The only two things that were real in pro wrestling were the money and the miles.

—Chris McCormick, The Gimmicks

Wrestling is true and genuine and great.

—Gabe Habash, Stephen Florida

The figure-four leg lock, my favorite professional wrestling move, is quite simple: spread apart the legs of your supine opponent; wrap yourself around his left leg and bend it over his outstretched right leg; fall to the ground and push down on your opponent’s left foot. His histrionic wailing will indicate that you have executed the move successfully. (Here’s how a master does it.)

From the description above, it is perhaps evident that the figure-four requires a certain level of cooperation from the victim, who patiently waits as you pretzel him into agony. As a young fan of professional wrestling who would practice the move and others with my best friend, I loved this choreographed compliance—a compliance always in the service of storytelling, be it our basement role playing or the soap operatic spectacle of WrestleMania. When I signed up for actual wrestling, in which the opponents were decidedly incompliant, I found it less satisfying. The drama was too stark, though I did begrudgingly appreciate the brute elegance with which a superior opponent could bend my body to his will. I soon took up cross-country running.

Though I abandoned the sport and my pro wrestling fandom waned, I was excited to see several recent works of fiction that leverage the narrative power of the sport: the colorful archetypes and illusions of professional wrestling or the elemental combat of “real” wrestling. Like my repertoire of wrestling moves, these stories are supple and varied, featuring an Armenian immigrant learning the ropes of small-time American professional wrestling, a monomaniacal collegiate wrestler determined to win a national title, and an Ottoman strongman whose life is turned into a disconcerting allegory.

1.

Move over baseball. Professional wrestling, per a character in Chris McCormick’s debut novel The Gimmicks, is the “true American pastime.” The reason lies not in the sport’s popularity but in its metaphorical resonance, its audacious commitment to success via flimflammery. Wrestling is doggedly committed to “the gimmick,” a wrestling term for one’s adopted persona: “What was the American Dream if not the ability to trade gimmick after gimmick until you got one over?” says a wrestling impresario in the novel.

This globetrotting novel, however, is far from an American tale. “Armenian stories require explaining,” we read in the first chapter, and in terms of plot, there’s a lot to explain here. The action follows three childhood friends—beautiful Mina, slight Ruben, and gigantic Avo—in a story that careens around the world from Soviet Armenia to a backgammon tournament in Chantilly, France, to small-town American dives. Mina and Ruben excel at backgammon, while Avo practices a less strategic though no less symbolically weighty sport: wrestling. When Ruben’s violent political activism forces him into exile, he invites Avo to leave behind Mina, now his fiancée, and join him and a radical underground political group in America. Once there, he gains some renown as a professional wrestler called The Brow Beater (aka King Kong of the Caucasus) before disappearing on the eve of a match in Greensboro, N.C.

Certain sections of the novel are narrated by one Terry “Angel Hair” Krill, a cat breeder and former pro wrestler-turned manager who spots Avo at a Los Angeles bar called The Gutshot in the late 1970s. Blessing his “numinous fortune” for encountering the giant Armenian, whose “shoulders had established themselves like kingly epaulettes on either side of his neck,” Krill initiates Avo into the confraternity of knights errant: “As contractors, we were freelancers in almost the medieval sense of the word, fighters and jesters for hire.” Indeed, McCormick depicts the band of hard-living misfits touring the country as beefy Philip Marlowes, strictly adhering to a set of values despite their dissolute lifestyles. For one, they swear by kayfabe, or the oath to protect “the illusion of pro wrestling’s reality.” Moreover, they treat each other with courtly solicitude, “real care”: the spectacle of violence conceals the pains taken not to hurt each other with, say, an overzealous piledriver: “From a distance you see violence. Up close you find love.”

(Hulk Hogan’s commentary about his WrestleMania III match with Andre the Giant, barely able to move because of a bad back, reinforces this view There is indeed something loving about the way the Hulk waits for the ailing giant’s consent before agreeing to bodyslam him. Or consider John Irving, the bard of “real” wrestling, discussing the “civilized aspects to the sport’s combativeness”: “I’ve always admired the rule that holds you responsible, if you lift your opponent off the mat, for your opponent’s safe return.”)

