth, the appearance of the singer in the burnt pattern of a tortilla. This is supposedly a faith that takes its pilgrimage to Graceland as if it were zebra-print Golgotha, that visits Tupelo as if it were Nazareth. John Strausbaugh takes an ethnographer’s calipers to Elvism, arguing in E: Reflections on the Birth of the Elvis Faith that Presley has left in his wake a bona fide religion, with its own liturgy, rituals, sacraments, and scripture. He writes that it is a “The fact that outsiders can’t take it seriously may turn out to be its strength and its shield. Maybe by the time Elvism is taken seriously it will have quietly grown too large and well established to be crushed.” There are things less worthy of your worship than Elvis Presley. If we were to think of an incarnation of the United States, of a uniquely American messiah, few candidates would be more all consumingly like the collective nation. In his appetites, his neediness, his yearning, his arrogance, his woundedness, his innocence, his simplicity, his cunning, his coldness, and his warmth, he was the first among Americans. Elvis is somehow both rural and urban, northern and southern, country and rock, male and female, white and black. Our contradictions are reconciled in him. “Elvis lives in us,” Strausbaugh writes, “There is only one King and we know who he is.” We are Elvis and He was us.

4.  A hideous slaughter followed those settlers as they drove deep into the continent. On that western desert, where the lurid sun’s bloodletting upon the burnt horizon signaled the end of each scalding day, a medicine man and prophet of the Paiute people had a vision. In a trance, Wodziwob received an oracular missive, that “within a few moons there was to be a great upheaval or earthquake… he whites would be swallowed up, while the Indians would be saved.” Wodziwob would be the John the Baptist to a new movement, for though he would die in 1872, the ritual practice that he taught—the Ghost Dance—would become a rebellion against the genocidal policy of the U.S. Government. For Wodziwob, the Ghost Dance was an affirmation, but it has also been remembered as a doomed moment. “To invoke the Ghost Dance has been to call up an image of indigenous spirituality by turns militant, desperate, and futile,” writes Louis S. Warren in God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America, “a beautiful dream that died.” But a dream that was enduring.

A hideous slaughter followed those settlers as they drove deep into the continent. On that western desert, where the lurid sun’s bloodletting upon the burnt horizon signaled the end of each scalding day, a medicine man and prophet of the Paiute people had a vision. In a trance, Wodziwob received an oracular missive, that “within a few moons there was to be a great upheaval or earthquake… he whites would be swallowed up, while the Indians would be saved.” Wodziwob would be the John the Baptist to a new movement, for though he would die in 1872, the ritual practice that he taught—the Ghost Dance—would become a rebellion against the genocidal policy of the U.S. Government. For Wodziwob, the Ghost Dance was an affirmation, but it has also been remembered as a doomed moment. “To invoke the Ghost Dance has been to call up an image of indigenous spirituality by turns militant, desperate, and futile,” writes Louis S. Warren in God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America, “a beautiful dream that died.” But a dream that was enduring.

While in a coma precipitated by scarlet fever, during a solar eclipse, on New Year’s Day of 1889, a Northern Paiute Native American who worked on a Carson City, Nevada, ranch and was known as Jack Wilson by his coworkers and as Wovoka to his own people, fell into a mystical vision not unlike Wodziwob’s. Wovoka met many of his dead family members, he saw the prairie that exists beyond that which we can see, and he held counsel with Jesus Christ. Wovoka was taught the Ghost Dance, and learned what Sioux Chief Lame Deer would preach, that “the people…could dance a new world into being.” When Wovoka returned he could control the weather, he was able to compel hail from the sky, he could form ice with his hands on the most sweltering of days. The Ghost Dance would spread throughout the western United States, embraced by the Paiute, the Dakota, and the Lakota. Lame Deer said that the Ghost Dance would roll up the earth “like a carpet with all the white man’s ugly things—the stinking new animals, sheep and pigs, the fences, the telegraph poles, the mines and factories. Underneath would be the wonderful old-new world.”

A messiah is simultaneously the most conservative and most radical, preaching a return to a perfected world that never existed but also the overturning of everything of this world, of the jaundiced status quo. The Ghost Dance married the innate strangeness of Christianity to the familiarity of native religion, and like both it provided a blueprint for how to overthrow the fallen things. Like all true religion, the Ghost Dance was incredibly dangerous. That was certainly the view of the U.S. Army and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which saw an apocalyptic faith as a danger to white settler-colonials and their indomitable, zombie-like push to the Pacific. Manifest Destiny couldn’t abide by the hopefulness of a revival as simultaneously joyful and terrifying as the Ghost Dance, and so an inevitable confrontation awaited.

The Miniconjou Lakota people, forced into the Pine Ridge Reservation by 1890, were seen as particularly rebellious, in part because their leader Spotted Elk was an adherent. As a pretext concerning Lakota resistance to disarmament, the army opened fire on gathered Miniconjou, and more than 150 people (mostly women and children) would be slaughtered during the Wounded Knee Massacre. As surely as the Romans threw Christians to the lions and Cossacks rampaged through the Jewish shtetls of eastern Europe, so too were the initiates of the Ghost Dance persecuted, murdered, and martyred by the U.S. Government. Warren writes that the massacre “has come to stand in for the entire history of the religion, as if the hopes of all of its devoted followers began and ended in that fatal ravine.” Wounded Knee was the Calvary of the Ghost Dance faith, but if Calvary has any meaning it’s that crucified messiahs have a tendency not to remain dead. In 1973 a contingent of Oglala Lakota and members of the American Indian Movement occupied Wounded Knee, and the activist Mary Brave Beard defiantly performed the Ghost Dance, again.

