In July, a friend sent me a link to a BBC article about the division of domestic labor in Indian households: “In millions of middle class homes, the housework is delegated to the hired domestic help…But what happens when the help can’t come to work because there is a nationwide lockdown?” The article goes on the describe the stark imbalance between men and women doing unpaid household work—312 minutes on average a day for women, 29 minutes for men. What the lockdown revealed was that the imbalance has persisted, even in households where both partners have full-time jobs. One woman in Mumbai—who runs a reproductive rights charity—was so fed up, she started a petition (70,000 signatures), imploring the prime minister to publicly admonish men about it.

The article doesn’t address child care specifically, but surely “household labor” includes tending to the needs of children. And it got me thinking about the extent to which the pandemic has impacted family life and parenting here in the U.S.— where patriarchal structures are less prevalent than in more traditional cultures, but affordable child care (either state-provided or in the form of extended family) is typically in short supply.

I am not a parent myself, but mostly everyone around me is. From April to June, I quarantined in suburban Md. with my sister and her two boys, ages nine and 12. My sister already had an equal-time parenting arrangement with her ex-husband—they split the week and alternated weekends. Each of them was working full-time from home and had time “on” and time “off” with my nephews—who are generally homebodies and happy to not go to school. In other words, they had—have—an ideal situation, given the difficult circumstances. But this is more exception than norm.

As summer wore on, and the question of school openings loomed, all the parents I knew grew anxious. They wanted and did not want their children back in school. They wanted real education to resume, but not at the expense of safety. Some parents I sensed did not want to admit how desperate they were to get their non-kid time back, and others were genuinely grateful to be able to spend more quality time with their kids.

Parenting can be isolating; in this moment, much more so. In an attempt to gather voices and struggles of parents during this time, I interviewed three couples—specifically creatives who require significant solitude to do their work—about pandemic parenting over the last eight months. These are all middle-class families with reasonable options, making lemonade out of lemons where they can—and working to be thoughtful about how to steward privileges and cultivate positive transformation during an undeniably wearying, traumatic time for all.

Ed Lin and Cindy Cheung

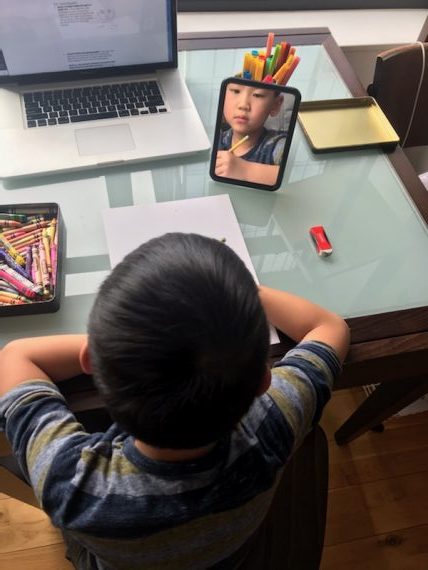

Ed and Cindy live in Brooklyn. They have a seven-year-old son in school remotely, with the option to go partially in-person later in the year if the school deems it safe. They are Asian American. Ed is a novelist and works full-time by day as a journalist (since March in their bedroom). Cindy is an actress (stage and TV).

Cindy: “Out in the living room, I attempt to balance acting work with managing my son’s remote schooling and his many, many, many snacks. There are no other caregivers.”

The biggest change in the structure of their family life is that Cindy is now the full-time school supervisor.

Ed: “Cindy is now basically under house arrest in a second-grade class…There’s no comparison: Cindy has borne the brunt of the changes while I try to dance as hard as I can to satisfactorily perform at the day job.”

Cindy: “From 8 a.m. to 3:45 p.m. I am sort of reliving the second grade through my son’s laptop speakers…I am in the living room all day long acting as my son’s admin assistant, short-order cook, IT manager, teacher, tutor, and playmate. It’s a completely different existence than before.”

In the beginning of the pandemic, this became the new normal, because Cindy’s acting work halted completely (prestige drama watchers, you’ve seen Cindy on Homeland, Billions, House of Cards, 13 Reasons Why, The Affair, et alia). But as online opportunities began to re-open for Cindy, they’ve had to adjust.

Cindy: “Work-wise, I’ve been doing all my auditioning, rehearsing, writing and performing from home…Ed’s lunch hour is one of the few times in the day where I get some time alone and where he and our son hang out. [Also] Ed has taken up my son’s breakfast and bedtime routines, which gives me much-needed time and space at the beginning and end of the day. He also does any dishes that are in the sink from the previous night. I just need to train myself to leave them for him.”

