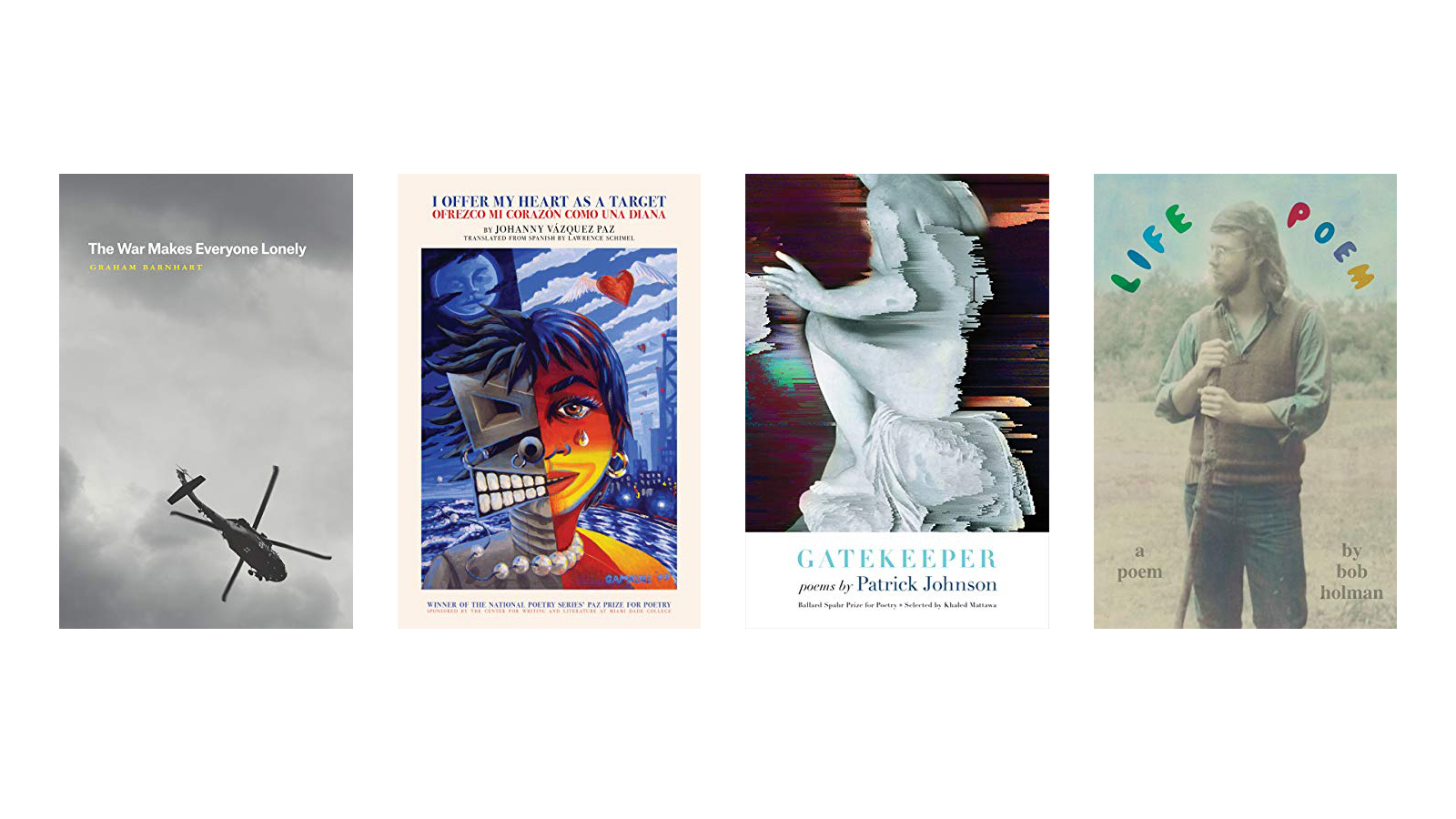

Here are four notable books of poetry publishing this month.