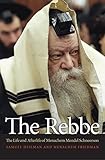

5.  Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson arrived in the United States via Paris, via Berlin, and ultimately via Kiev. He immigrated to New York on the eve of America’s entry into the Second World War, and in that interim six million Jews were immolated in Hitler’s ovens—well over half of all the Jews in the world. Becoming Lubavitch Chief Rebbe in 1950, Schneerson was a refugee from a broken Europe that had devoured itself. Schneerson’s denomination of Hasidism had emerged after the vicious Cossack-led pogroms that punctuated life in 17th-century eastern Europe, when many Jews turned towards the sect’s founder, the Baal Shem Tov. His proper name was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, and his title (often shortened to “Besht”) meant “Master of the Good Name,” for the Baal Shem Tov incorporated Kabbalah into a pietistic movement that enshrined emotion over reason, feeling over logic, experience over philosophy. David Bial writes in Hasidism: A New History that the Besht espoused “a new method of ecstatic joy and a new social structure,” a fervency that lit a candle against persecution’s darkness.

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson arrived in the United States via Paris, via Berlin, and ultimately via Kiev. He immigrated to New York on the eve of America’s entry into the Second World War, and in that interim six million Jews were immolated in Hitler’s ovens—well over half of all the Jews in the world. Becoming Lubavitch Chief Rebbe in 1950, Schneerson was a refugee from a broken Europe that had devoured itself. Schneerson’s denomination of Hasidism had emerged after the vicious Cossack-led pogroms that punctuated life in 17th-century eastern Europe, when many Jews turned towards the sect’s founder, the Baal Shem Tov. His proper name was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, and his title (often shortened to “Besht”) meant “Master of the Good Name,” for the Baal Shem Tov incorporated Kabbalah into a pietistic movement that enshrined emotion over reason, feeling over logic, experience over philosophy. David Bial writes in Hasidism: A New History that the Besht espoused “a new method of ecstatic joy and a new social structure,” a fervency that lit a candle against persecution’s darkness.

When Schneerson convened a gathering of Lubavitchers in a Brooklyn synagogue for Purim in 1953, a black cloud enveloped the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin was beginning to target Jews whom he implicated in “The Doctor’s Plot,” an invented accusation that Jewish physicians were poisoning Soviet leadership. The state propaganda organ Pravda denounced these supposed members of a “Jewish bourgeois-nationalist organization… The filthy face of this Zionist spy organization, covering up their vicious actions under the mask of charity.” Four gulags were constructed in Siberia, with the understanding that Russian Jews would be deported and perhaps exterminated. Less than a decade after Hitler’s suicide, and Schneerson would look out into the congregation of swaying black-hatted Lubavitchers, and would see a people labeled for extinction.

And so on that evening, Schneerson explicated on the finer points of Talmudic exegesis, on questions of why evil happens in the world, and what man and G-d’s role is in containing that wickedness. Witnesses said that the very countenance of the rabbi was transformed, as he declared that he would speak the words of the living G-d. Enraptured in contemplation, Schneerson connected the Persian courtier Haman’s war against the Jews and Stalin’s upcoming campaign, he invoked G-d’s justice and mercy, and implored the divine to intervene and prevent the Soviet dictator from completing that which Hitler had begun. The Rebbe denounced Stalin as the “evil one,” and as he shouted it was said that his face transformed into a “holy fire.”

Two days later Moscow State Radio announced that Stalin had fallen ill and died. The exact moment of his expiration was when a group of Lubavitch Jews had prayed that G-d would still the hand of the tyrant and punish his iniquities. Several weeks later, and Soviet leadership would admit that the Doctor’s Plot was a government rouse invented by Stalin, and they exonerated all of those who’d been punished as a result of baseless accusations. By the waning days of the Soviet Union, the Lubavitcher Rebbe would address crowds gathered in Red Square by telescreen while the Red Army Band performed Hasidic songs. “Was this not the victory of the Messiah over the dark forces of the evil empire, believers asked?” writes Samuel Heilman and Menachem Friedman in The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

Two days later Moscow State Radio announced that Stalin had fallen ill and died. The exact moment of his expiration was when a group of Lubavitch Jews had prayed that G-d would still the hand of the tyrant and punish his iniquities. Several weeks later, and Soviet leadership would admit that the Doctor’s Plot was a government rouse invented by Stalin, and they exonerated all of those who’d been punished as a result of baseless accusations. By the waning days of the Soviet Union, the Lubavitcher Rebbe would address crowds gathered in Red Square by telescreen while the Red Army Band performed Hasidic songs. “Was this not the victory of the Messiah over the dark forces of the evil empire, believers asked?” writes Samuel Heilman and Menachem Friedman in The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

The Mashiach (“anointed one” in Hebrew) is neither the Son of G-d nor the incarnate G-d, and his goal is arguably more that of liberation than salvation (whatever either term means). Just as Christianity has had many pseudo-messiahs, so is Jewish history littered with figures whom some believers saw as the anointed one (Christianity is merely the most successful of these offshoots). During the Second Jewish-Roman War of the second century, the military commander Simon bar Kokhba was lauded as the messiah, even as his defeat led to Jewish exile from the Holy Land. During the 17th century, the Ottoman Jew Sabbatai Zevi amassed a huge following of devotees who believed him the messiah come to subvert and overthrow the strictures of religious law itself. Zevi was defeated by the Ottomans not through crucifixion, but through conversion (which is much more dispiriting). A century later, and the Polish libertine Jacob Frank would declare that the French Revolution was the apocalypse, that Christianity and Judaism must be synthesized, and that he was the messiah. Compared to them, the Rebbe was positively orthodox (in all senses of the word). He also never claimed to be the messiah.

What all share is the sense that to exist is to be in exile. That is the fundamental lesson and gift of Judaism, born from the particularities of Jewish suffering. Diaspora is not just a political condition, or a social one; diaspora is an existential state. We are all marooned from our proper divinity, shattered off from G-d’s being—alone, disparate, isolated, alienated, atomized, solipsistic. If there is to be any redemption it’s in suturing up those shards, collecting those bits of light cleaved off from the body of G-d when He dwelled in resplendent fullness before the tragedy of creation. Such is the story of going home but never reaching that destination, yet continuing nevertheless. What gives this suffering such beauty, what redeems the brokenness of G-d, is the sense that it’s that very shattering that imbues all of us with holiness. What the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin explains in On the Concept of History as the sacred reality that holds that “every second was the narrow gate, through which the Messiah could enter.”