Professional wrestling appeals as a physical form of storytelling, a pulp fiction built on broadly recognizable types, Grand Guignol villains, predictable last-minute reversals of fortune and ingrained cheating: ringside managers interfering in the action and combatants taking advantage of incompetent, distracted, or unconscious referees. These elements give rise to inexhaustible narrative permutations: “It’s wrestling, big fella. We’re only limited by our creativity and how much we’re willing to work,” explains Krill. It is also—and this is important for a novel built around the question of personal and political commitments—a moral form. “We’re in the business of delaying and delivering maximum justice, for maximum effect,” says Krill to his ingenue. The same could be said of the terrorist organization, the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia, that ensnares Avo. “Do you care about justice?” asks its shadowy leader upon first meeting him.

Wrestling does heavy thematic lifting in the book, even if the novel spends more time theorizing rather than dramatizing the spectacle. In wrestling, says Krill, “an elaborate fiction is staged as honest competition,” and the thematic battle between fiction and truth spills out of the ring into every aspect of the novel. Before becoming a semi-professional wrestler, Avo works in a Los Angeles factory making counterfeit silk; before leaving for the States, he proposes to Mina with a cubic zirconium ring (that is, a fake diamond); weary wrestlers mistake flings with groupies, “nights of flesh and mercy,” for true love; a medieval manuscript on backgammon strategy that Mina hopes to sell might not be as old as purported; there are true revolutionaries and those who, if not faking it, are not committed to its violent means; and finally, the Turkish denial of the Armenian genocide entails a grander, more sinister illustration of alternative historical truths.

This synthetic contagion implies that professional wrestling is, by virtue of transparent illusions, the most honest thing in the world. “Call it predetermined,” pleads Krill. “Call it entertainment.” But not [fake].”

2.

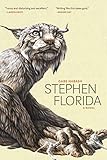

From the wide-ranging The Gimmicks to Gabe Habash’s concentrated debut novel, Stephen Florida, we move from the ring to the mat, as the subject is collegiate, that is, “real” wrestling, and its titular character, a college senior wrestler marked by a “foolish greedy dodo single-mindedness.” (Full disclosure: Habash was formerly my editor at Publishers Weekly.) Over the course of his final year on a rural North Dakota campus, Stephen pursues his goal to win a D4 national championship with a monkish devotion comprising endless repetitions, a Spartan diet, and in-season celibacy.

If in McCormick’s novel the wrestlers cast on and off identities and costumes until they find le gimmick juste, Stephen is a thoroughly engraved character: “I am so much myself, I could never be anyone else.” His body “was preordained to weigh 133 pounds,” the weight class in which he competes, and he willingly submits that body to the trials, and perhaps martyrdom, for which it was destined:

I’m on a one-lane road in a thick metaphorical forest with no distractions. Everything I do is intentional. To arrive at the end of the road is to know Glory in the biblical sense, to put your paternity in Glory. I put my paternity on things. I haven’t studied much on the saints, but it sounds exactly like what their lives were like.

Perhaps, though it is hard to picture St. Francis attempting to put an incensed goat in a cradle hold, as Stephen does in one muddy scene in which he takes on an opponent as stubborn and ready for a fight as he is.

Stephen is the perfect expression of concentrated energy and, because of that concentration, a cipher. He craves competition precisely because “it’s a way to disprove my lack of selfness.” Or as he puts it a little grandiloquently after a victory: “There is no Stephen Florida. I am only a giant collection of gas and light and will.” (In fact, there is literally no Stephen Florida—as he assumes that name only after his coach misspells his real one, Forster, in a recruitment letter.) Wrestling grounds his simultaneously fixed and inchoate character, directs his gaseous will. “I like to spot problems and try to figure them out, which is all wrestling really is,” he says. He does this very effectively with his opponents, but he also has “problems” of a metaphysical sort, especially after suffering a potentially season-ending knee injury. During extended time off, athletes tend to turn their thoughts to Cartesian matters. If Stephen is a wrestler through and through, and that character is tied to a body, then what happens when that body falters?

…is the link so weak that wrestling ends with the body? Does the entire feeling end just like that? The center inside me, encoded with tilts and cradles, could go up in smoke at any moment without a body willing to do its dirty work.

The work is certainly dirty. Philosophy aside, Stephen Florida is a profoundly physical book: blooming cauliflower ears, oozing pus, ripped tendons, smashed noses. Working on his prone opponent, Stephen pushes “his far shoulder like I’m crowbarring open Tut’s tomb.” He is not above gaining an advantage through unsportsmanlike behavior—biting an opponent’s hair or giving him “the old five-on-two,” that is, the surreptitious grabbing of an opponent’s testicles. (Here Stephen is in good, nay angelic company: the first cheap shot in wrestling history is in Genesis, when Jacob’s opponent “touched the hollow of his thigh” in an attempt to break their hours-long standstill.)

