Here are six notable books of poetry publishing this month.

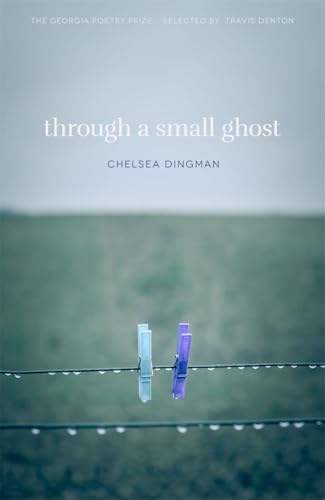

Through a Small Ghost by Chelsea Dingman

“I wanted to give you the world.” The narrator of “Memento Mori,” the first poem in Dingman’s new book, speaks those words to the child inside of her. And yet she knows “my body is / the house you will ever forget how to breathe in.” Dingman has the gift to see the world through a wound. In “Intersections,” the narrator encounters a mare “alone in a field, her belly / distended, ribs like ladder rungs.” The occasional wind rustles oak trees, and the mare “spits & shakes” as well. “I’ve seen this before,” the narrator says: “the way a woman’s body reaches // for its own ruin.” There’s wind elsewhere in this book, and its spirit and haunt is the perfect metaphor (I think of John 3:8–“The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth.”). In “Postscript,” she writes: “A wind chime on my mother’s porch. / The prairies. The constant wind / tears through me like a new language. / Like it’s whispering empty empty empty.” These poems are hymns to a lost daughter. An affirmation. “How briefly the body is a story / where everything matters, // even its name.” And: “When the world // shows us that it’s incapable / of mercy, we stay up all night / & practice how to be merciful.” One of the best books this year.

Romances by Lisa Ampleman

The first two poems of Ampleman’s new collection follow Andreas Capellanus, a likely pseudonym for the author of a 12th century satirical volume on courtly love. Ampleman immediately brings him to the present day with her own form of humor–a little whimsical, a little absurd, always clever (Rule #2: “Unrequited love is like insulation–toxic / cotton candy hidden beneath gypsum board. / It will keep you warm all winter.”). But Ampleman turns in her own direction to create a farcical take on contemporary love, yet one stitched with real sentiment. In “Love-Scrawls,” the narrator thinks about how we “carve trees, scrape the bark to make our confession, / our affinities simplified to initials / in a lopsided heart.” Not to mention the affirmations on bathroom stalls and biceps. We know that “flesh stretches, ink fades,” but love is not logical. Love is unpredictable, of course (this could be the only book to include a sonnet sequence dedicated to Courtney Love–“I transcribe and mimeograph you for the sake / of those who’ve loved and lost, or sighed / over a sonnet.”). Ampleman is the perfect guide for this subject.

The first two poems of Ampleman’s new collection follow Andreas Capellanus, a likely pseudonym for the author of a 12th century satirical volume on courtly love. Ampleman immediately brings him to the present day with her own form of humor–a little whimsical, a little absurd, always clever (Rule #2: “Unrequited love is like insulation–toxic / cotton candy hidden beneath gypsum board. / It will keep you warm all winter.”). But Ampleman turns in her own direction to create a farcical take on contemporary love, yet one stitched with real sentiment. In “Love-Scrawls,” the narrator thinks about how we “carve trees, scrape the bark to make our confession, / our affinities simplified to initials / in a lopsided heart.” Not to mention the affirmations on bathroom stalls and biceps. We know that “flesh stretches, ink fades,” but love is not logical. Love is unpredictable, of course (this could be the only book to include a sonnet sequence dedicated to Courtney Love–“I transcribe and mimeograph you for the sake / of those who’ve loved and lost, or sighed / over a sonnet.”). Ampleman is the perfect guide for this subject.

Living Weapon by Rowan Ricardo Phillips

In his prose introduction to this collection, Phillips writes that “we all make art with the same material–time, art is made of time.” Time–inexorable, constant, unconcerned with us despite our obsession with it–plays a distinct role in his new book. He imagines history as a lover who “promises you a kiss / When she comes to bed.” Until then, she, “like every night this summer, stays up / To watch her shows.” History wakes you not with the light of dawn, but “just the white haze of her cell. / You stayed half-awake in the lit darkness / Thinking she owed you something.” Maybe a kiss, maybe more, but then the “light turned off as if it never happened. / And nothing came to you because you were / Owed absolutely nothing.” There’s a touch of Stevens here, of Warren. In another poem, “We wander round ring after ring of life, / One after another, blossoms of light / To which we’re but a mere flotsam of bees.” Remember: “Yesterday’s newspapers becomes last week’s / Newspapers spread like a hand-held fan / In front of the face of the apartment / Door.” The truths of Phillips’s book are plain and perceptive, harsh and oddly soothing.

In his prose introduction to this collection, Phillips writes that “we all make art with the same material–time, art is made of time.” Time–inexorable, constant, unconcerned with us despite our obsession with it–plays a distinct role in his new book. He imagines history as a lover who “promises you a kiss / When she comes to bed.” Until then, she, “like every night this summer, stays up / To watch her shows.” History wakes you not with the light of dawn, but “just the white haze of her cell. / You stayed half-awake in the lit darkness / Thinking she owed you something.” Maybe a kiss, maybe more, but then the “light turned off as if it never happened. / And nothing came to you because you were / Owed absolutely nothing.” There’s a touch of Stevens here, of Warren. In another poem, “We wander round ring after ring of life, / One after another, blossoms of light / To which we’re but a mere flotsam of bees.” Remember: “Yesterday’s newspapers becomes last week’s / Newspapers spread like a hand-held fan / In front of the face of the apartment / Door.” The truths of Phillips’s book are plain and perceptive, harsh and oddly soothing.