6.

When the Living God landed at Palisadoes Airport in Kingston, Jamaica, on April 21, 1966, he couldn’t immediately disembark from his Ethiopian Airlines flight from Addis Ababa. More than 100,000 people had gathered at the airport, the air thick with the sticky, sweet smell of ganja, the airstrip so overwhelmed with worshipers come to greet the Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Elect of God, Power of the Trinity, of the House of Solomon, Amhara Branch, noble Ras Tafari Makonnen, that there was a fear the plane itself might tip over. The Ethiopian Emperor, incarnation of Jah and the second coming of Christ, remained in the plane for a few minutes until a local religious leader, the drummer Ras Mortimer Planno, was allowed to organize the emperor’s descent.

Finally, after several tense minutes, the crowd pulled back long enough for the emperor to disembark onto the tarmac, the first time that Selassie would set foot on the fertile soil of Jamaica, a land distant from the Ethiopia that he’d ruled over for 36 years (excluding from 1936 to 1941 when his home country was occupied by the Italian fascists). Jamaica was where he’d first been acknowledged as the messianic promise of the African diaspora. A year after his visit, while being interviewed by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Selassie was asked what he made of the claims of his status. “I told them clearly that I am a man,” he said, “that I am mortal…and that they should never make a mistake in assuming or pretending that a human being is emanated from a deity.” The thing with being a messiah, though, is that it does not depend on the consent of the worshiped whether or not they’re to be adored.

Syncretic and born from the Caribbean experience, and practiced from Kingstown, Jamaica, to Brixton, London, Rastafarianism is a mélange of Christian, Jewish, and uniquely African symbols and beliefs, with its own novel rhetoric concerning oppression and liberation. Popularized throughout the West because of the indelible catchiness of reggae, with its distinctive muted third beat, and the charisma of the musician Bob Marley who was the faith’s most famous ambassador, Rastafarianism is sometime offensively reduced in peoples’ minds to dreadlocks and spliff smoke. Ennis Barrington Edmonds places the faith’s true influence in its proper context, writing in Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers that “the movement has spread around the world, especially among oppressed people of African origins… [among those] suffering some form of oppression and marginalization.”

Syncretic and born from the Caribbean experience, and practiced from Kingstown, Jamaica, to Brixton, London, Rastafarianism is a mélange of Christian, Jewish, and uniquely African symbols and beliefs, with its own novel rhetoric concerning oppression and liberation. Popularized throughout the West because of the indelible catchiness of reggae, with its distinctive muted third beat, and the charisma of the musician Bob Marley who was the faith’s most famous ambassador, Rastafarianism is sometime offensively reduced in peoples’ minds to dreadlocks and spliff smoke. Ennis Barrington Edmonds places the faith’s true influence in its proper context, writing in Rastafari: From Outcasts to Culture Bearers that “the movement has spread around the world, especially among oppressed people of African origins… [among those] suffering some form of oppression and marginalization.”

Central to the narrative of Rastafarianism is the reluctant messiah Selassie, a life-long member of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Selassie’s reign had been prophesized by the Jamaican Protestant evangelist Leonard Howell’s claim that the crowning of an independent Black king in an Africa dominated by European colonialism would mark the dawn of a messianic dispensation. A disciple of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, whom Howell met when both lived in Harlem, the minister read Psalm 68:31’s injunction that “Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God” as being fulfilled in Selassie’s coronation. Some sense of this reverence is imparted by a Rastafarian named Reuben in Emily Robeteau’s Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora who explained that “Ethiopia was never conquered by outside forces. Ethiopia was the only independent country on the continent of Africa…a holy place.” Sacred Ethiopia, the land where the Ark of the Covenant was preserved.

Central to the narrative of Rastafarianism is the reluctant messiah Selassie, a life-long member of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. Selassie’s reign had been prophesized by the Jamaican Protestant evangelist Leonard Howell’s claim that the crowning of an independent Black king in an Africa dominated by European colonialism would mark the dawn of a messianic dispensation. A disciple of Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, whom Howell met when both lived in Harlem, the minister read Psalm 68:31’s injunction that “Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God” as being fulfilled in Selassie’s coronation. Some sense of this reverence is imparted by a Rastafarian named Reuben in Emily Robeteau’s Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora who explained that “Ethiopia was never conquered by outside forces. Ethiopia was the only independent country on the continent of Africa…a holy place.” Sacred Ethiopia, the land where the Ark of the Covenant was preserved.

That the actual Selassie neither embraced Rastafarianism, nor was particularly benevolent in his own rule, and was indeed deposed by a revolutionary Marxist junta, is of no accounting. Rather what threads through Rastafarianism is what Robeateu describes as a “defiant, anticolonialist mind-set, a spirit of protest… and a notion that Africa is the spiritual home to which they are destined to return.” Selassie’s biography bore no similarity to residents in the Trenchtown slum of Kingstown where the veneration of a distant African king began, but his name served as rebellion against all agents of Babylon in the hopes of a new Zion. Rastafarianism found in Selassie the messiah who was needed, and in their faith there is a proud way of spiritually repudiating the horrors of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. What their example reminds us of is that a powerful people have no need of a messiah, that he rather always dwells amongst the dispossessed, regardless of what his name is.

7.

Among the Persian Sufis there is no blasphemy in staining your prayer rug red with shiraz. Popular throughout Iran and into central Asia, where the faith of Zoroaster and Mani had both once been dominant, Sufism drew upon those earlier mystical and poetic traditions and incorporated them into Islam. The faith of the dervishes, the piety of the wali, the Sufi tradition is that of Persian miniatures painted in stunning, colorful detail, of the poetry of Rumi and Hafez. Often shrouded in rough woolen coats and felt caps, the Sufi practice a mystical version of faith that’s not dissimilar to Jewish kabbalah or Christian hermeticism, an inner path that the 20th-century writer Aldous Huxley called the “perennial philosophy.” As with other antinomian faiths, the Sufis often skirt the line of what’s acceptable and what’s forbidden, seeing in heresy intimations of a deep respect for the divine.

