When I was six months pregnant, I moved across the world, and I found myself thinking a lot about containers. First, in order to move I had to put everything I owned, including books, into containers. Then those containers had to be loaded into a shipping container that went across the Atlantic. My old life had to be folded and put away in the trunks of memory as I said goodbye to friends, quit a job I was sorry to leave, broke the lease on my one-bedroom apartment, and signed the paperwork for my spousal visa. And in the third trimester, it had become more and more obvious that my body was itself a container—one that was struggling to contain a writhing, wriggling being.

The boxes carrying my things arrived at my new home a few weeks before my due date, and I put my books back on the shelf, not knowing how to organize them. When would I get to read again? As I waited for contractions to start, I read as fast as I could, soaking up the alone time. But it turned out having a baby didn’t mean I couldn’t find time to read. It just meant reading was different. I read on my Kindle app on my iPhone as the baby nursed. I spent long, lonely maternity leave days browsing the shelves at the local library, and then I read my picks while the baby napped.

But what should I read, now that I inhabited this strange, new life? The world was no longer defined by containers—I was outside of all the boxes now, wandering around in a cold new world and watching over a vulnerable, needy being who didn’t know or care what I was thinking about.

I decided to take on a year-long experiment of reading only women authors. My energy to read—and especially to be an engaged, opinionated reader—was dwindling. I wanted to find inspiration and understanding in the voices of other women. It was reductive, I knew, to imagine other women were the solution, but at the same time I craved reductive thinking. I just wanted things to be simple, and to work.

Early in the year, I found a book that let me look inside another new mother’s postpartum mind, and I recognized my own warped perceptions. The book was Little Labors by Rivka Galchen. “She had appeared as an animal,” Galchen writes about her newborn daughter. “A previously undiscovered old-world monkey, but one with whom I could communicate deeply: it was an unsettling, intoxicating, against-nature feeling. A feeling that felt like black magic. We were rarely apart.” Galchen’s book is in fragments, in dream-like observations and factually-presented metaphors that echoed my own disordered internal world. Suddenly, I felt like I was in a container again—a box labeled “Mothers like Rivka Galchen.” I was sure my experiment was working.

Early in the year, I found a book that let me look inside another new mother’s postpartum mind, and I recognized my own warped perceptions. The book was Little Labors by Rivka Galchen. “She had appeared as an animal,” Galchen writes about her newborn daughter. “A previously undiscovered old-world monkey, but one with whom I could communicate deeply: it was an unsettling, intoxicating, against-nature feeling. A feeling that felt like black magic. We were rarely apart.” Galchen’s book is in fragments, in dream-like observations and factually-presented metaphors that echoed my own disordered internal world. Suddenly, I felt like I was in a container again—a box labeled “Mothers like Rivka Galchen.” I was sure my experiment was working.

But right away I found another book that made me just as sure it wasn’t. I read Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women. This book showed me the futility of imagining a single, unified female narrative. I saw the futility of even trying. It was a book I read eagerly, because it promised to tell me something about women’s desire. My own poorly-timed child had been the product of my unruly desires, which I struggled to understand in their aftermath. But after I finished racing through the pages, I was disappointed. I’d seen nothing of myself. I was alienated again; I didn’t fit in to this story. Women talking to women did not create a container in which all women fit.

But right away I found another book that made me just as sure it wasn’t. I read Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women. This book showed me the futility of imagining a single, unified female narrative. I saw the futility of even trying. It was a book I read eagerly, because it promised to tell me something about women’s desire. My own poorly-timed child had been the product of my unruly desires, which I struggled to understand in their aftermath. But after I finished racing through the pages, I was disappointed. I’d seen nothing of myself. I was alienated again; I didn’t fit in to this story. Women talking to women did not create a container in which all women fit.

I read Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and I felt an old, familiar container opening back up again, like an inviting little side door on my slog towards the dim light at the end of the tunnel. This was the familiar feeling of geeking out over a new writer (even if I’d come late to the party on this one). It was like I was 17 and holding the first issue of the Believer magazine all over again. The escapism of fandom was intoxicating. The narrator of this book cloistered herself in her Upper East Side apartment and dulled her days with sleeping pills. I was away from society, too, pushing my baby around in a stroller through our deserted, November-dark suburb, so empty during the weekdays that it was like a post-apocalyptic dystopia. I’d see another mother pushing a baby on the horizon and we’d skitter away from each other like dead leaves, rather than risk interaction. I related to My Year of Rest and Relaxation and I was in awe of My Year of Rest and Relaxation. It felt good to care about something like that again.

I read Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and I felt an old, familiar container opening back up again, like an inviting little side door on my slog towards the dim light at the end of the tunnel. This was the familiar feeling of geeking out over a new writer (even if I’d come late to the party on this one). It was like I was 17 and holding the first issue of the Believer magazine all over again. The escapism of fandom was intoxicating. The narrator of this book cloistered herself in her Upper East Side apartment and dulled her days with sleeping pills. I was away from society, too, pushing my baby around in a stroller through our deserted, November-dark suburb, so empty during the weekdays that it was like a post-apocalyptic dystopia. I’d see another mother pushing a baby on the horizon and we’d skitter away from each other like dead leaves, rather than risk interaction. I related to My Year of Rest and Relaxation and I was in awe of My Year of Rest and Relaxation. It felt good to care about something like that again.