When they talk to other parent-friends, they are aware that people in other parts of the country have more activity options:

Ed: “My brother-in-law’s family in Los Angeles gets in their car and goes to drive-in movies.”

But in general among their peers, they feel everyone is in the same boat:

Cindy: “There are no school situations that are completely satisfying. So much is up in the air. I hear the words ‘crazy,’ ‘unpredictable,’ and ‘unknown’ constantly.”

Both of their creative lives have shifted, suffered, but also blossomed.

Ed: “I used to have 40 minutes or so set aside in the middle of the day to desperately write, and some time at night. The commute to and from work used to mark breathers when I could go into day-job mode and then transition into writing mode. That plan’s scrapped almost completely. I’m writing this now while Cindy’s developing a play via Zoom with her friends. We have Bluetooth headphones now, a necessary item for creatives living in close quarters. I’ve been crazy busy this year, doing final edits on my first YA book, and writing the next book in my Taipei-based mystery series.”

Cindy: “The pandemic has created unexpected blocks of time that allow me to meet regularly with two different creative groups to develop new work. These are made up of artists that I deeply respect and admire and whose company I delight in. Also, they are all usually very busy. Working and being with them has been a surprising gift of this time.”

How have recent acts of racial injustice in the news, protests against police violence, and Black Lives Matter activism affected their parenting?

Ed: “I’ve had a number of Asian-American friends facing racism in the street. My Facebook feed was chock full of incidents…But it also filled with friends protesting for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. It’s past time for our community to recognize that Black lives matter, and that Black men and women are on the whole treated worse by law enforcement…Our focus with our kid hasn’t changed, but we have always focused on diverse books and stories…All I can say is educate yourself, challenge yourself, and never be complacent.”

Cindy: “As a parent, I’ve always been very focused on helping my son develop awareness of how his actions impact others…As for what I’d like to say to your readers…may I suggest this general consideration: If you’re white, make some space, and if you’re a BIPOC, take up more space.”

Sarah Sweeney and Paul Benzon

Sarah and Paul: “We have two kids, a son who is 11 and in sixth grade and a daughter who just turned 17 and is a senior in high school. We live in Saratoga Springs, where we both teach at Skidmore College—Sarah is a digital media artist and professor in the art department and Paul is a professor in the English department. So we both have work schedules that are flexible but full-time. Our kids have been in regular public school since pre-kindergarten, but outside of that, we don’t really have any childcare…Our kids were fully remote last spring, and right now our daughter is fully remote while our son is doing hybrid school, two days a week in person and three days online [they were given a choice, and each chose differently].”

Over the years—really as a result of their work-and-family lives becoming untenable, without the resources for help and without extended family nearby—Sarah and Paul have established an intriguing, and effective, parenting strategy.

Sarah and Paul: “Pre-pandemic, we divided things up very cleanly and carefully: each day of the week, one of us is totally responsible for kids, cooking, activities, the dog, etc. We started dividing things this way when our son was about two and things felt literally, horribly impossible; it was that moment many couples face, when the intensity of exhaustion and resentment threaten the partnership itself, and not everyone makes it through that crucible.

“At this point we have a pretty well-established system, where each of us is either ‘on’ or ‘off’ on a given day. The amazing thing about this is that while you’re around when you’re off, you’re not responsible for anything child-related that happens that day (including cooking or cleaning), and the next day things switch completely. We’ve been able to continue this into the pandemic, and it’s the only reason we’ve both been able to manage and continue our work—it’s relentless for both of us, but it’s equally relentless, and we each have periods of freedom carved out, where we can say to the kids, ‘it’s not my day.’” (Interestingly, Sarah and Paul’s parenting system resembles that of my sister’s “ideal” divorced-parent schedule.)

Sarah and Paul are white, and politically and socially liberal; their upstate college town is largely conservative.

Sarah and Paul: “We’re both confronting these issues [racial injustice] in our workplace and trying to make changes there alongside colleagues and students who are disproportionately impacted…we’re also more conscious of how the absence of a social safety net makes it disproportionately difficult for parents in other social positions to do their work and take care of their kids the way we’re trying to do, even at the basic level of keeping your kids physically safe, whether that’s from contagion or from systemic racialized violence…we’ve spent a lot more time talking with our kids about these issues in the last few months and taking them to demonstrations in town, trying to make sure that they don’t see the issues as isolated or distant.”

