1.

You could say that pandemic quarantine has compressed our lives from three dimensions into two: we hear voices but don’t see faces; we see faces, but without bodies; we see bodies, but in rectangular frames and on a flat screen, absent the feel or smell or vibrations of them. We scroll through videos, but of course even the most impromptu “reality” iPhone shoots are composed—timed and captured for specific purpose, to tell a particular story. For those of us already at odds with social media—its brevity and pacing, its bent for surface more than depth—human interaction during lockdown can feel like a lot of performance and exhibition: like driving through quarantine country, looking out the passenger window, and every so often murmuring, Isn’t that lovely. Isn’t that awful. Are we there yet?

On the other hand, if you are fortunate to have at-home stability, and a measure of solitude, there is also a lot of time—for peeling back surfaces and investigating depths, making new discoveries.

Who ever knows why or how we fall down certain rabbit holes. Often it starts with a basic need or instinct—in my case, escape into romanticism. Late at night, after full telework-and-family days, I started watching old movies, golden age stuff of the ‘30s and ‘40s—Hitchcock, Stevens, Mankiewicz; Curtiz, Hawks, Huston. It started with Bogie, whose appeal I used to scoff at (in favor of pretty faces like Gregory Peck and Gary Cooper) but now suddenly “got.” I’d seen some greatest hits—The Maltese Falcon, Sabrina, Casablanca—but watched for the first time The Petrified Forest, The African Queen, Beat the Devil, High Sierra. Once I got to To Have and Have Not, I had to pivot to Bogie & Bacall: four films together in five years, that undeniable, intriguing chemistry. (That one off year, 1945, was the year Bogie sorted out his messy, unhappy marriage to Mayo Methot, and Bogie & Bacall got hitched.) I rewatched The Big Sleep, then on to Key Largo and Dark Passage in one sitting.

Who ever knows why or how we fall down certain rabbit holes. Often it starts with a basic need or instinct—in my case, escape into romanticism. Late at night, after full telework-and-family days, I started watching old movies, golden age stuff of the ‘30s and ‘40s—Hitchcock, Stevens, Mankiewicz; Curtiz, Hawks, Huston. It started with Bogie, whose appeal I used to scoff at (in favor of pretty faces like Gregory Peck and Gary Cooper) but now suddenly “got.” I’d seen some greatest hits—The Maltese Falcon, Sabrina, Casablanca—but watched for the first time The Petrified Forest, The African Queen, Beat the Devil, High Sierra. Once I got to To Have and Have Not, I had to pivot to Bogie & Bacall: four films together in five years, that undeniable, intriguing chemistry. (That one off year, 1945, was the year Bogie sorted out his messy, unhappy marriage to Mayo Methot, and Bogie & Bacall got hitched.) I rewatched The Big Sleep, then on to Key Largo and Dark Passage in one sitting.

Finally, it was all about Lauren Bacall.

I sunk in deeply, hours and hours with her lesser known filmography: she appeared in nearly 60 films (you’re welcome, Amazon Prime). Then I began digging into her life, the woman behind the glam and romance, behind that feline allure and femme-fatale voice. With a film, stage, and TV career that spanned nearly 70 active years; three memoirs (the first of which won the National Book Award); and a rich personal and family life, only 12 of which involved Bogie; there was much to discover. My lockdown has been at times lonely, but notably less so with Bacall’s company.

2.

Born Betty Perske in 1924 in the Bronx, you could paint Bacall’s life as charmed and destined from the get-go—no late bloomer when it came to ambition. But the thing about a rapid early rise: what goes up must come down. The road following early success is inevitably a rocky one, if for no other reason than—if you are blessed with good health and many years, as Bacall was—it’s a long one.