A central poetic topoi of Sufi practice is what’s called shath, that is deliberately shocking utterances that exist to shake believers out of pious complacency, to awaken within them that which is subversive about God. One master of the form was Mansour al-Hallaj, born to Persian speaking parents (with a Zoroastrian grandfather) in the ninth century during the Abbasid Caliphate. Where most Sufi masters were content to keep their secrets preserved for initiates, al-Hallaj crafted a movement democratized for the mass of Muslims, while also generating a specialized language for speaking of esoteric truths, expressed in “antithesis, breaking down language into prepositional units, and paradox,” as Husayn ibn Mansur writes in Hallaj: Poems of a Sufi Martyr. Al-Hallaj’s knowledge and piety were deep—he had memorized the Koran by the age of 12 and he prostrated himself before a replica of Mecca’s Kaaba in his Baghdad garden—but so was his commitment to the radicalism of shath. When asked where Allah was, he once replied that the Lord was within his turban; on another occasion he answered that question by saying that God was under his cloak. Finally in 922, borrowing one of the 99 names of God, he declared “I am the Truth.”

A central poetic topoi of Sufi practice is what’s called shath, that is deliberately shocking utterances that exist to shake believers out of pious complacency, to awaken within them that which is subversive about God. One master of the form was Mansour al-Hallaj, born to Persian speaking parents (with a Zoroastrian grandfather) in the ninth century during the Abbasid Caliphate. Where most Sufi masters were content to keep their secrets preserved for initiates, al-Hallaj crafted a movement democratized for the mass of Muslims, while also generating a specialized language for speaking of esoteric truths, expressed in “antithesis, breaking down language into prepositional units, and paradox,” as Husayn ibn Mansur writes in Hallaj: Poems of a Sufi Martyr. Al-Hallaj’s knowledge and piety were deep—he had memorized the Koran by the age of 12 and he prostrated himself before a replica of Mecca’s Kaaba in his Baghdad garden—but so was his commitment to the radicalism of shath. When asked where Allah was, he once replied that the Lord was within his turban; on another occasion he answered that question by saying that God was under his cloak. Finally in 922, borrowing one of the 99 names of God, he declared “I am the Truth.”

The generally tolerant Abbasids decided that something should be done about al-Hallaj, and so he was tied to a post along the Tigris River, repeatedly punched in the face, lashed several times, decapitated, and finally his headless body was hung over the water. His last words were “Akbar al-Hallaj” —“Al-Hallaj is great.” An honorific normally offered for God, but for this self-declared heretical messiah his name and that of the Lord were synonyms. What’s sacrilegious about this might seem clear, save for that al-Hallaj’s Islamic piety was such that he interpreted such a claim as the natural culmination of Tawhid, the strictness of Islamic monotheism pushed to its logical conclusion—there is but one God, and everything is God, and we are all in God. Idries Shah explains the tragic failure of interpretation among religious authorities in The Sufis, writing that the “attempt to express a certain relationship in language not prepared for it causes the expression to be misunderstood.” The court, as is obvious, did not agree.

The generally tolerant Abbasids decided that something should be done about al-Hallaj, and so he was tied to a post along the Tigris River, repeatedly punched in the face, lashed several times, decapitated, and finally his headless body was hung over the water. His last words were “Akbar al-Hallaj” —“Al-Hallaj is great.” An honorific normally offered for God, but for this self-declared heretical messiah his name and that of the Lord were synonyms. What’s sacrilegious about this might seem clear, save for that al-Hallaj’s Islamic piety was such that he interpreted such a claim as the natural culmination of Tawhid, the strictness of Islamic monotheism pushed to its logical conclusion—there is but one God, and everything is God, and we are all in God. Idries Shah explains the tragic failure of interpretation among religious authorities in The Sufis, writing that the “attempt to express a certain relationship in language not prepared for it causes the expression to be misunderstood.” The court, as is obvious, did not agree.

If imagining yourself as the messiah could get you decapitated by the 10th century Abbasids, then in 20th-century Michigan it only got you institutionalized. Al-Hallaj implied that he was the messiah, but for the psychiatric patients in Milton Rokeach’s 1964 study The Three Christs of Ypsilanti each thought that they were the authentic messiah (with much displeasure ensuing when they meet). Based on three years of observation at the Ypsilanti State Hospital starting in 1959, Rokeach treated this trinity of paranoid schizophrenics. Initially Rokeach thought that the meeting of the Christs would disavow them all of their delusions, that the law of logical non-contradiction might mean anything to a psychotic. But the messiahs were steadfast in their faith—each was singular and the others were imposters. Then Rokeach and his graduate students introduced fake messages from other divine beings, in a gambit that the psychiatrist apologized for two decades later and would most definitely land him before an ethics board today. Finally Rokeach grants them the right to their insanities, each of the Christs of Ypsilanti continuing in their merry madness. “It’s only when a man doesn’t feel that he’s a man,” Rokeach concludes, “that he has to be a god.”

If imagining yourself as the messiah could get you decapitated by the 10th century Abbasids, then in 20th-century Michigan it only got you institutionalized. Al-Hallaj implied that he was the messiah, but for the psychiatric patients in Milton Rokeach’s 1964 study The Three Christs of Ypsilanti each thought that they were the authentic messiah (with much displeasure ensuing when they meet). Based on three years of observation at the Ypsilanti State Hospital starting in 1959, Rokeach treated this trinity of paranoid schizophrenics. Initially Rokeach thought that the meeting of the Christs would disavow them all of their delusions, that the law of logical non-contradiction might mean anything to a psychotic. But the messiahs were steadfast in their faith—each was singular and the others were imposters. Then Rokeach and his graduate students introduced fake messages from other divine beings, in a gambit that the psychiatrist apologized for two decades later and would most definitely land him before an ethics board today. Finally Rokeach grants them the right to their insanities, each of the Christs of Ypsilanti continuing in their merry madness. “It’s only when a man doesn’t feel that he’s a man,” Rokeach concludes, “that he has to be a god.”