While their social circle has shrunk to nil—they’ve chosen to be very cautious, so that they can spend time with elderly family members who are vulnerable—a silver lining for their family has been more weekend family hikes, and Sarah and Paul take daily long walks together. This has improved something that other parents often question about their ‘on/off’ system, which is, when do they spend time together?

Sarah and Paul: “At first it was just to get out of the house, but the walks also allow us to think about joint decisions more and look at the bigger picture of what’s going on in our family and how everyone is doing. We plan to continue that. Having a smaller social circle…has allowed us to connect more and be more mindful of our family unit.

“Beyond our unit, it seems like this moment has done a lot to reveal how much labor goes into parenting, and how unequally the distribution of that labor weighs on women. We’re already seeing changes like widespread wage loss, or career arcs being cut short. (In September, according to an NPR story, 865,000 women—80 percent of the month’s total—left the workforce.) The pandemic has revealed how much of women’s ability to work depends on access to childcare rather than on shared work in the family, and we hope that this moment brings more equality on that front.”

Swati Khurana and Andres Marquez

Swati and Andres have a nine-year-old daughter (and Andres’s 18-year-old daughter lives in South Dakota with her mother). They live in Harlem, but since mid-March they have been sheltering with Swati’s parents upstate. Andres is a public high school teacher, Swati is a visual artist and writer, and she also teaches. They have both been teaching 100 percent remotely, and their daughter, who attends an independent private school, is attending school remotely as well.

Leaving the city was a major change.

Swati: “We miss our life. My kid’s life included playdates after school, Pinkberry treats, riding a scooter home, going to Central park or Riverside Park, and going to her aerial gymnastics studio. I really miss the rhythm of taking my daughter to school, chatting with other parents who have become friends, then doing my own work in cafes or libraries…Not being in our own space has been a great challenge.

Andres: “Additionally, not going into a classroom space and sharing that office camaraderie in the school house has been difficult for me. Sometimes the commute to work or to school would be the few moments of alone/down time that I might get in a week. No longer having the mental stimulation of the drive and the interaction with my students have been really depressing parts of this experience. It feels like Covid’s worst effect has been to cut us all off from one another in such deep and profound ways…Humans are such social animals that not having that means of connection with others has been a terrible circumstance for so many.”

Now living in a multi-generational family situation, the structures of family time have changed, mostly for the better, as household labor is more evenly distributed among more adults.

Swati: “Pre-pandemic, I did the morning and drop-off with the kid. My partner or a babysitter would do pick up and dinner and bedtime. Often, I worked during weeknight dinners. Now, not commuting means that there are times in my evening block of teaching that I can have 30 minutes to an hour of time to eat or at least hang out with my daughter. And with everything shifted, I am around to do much more bedtime rituals than I was prior to the pandemic. Andres is now able to sometimes have lunch with the kid or check in with her during the school day which was impossible before, and after school they play, veg out on TV, and do homework…

“My mother does most of the dinners, and Andres cooks dinner as well sometimes, and other times we get take-out, something that would have been a rarity in both our households prior to Covid. I mostly take care of lunch; sometimes Andres does. This is a huge change from the cafeteria. We are definitely spending a lot more time together.”

Living with extended family has also impacted their activism and their daughter’s engagement with social justice:

Swati: “We are a politically engaged family [Swati has been active in community arts organizations like South Asian Women’s Creative Collective and Asian American Writers’ Workshop]. Being in a non-white multi-racial family and parenting a child who identifies and is identified as Black has been challenging in the post George Floyd murder era…my daughter and her grandfather have been having very important talks about race and the current movement. Perhaps inspired by those talks, my father, an Indian man in his late 60s, went to a Black Lives Matter March in early June, wearing a sign that his grandchild made. And now, as a family we are mailing postcards, letters and doing other efforts to support campaigns for candidates and get out the vote. After sending postcards to young Michigan unregistered voters, the kid double checked the labels on the stamps and asked earnestly, ‘Will this help? Will Trump lose?’ I wish I could’ve said yes. I said, ‘It helps because no matter what happens we know we did our part and we worked hard, and there’s so many people working and doing so much more for the election, so we all have to do our part.”