As a teen, Betty and a friend would skip school and go to the movies, where Betty fell hard for her first love, the other Bette (Davis). Those mesmerizing afternoons in movie houses made clear to her that she needed to be an actor. Bacall’s mother Natalie (née Natalie Weinstein Bacal) was both pragmatic—a Jewish immigrant from Romania and single mother by the time her daughter was six—and a vicarious dreamer. Thus she fully supported her only child’s ambitions. At 16, Betty enrolled at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she immersed herself in the craft of stage acting. “They stressed self-discovery—studying life, as that was what acting was all about,” Bacall wrote in By Myself and then Some. “How to use one’s body to project emotions…My days were full and near perfect that year.” There also she met Kirk Douglas, a few years ahead of her, who became a short-lived beau, then later a colleague and lifelong friend.

As a teen, Betty and a friend would skip school and go to the movies, where Betty fell hard for her first love, the other Bette (Davis). Those mesmerizing afternoons in movie houses made clear to her that she needed to be an actor. Bacall’s mother Natalie (née Natalie Weinstein Bacal) was both pragmatic—a Jewish immigrant from Romania and single mother by the time her daughter was six—and a vicarious dreamer. Thus she fully supported her only child’s ambitions. At 16, Betty enrolled at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where she immersed herself in the craft of stage acting. “They stressed self-discovery—studying life, as that was what acting was all about,” Bacall wrote in By Myself and then Some. “How to use one’s body to project emotions…My days were full and near perfect that year.” There also she met Kirk Douglas, a few years ahead of her, who became a short-lived beau, then later a colleague and lifelong friend.

At 17, when money for acting school ran out, Betty starting working as a model for agencies in the garment district. She also started selling Actors’ Cue magazine outside Sardi’s, where she met (accosted) influential Broadway folk, including producer Max Gordon, who liked her pluck and kept an open-door policy for her, and actor Paul Lukas, who became a mentor. She then started working as a theater usher on Broadway—anything to be in/near the world of acting, and to have days free to pound the pavement for auditions. By the time she had her first walk-on Broadway role, she had taken her mother’s second name and added an extra “l.” Her first substantial role in the theater (thanks to Max Gordon, who brought her in for an audition) was in George S. Kaufman’s Franklin Street. The play opened in Wilmington to mixed reviews and never made it to Broadway. Betty was still just 17, disappointed but unfazed. “Funny how you get the feeling that once you have a part in a play the work will never stop,” she wrote. “Was that ever a wrong feeling, as I would spend the next 30 years discovering.”

The next year, she went with her mother and her Aunt Rosalie to see Casablanca. Her aunt loved Bogie, thought him sexy and charismatic, but Betty didn’t see it; he was no Leslie Howard, she thought.

At 18, Bacall met an editor at Harper’s Bazaar, who in turn set up a meeting for her with Diana Vreeland. Vreeland asked her to come in for a shoot; she saw something in Betty, a glamor that Betty herself did not see. She appeared in Harper’s several times that year, and in 1943 made the cover. Inquiries came pouring in—David O. Selznick, Columbia Pictures, Howard Hughes—but the most appealing offer came from director Howard Hawks, whose tough-talking wife, Slim, had seen the Harper’s cover and encouraged Hawks to track her down. Bacall’s Uncle Jack, a lawyer for Look magazine, advised and encouraged her move to California for the screen test—six to eight weeks in L.A., with the potential for a personal contract with Hawks, who by then had made Only Angels Have Wings, Bringing Up Baby, and other well-known films. And so she went, across the country alone, at age 19—still starry-eyed, and very much a naïve kid.

From there it was a whirlwind, then a rocket-ship launch to both stardom and one of Hollywood’s greatest love stories: playing an assertive and sexy drifter in the screen adaptation of Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not—a character fashioned after Slim Hawkes and nicknamed Slim by Bogart’s character—Betty Bacall, stage-named Lauren now, dropped her chin, raised her eyes (all this in fact to control the nervous tremble of her head), and suggested to Bogart’s character that he put your lips together and blow. The rest, as they say, is history.

3.

Fast forward now, through the years familiar to most of us: love, marriage, two Bogart children; those three films together after To Have and Have Not; a fabulous Hollywood life, friendships with the likes of Sinatra and John Huston, Katie Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, Vivien Leigh, Dick Powell and June Allyson, novelist Louis Bromfield, the Gershwins; and lots of time sailing on Bogie’s beloved boat Santana. During that decade, Bogie made The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen (for which he won the Oscar), The Caine Mutiny (nominated for the Oscar), and The Barefoot Contessa, among many other films.