Maybe. Or maybe the true madness of the Michigan messiahs was that each thought themselves the singular God. They weren’t in error that each of them were the messiah, they were in error by denying that truth in their fellow patients. Al-Hallaj would have understood, declaring before his executioner that “all that matters for the ecstatic is that the Unique shall reduce him to Unity.” The Christs may have benefited more by Sufi treatment than psychotherapy. Clyde Benson, Joseph Cassel, and Leon Gabor all thought themselves to be God, but al-Hallaj knew that he was (and that You reading this are as well). Those three men may have been crazy, but al-Hallaj was a master of what the Buddhist teacher Wes Nisker calls “crazy wisdom.” In his guidebook The Essential Crazy Wisdom, he celebrates the sacraments of “clowns, jesters, tricksters, and holy fools,” who understand that “we live in a world of many illusions, that the emperor has no clothes, and that much of human belief and behavior is ritualized nonsense.” By contrast, the initiate in crazy wisdom, whether gnostic saint of Kabbalist rabbi, Sufi master or Zen monk, prods at false piety to reveal deeper truths underneath. “I saw my Lord with the eye of the heart,” al-Hallaj wrote in one poem, “I asked, ‘Who are You?’/He replied, ‘You.’”

Maybe. Or maybe the true madness of the Michigan messiahs was that each thought themselves the singular God. They weren’t in error that each of them were the messiah, they were in error by denying that truth in their fellow patients. Al-Hallaj would have understood, declaring before his executioner that “all that matters for the ecstatic is that the Unique shall reduce him to Unity.” The Christs may have benefited more by Sufi treatment than psychotherapy. Clyde Benson, Joseph Cassel, and Leon Gabor all thought themselves to be God, but al-Hallaj knew that he was (and that You reading this are as well). Those three men may have been crazy, but al-Hallaj was a master of what the Buddhist teacher Wes Nisker calls “crazy wisdom.” In his guidebook The Essential Crazy Wisdom, he celebrates the sacraments of “clowns, jesters, tricksters, and holy fools,” who understand that “we live in a world of many illusions, that the emperor has no clothes, and that much of human belief and behavior is ritualized nonsense.” By contrast, the initiate in crazy wisdom, whether gnostic saint of Kabbalist rabbi, Sufi master or Zen monk, prods at false piety to reveal deeper truths underneath. “I saw my Lord with the eye of the heart,” al-Hallaj wrote in one poem, “I asked, ‘Who are You?’/He replied, ‘You.’”

8.

“Bob” is the least-likely looking messiah. With his generic handsomeness, his executive hair-cut dyed black and tightly parted on the left, the avuncular pipe that jauntily sticks out of his tight smile, “Bob” looks like a stock image of a 1950’s pater familias (his name is always spelled with quotation marks). Like a clip-art version of Mad Men’s Don Draper, or Utah Sen. Mitt Romney. “Bob” is also not real (which may or may not distinguish him from other messiahs), but rather the central figure in the parody Church of the Sub-Genius. Supposedly a traveling salesman, J.R. “Bob” Dobbs had a vision of JHVH-1 (the central God in the church) in a homemade television set, and he then went on the road to evangelize. Founded by countercultural slacker heroes Ivan Stang and Philo Drummond in 1979 (though each claims that “Bob” was the actual primogeniture), the Church of the SubGenius is a veritable font of crazy wisdom, promoting the anarchist practice of “culture jamming” and parody in the promulgation of a faith where it’s not exactly clear what’s serious and what isn’t.

“Bob” preaches a doctrine of resistance against JHVH-1 (or Jehovah 1), the demiurge who seems as if a cross between Yahweh and a Lovecraftian elder god. JHVH-1 intended for “Bob” to encourage a pragmatic, utilitarian message about the benefits of a work ethic, but contra his square appearance, the messiah preferred to advocate that his followers pursue a quality known as slack. Never clearly defined (though its connotations are obvious), slack is to the Church of the SubGenius what the Tao is to Taoism or the Word is to Christianity, both the font of all reality and that which gives life meaning. Converts to the faith include luminaries like the underground cartoonist Robert Crumb, Pee-wee Herman Show creator Paul Reubens, founder of the Talking Heads David Byrne, and of course Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh. If there is any commandment that most resonates with the emotional tenor of the church, it’s in “Bob’s” holy commandment that says “Fuck ‘em if they can’t take a joke.”

The Church of the SubGenius is oftentimes compared to another parody religion that finds its origins from an identical hippie milieu, though first appearing almost two decades before in 1963, known by the ominous name of Discordianism. Drawing from Hellenic paganism, Discordianism holds as one of its central axioms in the Principia Discordia (written by founders Greg Hill and Kerry Wendell Thornley under the pseudonyms of Malaclypse the Younger and Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst) that the “Aneristic Principle is that of apparent order; the Eristic Principle is that of apparent disorder. Both order and disorder are man made concepts and are artificial divisions of pure chaos, which is a level deeper than is the level of distinction making.” Where other mythological systems see chaos as being tamed and subdued during ages primeval, the pious Discordian understands that disorder and disharmony remain the motivating structure of reality. To that end, the satirical elements—its faux scripture, its faux mythology, and its faux hierarchy—are paradoxically faithful enactments of its central metaphysics.