Like many who are both fortunate and struggling, Swati and Andres are proximal and distant at once to the most difficult pandemic impacts:

Swati: Early in the pandemic, when things were very bad in New York City and hospital beds were scarce, we had a death in the family that we believe was Covid-related, but that was very early on when there were very few tests (in general many death certificates may not specify that deaths are Covid-related). We also had someone in our close circle who was positive for Covid but fortunately showed only mild symptoms, and has recovered. The combination of having both mild and fatal connections to this virus has been illuminating. We have decided…to stay as isolated as possible…

“[B]eing a family that has a foot in both public and private education in New York City, the difference was stark as to how information was relayed, how families and teachers were given opportunities to ask questions and give input. The inequities and disparities have never been starker…From friends, I have heard that many other kids, in schools with much bigger class sizes and less teacher support, had more busywork and less interaction with teachers. From knowing teachers, I heard and saw how much they struggled with helping hundreds of students with their tech support, talking to parents, learning multiple new systems, with very little support.”

In considering whether/how long they will live upstate, Swati and Andres are thankful for options, i.e. they can work remotely or commute to their jobs if necessary.

Swati: “Honestly more than a pandemic, for me, the outcome of the 2020 election, and how neighborhoods and counties outside of New York City vote will make a huge difference and influence any calculation I have around where to live. I am concerned about being around other multi-racial families with Black children, and around non-Black families who believe in #BlackLivesMatter and families who abstain from gun culture.”

Andres makes an interesting, related observation about how “pod-life” has changed his perspective about abstract identity politics versus personal life decisions.

Andres: “It seems easier to take note that narratives around identity and community membership can be limiting in some ways when viewed in juxtaposition to narrative around families of choice, and what it takes to keep that foremost in your decision making. When it comes down to it, the family unit is the most meaningful definer of our identities and public personas that I can imagine.”

In terms of creative work, Swati echoes something Sarah and Paul said about the “constant onslaught of bad news and fear [being] exhausting and distracting in a way that makes it hard to imagine being able to mentally immerse in the way you need to in order to do that work.” (This resonates for me as well—a cumulative fatigue (anxiety, grieving, anger) whose long-term effects I don’t think we can process in real time.)

Swati: “With the pandemic and the trauma of this regime, feeling like the state is failing everywhere around you, I find that I need even more energy for deep reading, writing, and editorial work. One of the biggest challenges is to actually allow myself to rest, to rest my body, my brain, my eyes, my computer battery.”

Andres, on the other hand, is channeling his creative energy productively: according to Swati, he “has started teaching guitar lessons and has been writing music documenting the experience of Covid living” and “has also been writing poetry (about a poem every two days) in the hopes of publishing a short book at some point in the near future.”

So what does the future hold? The changes these families have undergone have been both incremental and drastic; are they permanent? Would they want them to be?

Ed and Cindy think remote learning is gaining a foothold, and possibly for the better.

Cindy: “Parents and students have discovered that remote learning is a much better scenario for them. We all learn differently, and being in the classroom couldn’t have suited everyone in the first place.”

Ed: “Maybe kids can still ‘attend’ school if they’re mildly sick at home…But because of that flexibility, daycare and sitters will see opportunities shrink.”

In higher education, Sarah, who served on the college’s planning task force over the summer, agrees.

Sarah: “While we’ve seen that remote learning takes a toll on students, it also opens up all sorts of opportunities for them—things like virtual tours, collaborations with artists and students from different institutions, and dialogue between people from different areas and cultures, all of which would be much harder to do in a traditional format.”

Swati: “As someone with a physical disability, I would love a world in which virtual meetings and events can coexist with physical ones. Negotiating how to commute to physical events with my mobility issues was extremely challenging…It’s been nice to gather virtually and not have geography be the determination factor. Perhaps also there’s a recognition of how valuable our time is—so many hours lost in a week to commuting for things that may not be the most important…Mostly, I hope this awakening regarding racial and economic inequities that the pandemic exposed continues, gets even bolder and more imaginative.”

***

At my own workplace, we’ve taken to repeating out loud—mostly as a way of deflecting the stress of uncertainty—No one knows anything. But one thing I think is clear from the above accounts and reflections: in real time we have all become more isolated and atomized, and we are experiencing and coping with the pandemic variously. But in the long run, we will emerge with a deeply shared experience and a universal need for grieving, mutual support, concrete paths to positive change, and hope.

Bonus Links:

—On Pandemic and Literature

—Playing with Guns: Parenting in the Age of the Active Shooter

Image Credit: Flickr