Meanwhile Bacall garnered a reputation in Hollywood for being difficult (i.e., she spoke her mind, then was deemed a bitch for it, even suspended from contracts), as she turned down what she felt were bad scripts or bad fits. She’d become gun shy after her first film following To Have and Have Not, Confidential Agent, bombed—sending her Hollywood stock plummeting in an instant. Still she managed to make Young Man with a Horn (with old friend Kirk Douglas), How to Marry a Millionaire, Written on the Wind, and Designing Woman—dramas and comedies alike. Millionaire and Designing Woman were especially well received, though I myself recommend the less-lauded Young Man with a Horn—in which Bacall plays a lesbian, scripted evasively (the only option in Hollywood in 1950) as a woman who is “sick” in her romantic relationships, “a strange girl” and “complicated.”

Meanwhile Bacall garnered a reputation in Hollywood for being difficult (i.e., she spoke her mind, then was deemed a bitch for it, even suspended from contracts), as she turned down what she felt were bad scripts or bad fits. She’d become gun shy after her first film following To Have and Have Not, Confidential Agent, bombed—sending her Hollywood stock plummeting in an instant. Still she managed to make Young Man with a Horn (with old friend Kirk Douglas), How to Marry a Millionaire, Written on the Wind, and Designing Woman—dramas and comedies alike. Millionaire and Designing Woman were especially well received, though I myself recommend the less-lauded Young Man with a Horn—in which Bacall plays a lesbian, scripted evasively (the only option in Hollywood in 1950) as a woman who is “sick” in her romantic relationships, “a strange girl” and “complicated.”

Bacall devoted herself during this time to the roles of wife and mother. By her own account, her marriage to Bogie did and did not affect her career: he made her promise to put family before work, which she did willingly. Apart from this commitment to priorities, he neither intervened (she was already contending with being “Mrs. Bogart”) nor interfered with her professional choices. The work-family balance and traditional gender roles fulfilled them both: Bacall was, after all, just 20—still a virgin in fact—when she married Bogie; he was 46, experienced in life, love, and the actor’s vocation: “[F]or twelve and a half years he was, among many other things, my teacher,” she wrote. “He taught me his philosophy of life. He taught me the rules of the Hollywood game…He taught me about standards and the price one must pay to keep those standards high. He taught me about the value of work and the importance of truth and character.”

They had, for the most part, a beautiful life together. They were surrounded by talented, interesting people. “What a good time of life that was,” Bacall wrote, about both work and friendships. “The best people at their best.” In the early 1950s, Bacall also explored a different side of herself by becoming involved in politics—as a member of the anti-HUAC Committee for the First Amendment, and also as an ardent supporter and friend of Adlai Stevenson.

A good time of life. And yet: what goes up must come down. In 1956, it all came to a screeching halt. Bogie was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died in 1957, at age 58. Bacall, age 33, was alone, bereft, mother of two. Her career was middling, stalled to some degree. The fifth Bogie & Bacall film, Melville Goodwin, USA, was never to be.

4.

This is where Bacall becomes most interesting to me. I love the love story, don’t get me wrong—I came looking for escapist romance after all. But, what did Lauren Bacall do when everything came tumbling down? When the sepia dream came to an end, and she awoke to a harsh new reality?

Well, she made mistakes. Two relationships we know of, the first with Frank Sinatra—a dodged bullet, as she tells it. He was an old friend whom she leaned on for solace and then nearly married (he backed out, in response to unleashed press attention, for which he unjustly blamed her). The second, with then-stage actor Jason Robards, sent up all the red flags—alcoholism, all-night carousing, plus he was married—but she was determined to “save” him from the unhappiness she decided was the source of his drinking. “Having lived through a few relationships, I do know now that I’ve endowed the men in my life with the qualities I wished them to have, rejecting whatever qualities they actually possessed that interfered with my romantic notions…once I found Jason and made up my mind that this was what I had to have, I would not give up. Utter tenacity.” They married in 1961, and quickly had a son, Sam (now an actor). Robards did not change. The relationship remained rocky, though they stayed married eight years.