For those of a conspiratorial bent, Thornley first conceived of the movement after leaving the Marine Corps, and he was an associate of Lee Harvey Oswald. It sounds a little like one of the baroque plots in Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea’s The Illuminatus! Trilogy. A compendium of occult and conspiratorial lore whose narrative complexity recalls James Joyce or Thomas Pynchon, The Illuminatus! Trilogy was an attempt to produce for Discordianism what Dante crafted for Catholicism or John Milton for Protestantism: a work of literature commensurate with theology. Stang and Drummond, it should be said, were avid readers of The Illuminatus! Trilogy. “There are periods of history when the visions of madmen and dope fiends are a better guide to reality than the common-sense interpretation of data available to the so-called normal mind,” writes Wilson. “This is one such period, if you haven’t noticed already.” And how.

For those of a conspiratorial bent, Thornley first conceived of the movement after leaving the Marine Corps, and he was an associate of Lee Harvey Oswald. It sounds a little like one of the baroque plots in Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea’s The Illuminatus! Trilogy. A compendium of occult and conspiratorial lore whose narrative complexity recalls James Joyce or Thomas Pynchon, The Illuminatus! Trilogy was an attempt to produce for Discordianism what Dante crafted for Catholicism or John Milton for Protestantism: a work of literature commensurate with theology. Stang and Drummond, it should be said, were avid readers of The Illuminatus! Trilogy. “There are periods of history when the visions of madmen and dope fiends are a better guide to reality than the common-sense interpretation of data available to the so-called normal mind,” writes Wilson. “This is one such period, if you haven’t noticed already.” And how.

Inventing religions and messiahs wasn’t merely an activity for 20th-century pot smokers. Fearing the uncovering of the Christ who isn’t actually there can be seen as early as the 10th century, when the Iranian war-lord Abu Tahir al-Jannabi wrote about a supposed tract that referenced the “three imposters,” an atheistic denunciation of Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad. This equal opportunity apostasy, attacking all three children of Abraham, haunted monotheism over the subsequent millennium, as the infernal manuscript was attributed to several different figures. In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX said that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had authored such a work (the latter denied it). Within Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century The Decameron there is reference to the “three imposters,” and in the 17th century, Sir Thomas Browne attributed the Italian Protestant refugee Bernardino Orchino with having composed a manifesto against the major monotheistic faiths.

Inventing religions and messiahs wasn’t merely an activity for 20th-century pot smokers. Fearing the uncovering of the Christ who isn’t actually there can be seen as early as the 10th century, when the Iranian war-lord Abu Tahir al-Jannabi wrote about a supposed tract that referenced the “three imposters,” an atheistic denunciation of Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad. This equal opportunity apostasy, attacking all three children of Abraham, haunted monotheism over the subsequent millennium, as the infernal manuscript was attributed to several different figures. In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX said that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had authored such a work (the latter denied it). Within Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century The Decameron there is reference to the “three imposters,” and in the 17th century, Sir Thomas Browne attributed the Italian Protestant refugee Bernardino Orchino with having composed a manifesto against the major monotheistic faiths.

What’s telling is that everyone feared the specter of atheism, but no actual text existed. They were scared of a possibility without an actuality, terrified of a dead God who was still alive. It wouldn’t be until the 18th century that writing would actually be supplied in the form of the French authored anonymous pamphlet of 1719 Treatise of the Three Imposters. That work, going through several different editions over the next century, drew on the naturalistic philosophy of Benedict Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes to argue against the supernatural status of religion. Its author, possibly the bibliographer Prosper Marchand, argued that the “attributes of the Deity are so far beyond the grasp of limited reason, that man must become a God himself before he can comprehend them.” One imagines that the prophets of the Church of the SubGenius and Discordianism, inventors of gods and messiahs aplenty, would concur. “Just because some jackass is an atheist doesn’t mean that his prophets and gods are any less false,” preaches “Bob” in The Book of the SubGenius.

What’s telling is that everyone feared the specter of atheism, but no actual text existed. They were scared of a possibility without an actuality, terrified of a dead God who was still alive. It wouldn’t be until the 18th century that writing would actually be supplied in the form of the French authored anonymous pamphlet of 1719 Treatise of the Three Imposters. That work, going through several different editions over the next century, drew on the naturalistic philosophy of Benedict Spinoza and Thomas Hobbes to argue against the supernatural status of religion. Its author, possibly the bibliographer Prosper Marchand, argued that the “attributes of the Deity are so far beyond the grasp of limited reason, that man must become a God himself before he can comprehend them.” One imagines that the prophets of the Church of the SubGenius and Discordianism, inventors of gods and messiahs aplenty, would concur. “Just because some jackass is an atheist doesn’t mean that his prophets and gods are any less false,” preaches “Bob” in The Book of the SubGenius.

9.

The glistening promise of white-flecked SPAM coated in greasy aspic as it slips out from it’s corrugated blue can, plopping onto a metal plate with a satisfying thud. A pack of Lucky Strikes, with its red circle in a field of white, crinkle of foil framing a raggedly opened end, sprinkle of loose tobacco at the bottom as a last cigarette is fingered out. Heinz Baked Beans, sweet in their tomato gravy, the yellow label with its picture of a keystone slick with the juice from within. Coca-Cola—of course Coca-Cola—its ornate calligraphy on a cherry red can, the saccharine nose pinch within. Products of American capitalism, the greatest and most all-encompassing faith of the modern world, left behind on the Vanuatuan island of Tanna by American servicemen during the Second World War.

More than 1,000 miles northwest from Australia, Tanna was home to airstrips and naval bases, and for the local Melanesians, the 300,000 GIs housed on their island indelibly marked their lives. Certainly the first time most had seen the descent of airplanes from the blue of the sky, the first time most had seen jangling Jeeps careening over the paths of Tanna’s rainforests, the first time most had seen Naval destroyers on the pristine Pacific horizon. Building upon a previous cult that had caused trouble for the jointly administered colonial British-French Condominium, the Melanesians claimed that the precious cargo of the Americans could be accessed through the intercession of a messiah known as John Frum—believed to have possibly been a serviceman who’d introduced himself as “John from Georgia.”

