Here are four notable books of poetry publishing this month.

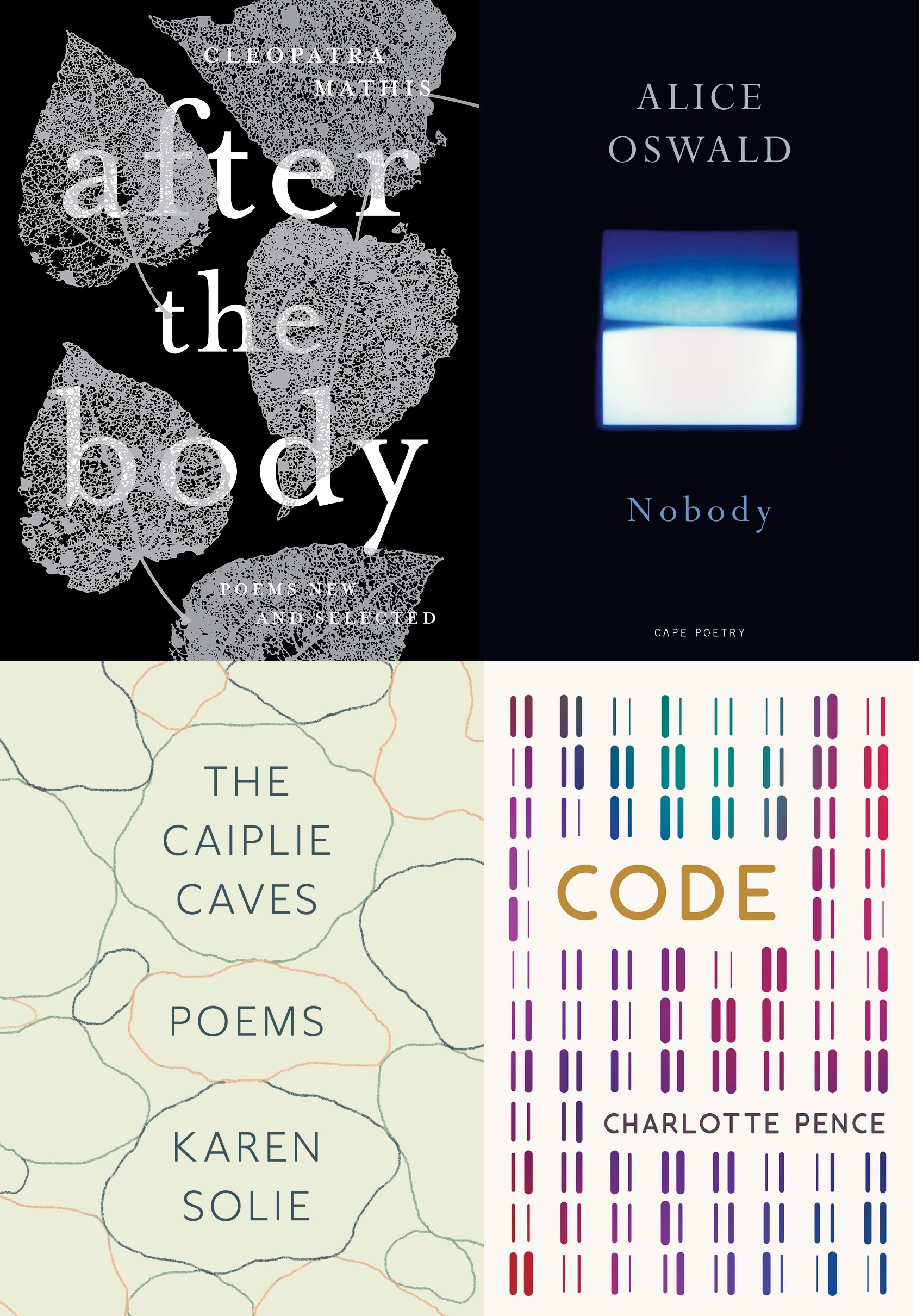

After the Body: Poems New and Selected by Cleopatra Mathis

An excellent collection that leads with her new poems, finely attuned to the body and aging. “Bed-Bound” begins: “I live in the seam of stitches and throb.” The narrator wakes to hear the “insistent / ceiling fan above, dull blade / covered with detritus, spinning / to a vague thunder.” Mathis knows the power of pacing and line breaks. “Time creeps”: a phrase stabbed in the middle ground of the poem. “The storm of tiny bugs / the heat brought in, hovering / over the skin of pockmarked fruit.” The narrator quarantined, with “nothing but pain to consider.” Time will pass. Bodies will age. Yet: “it is patient— / so patient, pain is.” The theme returns in “After Chemo,” when mice “took the house” because they “never expected me back.” “My house is a sieve. In and out they go / with sunflower hulls, cartilage bits, / nesting, nesting.” Mathis considers aging further in “Not Myself”: “For the first time, I could see a link / between me and all the other / impossibly dead, or the one who had gripped the dead / in their arms.” There is an elegiac strain to these new poems: a mother bemoaning the passing of her elders, lamenting the turn of her own body, hoping for a long life for the young. Readers new to Mathis will appreciate her selected work that follows the more recent material. “The Perfect Service” is one of several great poems about parenting: “The truth is, the child protects me, takes away / the obligation to be someone other than myself.” The narrator watches her child move in the spring, “his clumsy feet / hidden in the grass, his fat palms in the thick / clumps of narcissus, everything’s naked.” She wonders how “he might disappear / if I turn my back.” Her child would enfold into the world, escape, but “what about me, / how could I face all this beauty in his absence?” Other selected pieces ponder nature and death—inevitable processes. “In Lent”: a deer dies near a gate. “Do I have to watch it be eaten? Do I have to see / who comes first, who quarrels, who stays?” She wonders “which flesh preferred by which creature— / which sinew and fat, the organs, the eyes.” Mathis suggests that we are surrounded by ferocious appetites. “And I hear the crows, complaint, complaint / splitting the morning, hunched over the skull. / They know their offices.”