Professionally, though, Bacall finally began tending to and following her gut ambitions. She’d wandered Europe while recovering from Bogie’s death, and took a good role in J. Lee Thompson’s Flame Over India, which brought her to London and Rajasthan. When that was done, she had decisions to make about the next phase of her life and reconnected with her love for the stage. She got an offer to do George Axelrod’s comedy Goodbye, Charlie on Broadway (basically a bomb, but she herself was well reviewed), and with that moved back to New York, where she lived—solo, after her divorce from Robards—for the rest of her life.

Professionally, though, Bacall finally began tending to and following her gut ambitions. She’d wandered Europe while recovering from Bogie’s death, and took a good role in J. Lee Thompson’s Flame Over India, which brought her to London and Rajasthan. When that was done, she had decisions to make about the next phase of her life and reconnected with her love for the stage. She got an offer to do George Axelrod’s comedy Goodbye, Charlie on Broadway (basically a bomb, but she herself was well reviewed), and with that moved back to New York, where she lived—solo, after her divorce from Robards—for the rest of her life.

Bacall did two movies during that time—a comedic role in Sex and the Single Girl, opposite Henry Fonda, and a dramatic one in Harper, with Paul Newman. But with the move back to New York, the theater became her new, old flame. Her life was beginning anew, though not exactly with the freshness of her youth: on the heels of separation from Robards, followed by her beloved mother’s serious decline in health, came the opportunity to play Margo Channing—Bette Davis’s star role in All About Eve—in the Broadway musical version of the film, Applause. Bacall was 45 years old.

Bacall did two movies during that time—a comedic role in Sex and the Single Girl, opposite Henry Fonda, and a dramatic one in Harper, with Paul Newman. But with the move back to New York, the theater became her new, old flame. Her life was beginning anew, though not exactly with the freshness of her youth: on the heels of separation from Robards, followed by her beloved mother’s serious decline in health, came the opportunity to play Margo Channing—Bette Davis’s star role in All About Eve—in the Broadway musical version of the film, Applause. Bacall was 45 years old.

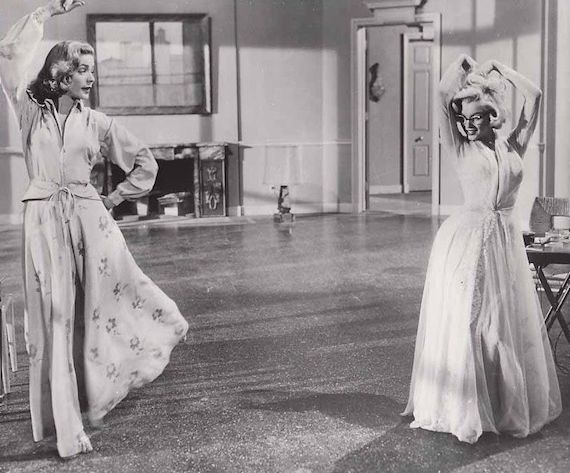

“I’d always been musical. One of my great frustrations had been my inability to sing…could I do it?” She decided she had to find out. “What the hell. With everything else in my life shaken up, might as well go all the way.” Voice lessons, personal training, dance training—she took it all on, building physical stamina, and terrified; but also with less to lose than she’d ever had. And yet, soon came more loss: her divorce was finalized, her beloved mother died, and her son got married. She was alone now, middle aged, and running out of money.

But what then did she do? How did she respond to loss and instability? She threw herself into work, into becoming a star, like she never had: “It would be the first time distractions would be at a minimum…From the time I fell in love with Bogie I had never been able to forget my personal life and zero in on my career. Now I would do it with a vengeance.” And she did. In March 1970, Applause opened on Broadway, to unanimously rave reviews. She won the Tony that year for Best Performance by an Actress in a Musical.