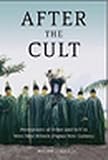

Today the John Frum cult still exists in Tanna. A typical service can include the rising of the flags of the United States, the Marine Corps, and the state of Georgia, while shirtless youths with “USA” painted on their chests march with faux-riffles made out of sticks (other “cargo cults” are more Anglophilic, with one worshiping Prince Philip). Anthropologists first noted the emergence of the John Frum religion in the immediate departure of the Americans, with Melanesians apparently constructing landing strips and air traffic control towers from bamboo, speaking into left-over tin cans as if they were radio controls, all to attract back the quasi-divine Americans and their precious “cargo.” Anthropologist Holger Jebens in After the Cult: Perceptions of Other and Self in West New Britain (Papua New Guinea) describes “cargo cults” as having as their central goal the acquisition of “industrially manufactured Western goods brought by ship or aeroplane, which, from the Melanesian point of view, are likely to have represented a materialization of the superior and initially secret power of the whites.” In this interpretation, the recreated ritual objects molded from bamboo and leaves are offerings to John Frum so that he will return from the heavenly realm of America bearing precious cargo.

Today the John Frum cult still exists in Tanna. A typical service can include the rising of the flags of the United States, the Marine Corps, and the state of Georgia, while shirtless youths with “USA” painted on their chests march with faux-riffles made out of sticks (other “cargo cults” are more Anglophilic, with one worshiping Prince Philip). Anthropologists first noted the emergence of the John Frum religion in the immediate departure of the Americans, with Melanesians apparently constructing landing strips and air traffic control towers from bamboo, speaking into left-over tin cans as if they were radio controls, all to attract back the quasi-divine Americans and their precious “cargo.” Anthropologist Holger Jebens in After the Cult: Perceptions of Other and Self in West New Britain (Papua New Guinea) describes “cargo cults” as having as their central goal the acquisition of “industrially manufactured Western goods brought by ship or aeroplane, which, from the Melanesian point of view, are likely to have represented a materialization of the superior and initially secret power of the whites.” In this interpretation, the recreated ritual objects molded from bamboo and leaves are offerings to John Frum so that he will return from the heavenly realm of America bearing precious cargo.

If all this sounds sort of dodgy, than you’ve reason to feel uncomfortable. More recently, some anthropologists have questioned the utility of the phrase “cargo cult,” and the interpretation of the function of those practices. Much of the previous model, mired in the discipline’s own racist origins, posits the Melanesians and their beliefs as “primitive,” with all of the attendant connotations to that word. In the introduction to Beyond Primitivism: Indigenous Religious Traditions and Modernity, Jacob K. Olupona writes that some scholars have defined the relationship between ourselves and the Vanuatuans by “challenging the notion that there is a fundamental difference between modernity and indigenous beliefs.” Easy for an anthropologist espying the bamboo landing field and assuming that what was being enacted was a type of magical conspicuous consumption, a yearning on the part of the Melanesians to take part in our own self-evidently superior culture. The only thing that’s actually self-evident in such a view, however, is a parochial and supremacist positioning that gives little credit to unique religious practices. Better to borrow the idea of allegory in interpreting the “cargo cults,” both the role which that way of thinking may impact the symbolism of their rituals, but also what those practices could reflect about our own culture.

If all this sounds sort of dodgy, than you’ve reason to feel uncomfortable. More recently, some anthropologists have questioned the utility of the phrase “cargo cult,” and the interpretation of the function of those practices. Much of the previous model, mired in the discipline’s own racist origins, posits the Melanesians and their beliefs as “primitive,” with all of the attendant connotations to that word. In the introduction to Beyond Primitivism: Indigenous Religious Traditions and Modernity, Jacob K. Olupona writes that some scholars have defined the relationship between ourselves and the Vanuatuans by “challenging the notion that there is a fundamental difference between modernity and indigenous beliefs.” Easy for an anthropologist espying the bamboo landing field and assuming that what was being enacted was a type of magical conspicuous consumption, a yearning on the part of the Melanesians to take part in our own self-evidently superior culture. The only thing that’s actually self-evident in such a view, however, is a parochial and supremacist positioning that gives little credit to unique religious practices. Better to borrow the idea of allegory in interpreting the “cargo cults,” both the role which that way of thinking may impact the symbolism of their rituals, but also what those practices could reflect about our own culture.

Peter Worsley writes in The Trumpet Shall Sound: A Study of “Cargo” Cults in Melanesia that “a very large part of world history could be subsumed under the rubric of religious heresies, enthusiastic creeds and utopias,” and this seems accurate. So much of prurient focus is preoccupied with the material faith. Consequently there is a judgment of the John Frum religion as being superficial. Easy for those of us who’ve never been hungry to look down on praying for food, easy for those with access to medicine to pretend that materialism is a vice. Mock praying for SPAM at your own peril; compared to salvation, I at least know what the former is. Christ’s first miracle in the Gospel of John, after all, was the production of loaves and fishes, a prime instance of generating cargo. John Frum, whether he is real or not, is a radical figure, for while a cursory glance at his cult might seem that what he promises is capitalism, it’s actually the exact opposite. For those who pray to John Frum are not asking for work, or labor, or a Protestant work ethic, but rather delivery from bondage; they are asking to be shepherded into a post-scarcity world. John Frum is not intended to deliver us to capitalism, but rather to deliver us from it. John Frum is not an American, but he is from that more perfect America that exists only in the Melanesian spirit.

Peter Worsley writes in The Trumpet Shall Sound: A Study of “Cargo” Cults in Melanesia that “a very large part of world history could be subsumed under the rubric of religious heresies, enthusiastic creeds and utopias,” and this seems accurate. So much of prurient focus is preoccupied with the material faith. Consequently there is a judgment of the John Frum religion as being superficial. Easy for those of us who’ve never been hungry to look down on praying for food, easy for those with access to medicine to pretend that materialism is a vice. Mock praying for SPAM at your own peril; compared to salvation, I at least know what the former is. Christ’s first miracle in the Gospel of John, after all, was the production of loaves and fishes, a prime instance of generating cargo. John Frum, whether he is real or not, is a radical figure, for while a cursory glance at his cult might seem that what he promises is capitalism, it’s actually the exact opposite. For those who pray to John Frum are not asking for work, or labor, or a Protestant work ethic, but rather delivery from bondage; they are asking to be shepherded into a post-scarcity world. John Frum is not intended to deliver us to capitalism, but rather to deliver us from it. John Frum is not an American, but he is from that more perfect America that exists only in the Melanesian spirit.