And yet, as with all thoughtful sports writing, there is always a sense that there is another, often indescribable plane of action. After one detailed description of the sequence of quicksilver moves leading to an escape, Stephen clarifies that

…none of this looks like how I’m explaining it, trust me, it’s little shivering steps fitted together like violence, which is so abstract as to be the desperate past, an ambulance full of context-free furniture pieces.

And when he’s in the groove, Stephen attains a kind of beatific quietude, the still point of the turning world. Placing his ear on an opponent’s back at the start of a period, he hears the doomed wrestler’s heartbeat: “I could fall asleep here if I stayed long enough.”

Being suspended in a Lotus Eater’s blissful trance of dreamy combat would suit Stephen just fine, but the match, and his college career, must end. The novel is a kind of Bildungsroman in which the hero, almost pathologically sure of his vocation, slowly wakes up to an expanded, and confusing, world outside the confines of the mat.

3.

Ayşe Papatya Bucak’s recent collection The Trojan War Museum contains unsettling, multilayered, and suggestive postmodern tales in which history, storytelling, and violence intertwine. The title story, for example, fancifully chronicles curation gone run amok in an effort to commemorate a foundational battle between cultures. In “A Cautionary Tale,” she presses on this theme, exploring a literal and figurative clash of civilizations in the story of a famed 19th-century Ottoman wrestler. (Tania James also has a wonderful story in her collection Aerogrammes that similarly uses wrestling as a metaphor for imperial attitudes and the misreading of cultures.)

There are few identifying details in the story, but the narrator of “A Cautionary Tale” is an unnamed immigration officer, presumably Turkish, considering the paperwork of an unnamed citizen applying to leave the country. Rather than asking the “proper questions” in such circumstances, the agent tells a fable-like historical story about Yusuf Ismail, “the first of a line of legendary, savage, monstrously large wrestlers all called, one after the other, the Terrible Turk.” Every so often, the agent breaks off the tale to ask the applicant about their reaction to the tale or to establish the hermeneutical mystery confronting both applicant and reader: “I tell everybody these stories. I’m telling you everything for a reason.”

After gaining fame in his Ottoman homeland, Yusuf travels abroad, demolishing European and American opponents. Outlandish tales of his strength and dedication abound: “It’s said he promised to cut his own throat if he was ever beaten,” and so on. In the West, he is portrayed in the press as a noble savage, a brute with a “sluggish Oriental brain” whose physicality is as impressive as it is ungovernable. Abroad, he can communicate with the crowd and the referees solely through pantomime.

Returning home from two fiasco-like, possibly fixed bouts in Madison Square Garden with an American opponent, his ship sinks. The story goes that laden with the 40 pounds of gold he liked to wear around his waist, he frantically tried to pull himself onto an already overloaded life raft. In one version, a sailor, cuts off Yusuf’s grasping hands—silencing the pantomiming Turk in more ways than one.

Apart from the Terrible Turk’s Western tour and gruesome end we also hear the agent describe Yusuf’s halcyon days as a young wrestler, establishing his reputation at a multi-day, open-air tournament at Kirkpinar, the old summer hunting grounds of the sultan. Here amid festive drinking and dancing, hundreds of oiled-up combatants compete for the Ottoman crown in a kind of wrestling Burning Man festival. The camaraderie and honor stand in stark contrast to the sullied matches and ostracism he faces abroad.

The tale completed, the vital questions is posed: “Do you think, in choosing to immigrate, the Turk made a mistake?” The applicant is rightly bemused and bothered by the agent’s bizarre, Socratic line of questioning, which given the role of gatekeeper takes on an authoritarian tenor: “This isn’t right. It’s not for you to decide,” the applicant says at one point.” Is the agent a petty tyrant with a stamp or a kindly dispenser of prophetic wisdom about the perils of xenophobia?

A question to wrestle with.

Bonus Links from Our Archive:

— A Year in Reading: Gabe Habash

— Two Writers, One Marriage: The Millions Interviews Julie Buntin and Gabe Habash

— A Year in Reading: Chris McCormick

— A Year in Reading: Ayşe Papatya Bucak

— ‘The Trojan War Museum’: Featured Fiction from Ayse Papatya Bucak

— A Year in Reading: Tania James

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.