The War Makes Everyone Lonely by Graham Barnhart

“Unlike life, / war can be survived.” Barnhart’s debut is full of these sharp, solemn touches about war and the shadow of military service. A former US Army Special Forces medic in Iraq and Afghanistan, Barnhart’s book shares the spirit of Phil Klay’s story collection Redeployment: testaments to the lasting memories of lives burned by violence. When he ends one poem “the guns were loud–loud like gods applauding,” there’s an acute sense that Barnhart is especially skilled at capturing the encompassing feeling of war. In the excellent titular poem, the narrator says his sister “had been receiving a lot of calls / from strangers” asking for Elisha, since her number was listed on an escort site. Meanwhile, the narrator, deployed in Afghanistan, sits “in a little plywood room painted red, / hung with pictures of the other guys’ wives.” Bored, he repeats twice that “nothing ever happens.” Barnhart, true to his title, is talented at crafting moments of loneliness–both in scene and in line (one poem, “Survival and Evasion,” is sapped of moisture, so that its lines feel soured and clipped, the perfect tone: “Day nine: turned our tongues to chalk / with unripe persimmons. Used them to bait / a snare instead.”). One of the most important debuts this year.

“Unlike life, / war can be survived.” Barnhart’s debut is full of these sharp, solemn touches about war and the shadow of military service. A former US Army Special Forces medic in Iraq and Afghanistan, Barnhart’s book shares the spirit of Phil Klay’s story collection Redeployment: testaments to the lasting memories of lives burned by violence. When he ends one poem “the guns were loud–loud like gods applauding,” there’s an acute sense that Barnhart is especially skilled at capturing the encompassing feeling of war. In the excellent titular poem, the narrator says his sister “had been receiving a lot of calls / from strangers” asking for Elisha, since her number was listed on an escort site. Meanwhile, the narrator, deployed in Afghanistan, sits “in a little plywood room painted red, / hung with pictures of the other guys’ wives.” Bored, he repeats twice that “nothing ever happens.” Barnhart, true to his title, is talented at crafting moments of loneliness–both in scene and in line (one poem, “Survival and Evasion,” is sapped of moisture, so that its lines feel soured and clipped, the perfect tone: “Day nine: turned our tongues to chalk / with unripe persimmons. Used them to bait / a snare instead.”). One of the most important debuts this year.

I Offer My Heart as a Target (Ofrezco Mi Corazón Como Una Diana) by Johanny Vázquez Paz (translated by Lawrence Schimel)

“Love my scar / discover in its ugliness the perfect geography / where tears find their bearings with laughter.” Paz compels us to look closer, and longer, at bodies worn, stressed, and hurt. Often her narrators are hurt by men–in the shadows and under the light, in the past and in the present. “And they say that I let them,” one narrator laments, “by not squealing madly / shouting my panic / to my friends / saving my family / from the shame.” Paz creates a sense of shared shame; after all, her narrators have inherited so much from their family: “I don’t know at what moment / my sisters inhabited me, / when they looted my room / to install their own belongings / and furnish me with their dreams.” She ends the poem: “I am a hundred women in one / hybrid of virgin possibilities / and I feel on my skin the pain and the laughter / of all the warrior women I inherited.” Paz’s book is full of tradition, tension, and rage: “Without strength to fulfill the vengeances / I wreak every night in my sleep / when I dream that I am another woman / who doesn’t awaken in me.”

“Love my scar / discover in its ugliness the perfect geography / where tears find their bearings with laughter.” Paz compels us to look closer, and longer, at bodies worn, stressed, and hurt. Often her narrators are hurt by men–in the shadows and under the light, in the past and in the present. “And they say that I let them,” one narrator laments, “by not squealing madly / shouting my panic / to my friends / saving my family / from the shame.” Paz creates a sense of shared shame; after all, her narrators have inherited so much from their family: “I don’t know at what moment / my sisters inhabited me, / when they looted my room / to install their own belongings / and furnish me with their dreams.” She ends the poem: “I am a hundred women in one / hybrid of virgin possibilities / and I feel on my skin the pain and the laughter / of all the warrior women I inherited.” Paz’s book is full of tradition, tension, and rage: “Without strength to fulfill the vengeances / I wreak every night in my sleep / when I dream that I am another woman / who doesn’t awaken in me.”