I read Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, and I was outraged. This book had been so hyped, was so incredibly, vastly long—and it was so, so bad. Again, it felt good to care. It felt good to be invested enough to be outraged. The rage I felt at having completed such a frustrating and deeply problematic tragedy/fantasy was a healthy, jumping-jacks kind of rage.

I read Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, and I was outraged. This book had been so hyped, was so incredibly, vastly long—and it was so, so bad. Again, it felt good to care. It felt good to be invested enough to be outraged. The rage I felt at having completed such a frustrating and deeply problematic tragedy/fantasy was a healthy, jumping-jacks kind of rage.

I read How Not to Hate Your Husband After Kids by Jancee Dunn and The Book You Wish your Parents Had Read by Phillipa Perry, and I thought both were helpful, but that both also needed to be read my husband for their strategies to work. Suddenly the idea of women’s self-help seemed like an unfair racket: women lecturing women about how we could help ourselves, I thought, as if we existed in a vacuum. It was depressing, and the opposite of escapism. It made the world harsh again. I needed a balance, I thought, between escaping to contained pockets of my old life and crashing into the boundless difficulties of my new one.

I read How Not to Hate Your Husband After Kids by Jancee Dunn and The Book You Wish your Parents Had Read by Phillipa Perry, and I thought both were helpful, but that both also needed to be read my husband for their strategies to work. Suddenly the idea of women’s self-help seemed like an unfair racket: women lecturing women about how we could help ourselves, I thought, as if we existed in a vacuum. It was depressing, and the opposite of escapism. It made the world harsh again. I needed a balance, I thought, between escaping to contained pockets of my old life and crashing into the boundless difficulties of my new one.

I read Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney (I loved it, I devoured it, but I could barely remember being 19 and it made me feel like I’d wasted my life). I read The Idiot by Elif Batuman (same, pretty much, although it made me glad not to be 19 anymore, instead of regretful). I read My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite and What I Know About Love by Dolly Alderton.

I read Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney (I loved it, I devoured it, but I could barely remember being 19 and it made me feel like I’d wasted my life). I read The Idiot by Elif Batuman (same, pretty much, although it made me glad not to be 19 anymore, instead of regretful). I read My Sister the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite and What I Know About Love by Dolly Alderton.

The year wore on, and the days began bringing our suburb a buttery June light, and my son saw trees with leaves for the first time, and I found something that helped. I began to read collections of essays that used the authors’ stories to talk about the stories of the wider world, and vice versa. These were The Collected Schizophrenias by Esme Weijun Wang, Against Memoir by Michelle Tea, Coventry by Rachel Cusk, and Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino. Once I read one, the rest dominoed after. In these essays, I heard women speaking about themselves and their own stories, without any trace of self-absorption or self-pity.

The year wore on, and the days began bringing our suburb a buttery June light, and my son saw trees with leaves for the first time, and I found something that helped. I began to read collections of essays that used the authors’ stories to talk about the stories of the wider world, and vice versa. These were The Collected Schizophrenias by Esme Weijun Wang, Against Memoir by Michelle Tea, Coventry by Rachel Cusk, and Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino. Once I read one, the rest dominoed after. In these essays, I heard women speaking about themselves and their own stories, without any trace of self-absorption or self-pity.

Wang writes about her experiences with a type of schizophrenia, and then weaves the history and experience of others with schizophrenia into, out of, and around her story. Cusk writes about her parents giving her the silent treatment, and her sadness about the difficulties of mothering adolescents, with an unemotional clarity that gives a kind of grounded, factual comfort to these painful experiences.

It was as though the essayists were opening and shutting a door to the outside world as they wrote, letting its weather into their internal world. At other times, they stood outside themselves and looked in through their windows. The interior and exterior were distinct, and there was a power in the dramatic, architectural interplay created between the two. I luxuriated in the richness of these essays, and I was inspired. I wanted to write about my own journey, my difficulty with motherhood, and my new country. Most of all, I wanted to feel the solidity of knowing how to talk about these things: to paint a square picture with black-and-white lines, then to run colors all over the top, creating something both coherent and ambiguous. Wanting to do that didn’t mean I knew how to, yet. But it was a start.

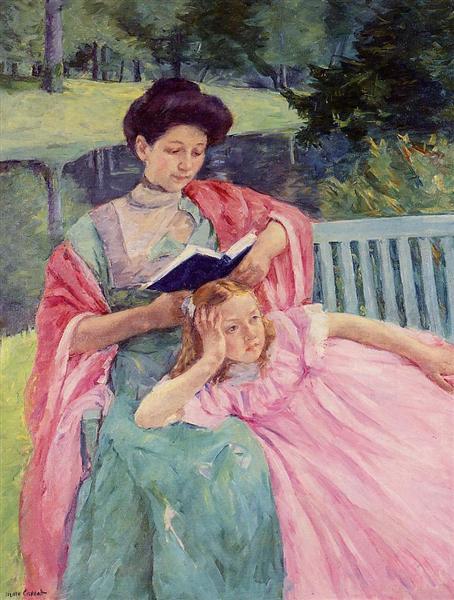

Image Credit: WikiArt.