A Nail the Evening Hangs On by Monica Sok

Sok has an impressive sense of story in this debut collection. In “American Dancing in the Heart of Darkness,” the narrator, of Cambodian heritage, is in Phnom Penh for the Water Festival. She is surrounded by American students, and considers “maybe I’m American too.” She and the other students stay at the Golden Gate Hotel, where she orders room service–“fresh young coconut, a club sandwich, and French fries”–delivered by a “woman with a bruised face and a silver tray” who has to walk seven floors to her room. The woman will make the same trip almost nine times that night to other rooms, American rooms. The next morning, hundreds are killed and injured in a human stampede at Koh Pich, and the narrator hears from her family. The Americans nod in recognition at the horror, but the narrator is no traveler. Confused, and dizzy with grief, she goes “to the Heart of Darkness, the nightclub empty but open. / We dance with Khmer boys.” The calls announcing deaths continue to arrive that night. It’s an early poem in the book, but Sok never lets up, her detailed sense creating almost constant suspense and tension in this collection. A significant new voice.

Sok has an impressive sense of story in this debut collection. In “American Dancing in the Heart of Darkness,” the narrator, of Cambodian heritage, is in Phnom Penh for the Water Festival. She is surrounded by American students, and considers “maybe I’m American too.” She and the other students stay at the Golden Gate Hotel, where she orders room service–“fresh young coconut, a club sandwich, and French fries”–delivered by a “woman with a bruised face and a silver tray” who has to walk seven floors to her room. The woman will make the same trip almost nine times that night to other rooms, American rooms. The next morning, hundreds are killed and injured in a human stampede at Koh Pich, and the narrator hears from her family. The Americans nod in recognition at the horror, but the narrator is no traveler. Confused, and dizzy with grief, she goes “to the Heart of Darkness, the nightclub empty but open. / We dance with Khmer boys.” The calls announcing deaths continue to arrive that night. It’s an early poem in the book, but Sok never lets up, her detailed sense creating almost constant suspense and tension in this collection. A significant new voice.

Praise Song for My Children: New and Selected Poems by Patricia Jabbeh Wesley

These are affirming poems–songs, truly. In the title poem, Wesley writes “Let me come to you at dawn, my children, / my calabash, wet from the early dawn’s / water-fetching run.” Wet, tired, and yet determined: “Let me come to you bearing tears on my face / after the war, after the villages have crumbled / under the weight of grave hate.” The power of Wesley’s collected work here is established in the book’s first poem, “Some of Us Are Made of Steel,” blessedly inspirational verse for a world that needs it: “life has made us cry. / But in our tears, salt, healing, salty, and forever, / we are forever. Yes, some of us are forever.” In one poem, Wesley is thankful for graces common and uncommon, including suffering. Such willingness to see the grace in pain informs the rest of her book, steeped in elegies and remembrances that avoid nihilism. “When I meet my mother,” Wesley writes, “she will take / from my tired hands, this bundle of rotten / leaves and the pail of tears / I have brought to her.” She writes of Liberia and war, and leaving Liberia–but hopefully not forever. “One of these days / there will be rejoicing / all over the place,” she promises. “All of us refugees / will come home again.”

These are affirming poems–songs, truly. In the title poem, Wesley writes “Let me come to you at dawn, my children, / my calabash, wet from the early dawn’s / water-fetching run.” Wet, tired, and yet determined: “Let me come to you bearing tears on my face / after the war, after the villages have crumbled / under the weight of grave hate.” The power of Wesley’s collected work here is established in the book’s first poem, “Some of Us Are Made of Steel,” blessedly inspirational verse for a world that needs it: “life has made us cry. / But in our tears, salt, healing, salty, and forever, / we are forever. Yes, some of us are forever.” In one poem, Wesley is thankful for graces common and uncommon, including suffering. Such willingness to see the grace in pain informs the rest of her book, steeped in elegies and remembrances that avoid nihilism. “When I meet my mother,” Wesley writes, “she will take / from my tired hands, this bundle of rotten / leaves and the pail of tears / I have brought to her.” She writes of Liberia and war, and leaving Liberia–but hopefully not forever. “One of these days / there will be rejoicing / all over the place,” she promises. “All of us refugees / will come home again.”

Still Life by Ciaran Carson

The late Carson’s final volume begins with the word “Today,” and that first line ends with the phrase “here I am”–an appropriate formulation. His long lines, their ends pushing past the margin and running down the center, create a root in the present. Carson speaks often of his terminal diagnosis in these poems: “How strange it is to be lying here listening to whatever it is going on. / The days are getting longer now, however many of them I have left. / And the pencil I am writing this with, old as it is, will easily outlast their end.” There is a bravery in offering oneself over to elegy, although the book never feels maudlin–owing to Carson’s range, his almost ravenous curiosity.

The late Carson’s final volume begins with the word “Today,” and that first line ends with the phrase “here I am”–an appropriate formulation. His long lines, their ends pushing past the margin and running down the center, create a root in the present. Carson speaks often of his terminal diagnosis in these poems: “How strange it is to be lying here listening to whatever it is going on. / The days are getting longer now, however many of them I have left. / And the pencil I am writing this with, old as it is, will easily outlast their end.” There is a bravery in offering oneself over to elegy, although the book never feels maudlin–owing to Carson’s range, his almost ravenous curiosity.