Gatekeeper by Patrick Johnson

Fragmented and fractured, Johnson pushes this book to its structural limits–and the result is a successfully jarring and disturbing collection. This is a book of the internet, and of our internal selves: of pursuit, lust, and a closing into the spirit. Prose-poetic pages offer intermittent, dramatic scenes that create a narrative through-line for the book: the narrator, curiosity piqued by the possibilities of the hidden and deep web, begins searching and stalking that space. Johnson’s vision here is a world that we all dabble in–at the least the surface of it, on which these very words are being read–but Johnson pushes us lower, invites us in, and wonders what would help when we follow this medium to its logical (or illogical) conclusion. “We talk for months without exchanging names,” the narrator says of his relationships with Anon, a phantom voice, a source of distant intrigue. Johnson takes on a breakneck feel in the book, and when he steps out from the online space, as in poems like “black mirror (slowly),” the dystopia remains. Even though the narrator takes a break from the computer, he longs for a return: “This desire, an impulse, undoes me.” Is this digital love? Gatekeeper offers uncomfortable possibilities.

Fragmented and fractured, Johnson pushes this book to its structural limits–and the result is a successfully jarring and disturbing collection. This is a book of the internet, and of our internal selves: of pursuit, lust, and a closing into the spirit. Prose-poetic pages offer intermittent, dramatic scenes that create a narrative through-line for the book: the narrator, curiosity piqued by the possibilities of the hidden and deep web, begins searching and stalking that space. Johnson’s vision here is a world that we all dabble in–at the least the surface of it, on which these very words are being read–but Johnson pushes us lower, invites us in, and wonders what would help when we follow this medium to its logical (or illogical) conclusion. “We talk for months without exchanging names,” the narrator says of his relationships with Anon, a phantom voice, a source of distant intrigue. Johnson takes on a breakneck feel in the book, and when he steps out from the online space, as in poems like “black mirror (slowly),” the dystopia remains. Even though the narrator takes a break from the computer, he longs for a return: “This desire, an impulse, undoes me.” Is this digital love? Gatekeeper offers uncomfortable possibilities.

Life Poem by Bob Holman

Holman wrote Life Poem in 1969, when he was 21. There’s been a lifetime between that manuscript and now–a lifetime during which Holman has been an activist, poet, professor, promoter of poetry, and more. When Holman cites the Jesuit critic Walter Ong, S.J. in his foreword (“life fits into poem the way that meaning is nested in sound”), it feels like we are entering into a pleasant and quirky time capsule, and Life Poem delivers in the book proper. “desperate now, i’ve started to write everything that comes into my head” the narrator begins, and he does collect varied streams and rivers of consciousness in looping lines. “what if i laughed louder? / could you believe me then?” the narrator asks, his lines frenzied but never inane, delivered with dizzying wordplay (“university students of the world, ignite!”). Other sections are deceptively, powerfully solemn: “we’ve begun pulling men out of Viet Nam! / hooray! we shout, yea, the boys are coming home! / only they aren’t coming home–they’re being sent to the Middle East / wars should be fought under supervision of mothers / and all the boys must be home by eleven.”

Holman wrote Life Poem in 1969, when he was 21. There’s been a lifetime between that manuscript and now–a lifetime during which Holman has been an activist, poet, professor, promoter of poetry, and more. When Holman cites the Jesuit critic Walter Ong, S.J. in his foreword (“life fits into poem the way that meaning is nested in sound”), it feels like we are entering into a pleasant and quirky time capsule, and Life Poem delivers in the book proper. “desperate now, i’ve started to write everything that comes into my head” the narrator begins, and he does collect varied streams and rivers of consciousness in looping lines. “what if i laughed louder? / could you believe me then?” the narrator asks, his lines frenzied but never inane, delivered with dizzying wordplay (“university students of the world, ignite!”). Other sections are deceptively, powerfully solemn: “we’ve begun pulling men out of Viet Nam! / hooray! we shout, yea, the boys are coming home! / only they aren’t coming home–they’re being sent to the Middle East / wars should be fought under supervision of mothers / and all the boys must be home by eleven.”