10.

On Easter of 1300, within the red Romanesque walls of the Cistercian monastery of Chiaravelle, a group of Umiliati Sisters were convened by Maifreda da Pirovano at the grave of the Milanese noblewoman Guglielma. Having passed two decades before, the mysterious Guglielma was possibly the daughter of King Premysl Otakar I of Bohemia, having come to Lombardy with her son following her husband’s death. Wandering the Italian countryside as a beguine, Guglielma preached an idiosyncratic gospel, claiming that she was an incarnation of the Holy Spirit, and that her passing would incur the third historical dispensation, destroying the patriarchal Roman Catholic Church in favor of a final covenant to be administered through women. If Christ was the new Adam come to overturn the Fall, then his bride was Guglielma, the new Eve, who rectified the inequities of the old order and whose saving grace came for humanity, but particularly for women.

Now a gathering of nuns convened at her inauspicious shrine, in robes of ashen gray and scapulars of white. There Maifreda would perform a Mass, transubstantiating the wafer and wine into the body and blood of Christ. The Guglielmites would elect Maifreda the first Pope of their Church. Five hundred years after the supposed election of the apocryphal Pope Joan, and this obscure order of women praying to a Milanese aristocrat would confirm Maifreda as the Holy Mother of their faith. That same year the Inquisition would execute 30 Guglielmites—including la Papessa. “The Spirit blows where it will and you hear the sound of it,” preached Maifreda, “but you know now whence it comes or whither it goes.”

Maifreda was to Guglielma as Paul was to Christ: apostle, theologian, defender, founder. She was the great explicator of the “true God and true human in the female sex…Our Lady is the Holy Spirit.” Strongly influenced by a heretical strain of Franciscans influenced by the Sicilian mystic Joachim of Fiore, Maifreda held that covenantal history could be divided tripartite, with the first era of Law and God the Father, the second of Grace and Christ the Son, and the third and coming age of Love and the Daughter known as the Holy Spirit. Barbara Newman writes in From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature that after Guglielma’s “ascension the Holy Spirit would found a new Church, superseding the corrupt institution in Rome.” For Guglielma’s followers, drawn initially from the aristocrats of Milan but increasingly popular among more lowly women, these doctrines allowed for self-definition and resistance against both Church and society. Guglielma was a messiah and she arrived for women, and her prophet was Maifreda.

Maifreda was to Guglielma as Paul was to Christ: apostle, theologian, defender, founder. She was the great explicator of the “true God and true human in the female sex…Our Lady is the Holy Spirit.” Strongly influenced by a heretical strain of Franciscans influenced by the Sicilian mystic Joachim of Fiore, Maifreda held that covenantal history could be divided tripartite, with the first era of Law and God the Father, the second of Grace and Christ the Son, and the third and coming age of Love and the Daughter known as the Holy Spirit. Barbara Newman writes in From Virile Woman to WomanChrist: Studies in Medieval Religion and Literature that after Guglielma’s “ascension the Holy Spirit would found a new Church, superseding the corrupt institution in Rome.” For Guglielma’s followers, drawn initially from the aristocrats of Milan but increasingly popular among more lowly women, these doctrines allowed for self-definition and resistance against both Church and society. Guglielma was a messiah and she arrived for women, and her prophet was Maifreda.

Writing of Guglielma, Newman says that “According to one witness… she had come in the form of a woman because if she had been male, she would have been killed like Christ, and the whole world would have perished.” In a manner she was killed, some 20 years after her death when her bones were disinterred from Chiaravelle, and they were placed on the pyre where Maifreda would be burnt alongside two of her followers. Pope Boniface VIII would not abide another claimant to the papal throne—especially from a woman. But even while Maifreda would be immolated, the woman to whom she gave the full measure of sacred devotion would endure, albeit at the margins. Within a century Guglielma would be repurposed into St. Guglielma, a pious woman whom suffered under the false accusation of heresy, and who was noted as particularly helpful in interceding against migraines. But her subversive import wasn’t entirely dampened over the generations. When the Renaissance Florentine painter Bonifacio Bembo was commissioned to paint an altarpiece around 1445 in honor of the Council of Florence (an unsuccessful attempt at rapprochement between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches) he depicted God crowning Christ and the Holy Spirit. Christ appears as can be expected, but the Holy Spirit has Guglielma’s face.

Maifreda survived in her own hidden way as well, and also through the helpful intercession of Bembo. The altar that he crafted had been commissioned by members of the powerful Visconti family, leaders in Milan’s anti-papal Ghibelline party, and they also requested the artist to produce 15 decks of Tarot cards. The so-called Visconti-Sforza deck, the oldest surviving example of the form, doesn’t exist in any complete set, having been broken up and distributed to various museums. Several of these cards would enter the collection of the American banker J.P. Morgan, where they’d be stored in his Italianate lower Manhattan mansion. A visitor can see cards from the Visconti-Sforza deck that include the fool in his jester’s cap and mottled pants, the skeletal visage of death, and most mysterious of all, il Papesa—the female Pope. Bembo depicts a regal woman, in ash-gray robes and white scapular, the papal tiara upon her head. In the 1960s, the scholar Gertrude Moakley observed that the female pope’s distinctive dress indicates her order: she was an Umilati. Maifreda herself was first cousins with a Visconti, the family preserving the memory of the female pope in Tarot. On Madison Avenue you can see a messiah who for centuries was shuffled between any number of other figures, never sure of when she might be dealt again. Messiahs are like that, often hidden—and frequently resurrected.

Bonus Links:

—Ten Ways to Live Forever