The magic of the theater is the live performance that cannot be reproduced. But I was able to catch grainy bits of recordings of Applause on YouTube, from 1972, when Bacall was 47—my age now. She bursts with life, and also with the gravitas of life experience. Her opening song takes place in a gay bar, where she’s playing hooky from the opening night party after her character’s own stage triumph. Bacall shimmies, kicks, and gyrates, exuberantly but also humorously—she is “too old” for this, and that’s the joy of it.

I feel groggy and weary and tragic

Punchy and bleary and fresh out of magic

But alive, but alive, but alive!I feel twitchy and bitchy and manic

Calm and collected and choking with panic

But alive, but alive, but alive!I’m a thousand different people

Every single one is real

I’ve a million different feelings

OK, but at least I feel!

Clearly—as both character and actor (and woman)—she is having the time of her life.

5.

In her 50s, Bacall appeared in a few movies—Sidney Lumet’s Murder on the Orient Express; The Shootist, John Wayne’s last film; and Robert Altman’s political satire HealtH, in which she plays an absurdly youthful 83-year-old narcoleptic virgin (hilarious and worth seeing). At 54 she published By Myself, which won the National Book Award.

In 1981, at age 57, Bacall returned to Broadway, to star in the musical version of Woman of the Year. Her friend Katharine Hepburn had originated the role of reporter Tess Harding in 1942, at age 35, while Bacall’s Tess was an older, successful broadcast journalist fashioned after Barbara Walters. A decade after Applause, Bacall shone just as brightly. “This star’s elegance is no charade,” wrote Frank Rich in The New York Times, “no mere matter of beautiful looks and gorgeous gowns…As hard and well as Miss Bacall works in ‘Woman of the Year,’ she never lets us see any sweat. That’s why this actress is a natural musical-comedy star.” Watching (again, on YouTube) Bacall’s performance at that year’s Tony’s—she won again for Best Actress in a Musical—is indeed to see an actress at ease. She seems to me more comfortable in her body, more relaxed than we’ve ever seen her, on screen or on stage. No more trembling; she holds her head, and her heart, up high.

6.

If you’re still reading, you won’t be daunted by yet another chapter in Bacall’s life. She just. Kept. Working. In her 60s she performed in a Harold Pinter play, Sweet Bird of Youth, and in a British mini-series, A Foreign Field, with Alec Guinness. In her 70s, she reunited with Robert Altman for Prêt-à-Porter (playing another “Slim”), was nominated for the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Barbra Streisand’s The Mirror Has Two Faces, made one more film with Kirk Douglas (Diamonds), and worked with Lars Von Trier in Dogville as well as its sequel, Manderlay. She also made a bad French film called Day and Night with Alain Delon and Jeanne Moreau, directed by Bernard Henri-Levi, and performed on stage at the Chichester Festival in Friedrich Durrenmatt’s The Visit, which was not a particularly positive experience. At age 83, she played a political wife in Paul Schrader’s critically praised The Walker, which featured a formidable ensemble cast including Kristin Scott Thomas, Woody Harrelson, Lily Tomlin, and Willem Defoe. In these later years, Bacall said yes to working with talented people and always counted these rich and valuable experiences, whether they were hits or flops or somewhere in between.

If you’re still reading, you won’t be daunted by yet another chapter in Bacall’s life. She just. Kept. Working. In her 60s she performed in a Harold Pinter play, Sweet Bird of Youth, and in a British mini-series, A Foreign Field, with Alec Guinness. In her 70s, she reunited with Robert Altman for Prêt-à-Porter (playing another “Slim”), was nominated for the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for Barbra Streisand’s The Mirror Has Two Faces, made one more film with Kirk Douglas (Diamonds), and worked with Lars Von Trier in Dogville as well as its sequel, Manderlay. She also made a bad French film called Day and Night with Alain Delon and Jeanne Moreau, directed by Bernard Henri-Levi, and performed on stage at the Chichester Festival in Friedrich Durrenmatt’s The Visit, which was not a particularly positive experience. At age 83, she played a political wife in Paul Schrader’s critically praised The Walker, which featured a formidable ensemble cast including Kristin Scott Thomas, Woody Harrelson, Lily Tomlin, and Willem Defoe. In these later years, Bacall said yes to working with talented people and always counted these rich and valuable experiences, whether they were hits or flops or somewhere in between.