Nobody: A Rhapsody to Homer by Alice Oswald

A hazy, mysterious, transporting book by the Oxford professor. Oswald’s epigraph notes that when Agamemnon journeyed to Troy, he paid a poet to watch his wife, but the poet was rowed to a stony island. The bard has drifted, off-course and forgotten: left “as a lump of food for the birds.” The book is suffused with a shifty, macabre feel of disembodied spirits and chants, an ingenious method of capturing the eerie sea. Oswald captures the feel in her lines: “As the mind flutters in a man who has travelled widely / and his quick-winged eyes land everywhere.” Even stories “flutter about / as fast as torchlight.” Fate speaks of the poet stranded on a stony island, where “he paces there as dry as an ashtray,” blithering errant poems, watched skeptically by the sea-crows: “what does it matter what he sings.” Oswald’s description sings throughout. Seals breathe out “the sea’s bad breath / snuffle about all afternoon in sleeping bags.” A little dazed ourselves, we can easily imagine “hundreds of these broken and dropped-open mouths / sulking and full of silt on the seabed.” Among this ancient world, Oswald drops prescient lines: “there are people still going about their work / unfurling sails and loosening knots / it’s as if they didn’t know they were drowned.” A purgatorial sense pervades the poem, capturing the terrible and magnificent sea: “a man is a nobody underneath a big wave / his loneliness expands his hair floats out like seaweed / and when he surfaces his head full of green water / sitting alone on his raft in the middle of death.” I can’t help but think of Yeats’s Spiritus Mundi here, a wild vastness beyond us: “Let me tell you what the sea does / to those who live by it first it shrinks then it / hardens and simplifies and half-buries us / and sometimes you find us shivering in museums.”

The Caiplie Caves by Karen Solie

“In terms of poetics and philosophy,” Solie has said during an interview, “I do find the limit of language a profound and powerful zone. It’s where failure becomes energy.” The Caiplie Caves ponders that zone of linguistic border and failure, especially what happens when we see the progression of a narrator’s ruminations. The collection begins with a prefatory note that tells the story of Ethernan, a 7th-century Irish monk who went to the Caiplie Caves in Scotland “in order to decide whether to commit to a hermit’s solitude or establish a priory on May Island. This choice, between life as a ‘contemplative’ or as an ‘active.’” Framed and interspersed with these monastic contemplations, many poems in the collection are anchored in the contemporary. The interplay between imagined past and literary present creates a rich effect. The contemporary sections are rife with great lines: “My many regrets have become the great passion of my life.” Others stir with their figurative language: “but for the banks of wild roses, the poppies you loved // parked like an ambulance by the barley field.” Solie’s verse feels operatic at points: “Our culture is best described as heroic. / Courageous in self-promotion, noble / in the circulation of others’ disgrace, // its preoccupation with death in a context of immortal glory / truly epic, and the task becomes to keep / the particulars in motion // lest they settle into categories whose opera / is bad infinity.” Among these present concerns, Ethernan continues to contemplate, often with wit: “In this foggy, dispute-ridden landscape // thus begins my apprenticeship to cowardice.” He is not the type of person “who leads others into battle // or inspires love.” The devil is in the discernment: “if one asks for a sign // must one accept what’s given?” After all, “I wanted an answer, not a choice.” Ethernan’s life is long gone, but his spirit allows Solie to make contemplation a form of haunting: “I have outlived my future, why invite its ghosts // to bother me where I sleep?”

Code by Charlotte Pence

A book suffused with genuine optimism—without sentimentality. An early poem in the collection, “The Weight of the Sun,” sets the pensive stage. The narrator is “tilting / the rocking chair back and forth / with my toes,” a rhythm that carries her through a 4 a.m. feeding. She looks outside, and wonders if “everyone on this block” is “wishing for sleep, / for peace, for the coming day to be better // than the last. She stares at the blades of grass; realizes that a red fox “is the one who / flattens the path through the lawn.” Her mind wanders: “Behind every square of light flipped on, / someone is standing or slouching, // stretching of sighing, covering / or uncovering her face.” Other poems, like “While Reading About Semiotics,” deliver sharp moments of dread, as when a cottonmouth seethes, rushing toward her “with its wide ghost of throat.” It’s a great, odd image. Pence often has a pleasantly sideways manner of looking and layering, as in “Lightening,” which plays with the multiple connotations of the word. “You are dropping, / my baby. Twisting / your way down.” The word, the narrator notes, is also used to describe “the moment before / death. Another release.” Yet there’s no etymological explanation “for such a linguistic hike.” She wonders this wordplay while walking “these brown woods / where deer thin / to vines.” Similar playfulness exists in the meandering “Zwerp”: “Three mud- / puddle frogs // leap-flee / from me.” The frogs “take light — / blur it, bold it — / with long, slick / legs, all muscle // memory / of place and space.” One late poem, “I’m Thinking Again of That Lone Boxer,” reveals her range in subject and style. The narrator watches a man boxing in Baltimore’s Herring Run Park: “City gridlock stood / beside him as he slipped and bobbed, countered / and angled.” She thinks for a moment about herself, about motherhood, but is drawn to the man’s precise swings. She won’t call him a dancer; he’s “a man fighting in an empty / field against himself,” and the sight stirs her: despite him being ready to land or receive a punch, “how / can I not believe in the possibility of peace?”