Herein lies Bacall’s “secret” to a full and meaningful life; to aging well—something I think about often, as a woman in my own “third act.” She was always in it for the love, the experience, the richness; the aliveness of the here and now, the people who animate the work. The dedication for her second book, Now, reads: “To friendship, the relationship I value above all others” (by this time she’d been living alone for more than 30 years). She wanted to do the work she loved, to learn from wonderful and talented people, more than she wanted fame or the glamorous life.

Herein lies Bacall’s “secret” to a full and meaningful life; to aging well—something I think about often, as a woman in my own “third act.” She was always in it for the love, the experience, the richness; the aliveness of the here and now, the people who animate the work. The dedication for her second book, Now, reads: “To friendship, the relationship I value above all others” (by this time she’d been living alone for more than 30 years). She wanted to do the work she loved, to learn from wonderful and talented people, more than she wanted fame or the glamorous life.

It can’t be denied that Betty Perske was extraordinarily lucky. But what is luck, other than a discipline of openness, willingness, alertness to one’s desires, gifts, and limitations. Things can, and do, fall into all of our laps; but we aren’t always paying attention or ready for these miracles. Neither young Betty Perske nor the mature Lauren Bacall took anything for granted—money, her looks, friendships, jobs, support from influential people. When opportunities came her way, she stepped forward, sometimes off a ledge. She worked hard, pushed herself. In her later years, with so much life and success behind her, she still approached her work with humility—deferring to younger actresses like Barbra Streisand and Nicole Kidman, throwing herself into comedic roles where she could easily have made a fool of herself, submitting herself to the risky artistry of directors like Lars von Trier (twice), playing minor roles in all-star ensemble casts.

7.

Was Lauren Bacall a little polyannish? Did she acknowledge only the good stuff and either conceal or deny the messier realities? Some believe that Bogie carried on an affair with his hairdresser, Verita Bouvaire-Thompson, throughout their marriage; some claim Bacall had started her romantic relationship with Frank Sinatra while Bogie was still alive. And what about her old friend Kirk Douglas’s womanizing and alleged rape of Natalie Wood? Did Bacall not care about other people’s bad behavior? Did she keep her nose clean by turning the other way?

I have no idea. Maybe. It makes a difference, but not a big one. People—even celebrities—are entitled to their private failures and inner conflicts. It seems to me undeniable that she and Bogie had a great love. If extramarital relationships were part of that, so be it. People are complicated. Our lovers, friends, family. Bacall ultimately lived many lives and surely was no exception to these human complexities. She seemed only and always to speak positively in public about people she loved and worked closely with, even those we know behaved badly. Maybe she should have denounced the rampant sexism, racism, and homophobia she surely experienced or witnessed in Hollywood. But she chose to keep things close, the most private things private. In her time and place, she would have understood this as both classy and shrewd.

During this strange, upending time, I’ve enjoyed getting to know this elegant, tough, passionate, and vulnerable woman; it’s helped me get to know myself. In the end—or the middle-end, at 60, 70, 80—I hope am able to claim what Bacall wrote in the final words of By Myself:

I have learned that I am a valuable person. I’ve made mistakes, so many mistakes. And will make more, big ones. But I pay. They’re my own…I remain as vulnerable, romantic, and idealistic as I was at 15…I’m not ashamed of what I am, of how I’ve passed through this life. What I am has given me strength to do it…I have a contribution to make. I am not just taking up space in this life. I can add something to the lives I touch. I don’t like everything I know about myself, and I’ll never be satisfied, but nobody’s perfect. I have no idea where the next years will take me, what they will hold, but I’m open to suggestions.

Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons, Pixabay, Needpix.