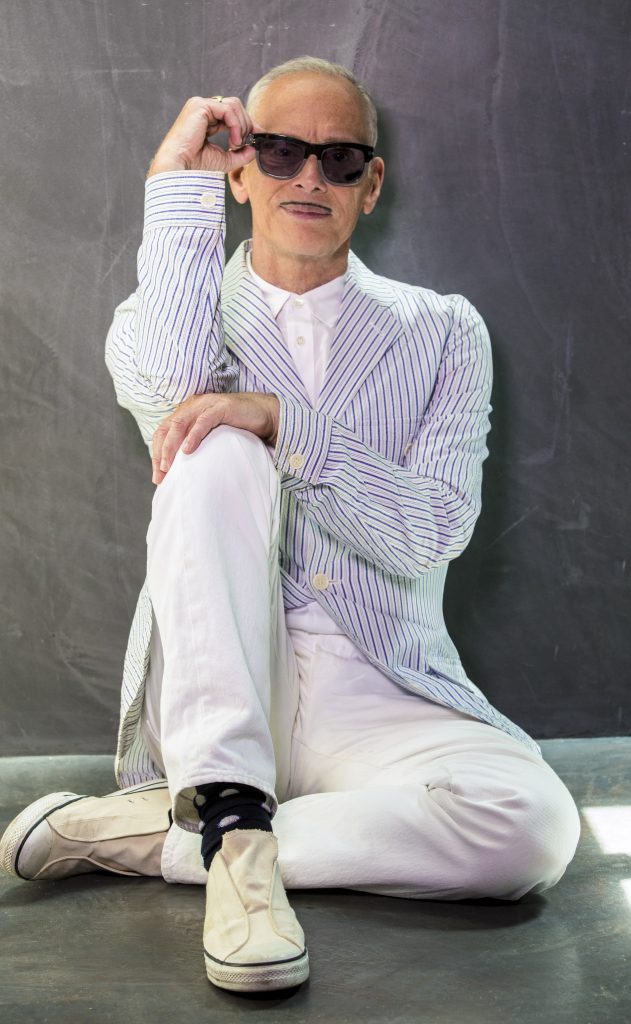

Back in Baltimore after the third annual John Waters Camp, where fans live and dress like his characters over a long weekend, the transgressive filmmaker was still processing his new status of respectability. “A lot of people said, ‘My parents told me about your movies,’” he says. “When I was young, their parents called the police when they found them with my movies. So a lot has changed.” His newest book, Mr. Know-It-All, tracks the Prince of Puke’s evolution into insider and offers advice—like harnessing one’s insanity and finding happiness through creative fulfillment—for the misfits and weirdos plagued by crazy ideas.

Back in Baltimore after the third annual John Waters Camp, where fans live and dress like his characters over a long weekend, the transgressive filmmaker was still processing his new status of respectability. “A lot of people said, ‘My parents told me about your movies,’” he says. “When I was young, their parents called the police when they found them with my movies. So a lot has changed.” His newest book, Mr. Know-It-All, tracks the Prince of Puke’s evolution into insider and offers advice—like harnessing one’s insanity and finding happiness through creative fulfillment—for the misfits and weirdos plagued by crazy ideas.

“I’m being Norman Vincent Peale for the neurotics,” he says, “although I actually don’t think my fans are neurotic. I think when society told them they were crazy, they learned how to triumph above that. Mr. Know-It-All is like all self-help books, but at the same time I might be telling you to go a very different way than you’ve been taught by your parents or what came before.”

Waters, who wrote all of his dozen feature films, published his first book, Shock Value, in 1981. The memoir covered the making of classic midnight movies, like Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble, and chronicled his childhood in Baltimore, the “hairdo capital of the world,” a line that anticipated his best-known work, Hairspray, which features a “hairbopper” played by Rikki Lake who championed body positivity before it was a thing. His next film, Cry-Baby, spoofed Elvis movies and their fans. While straight men from his generation like Bruce Springsteen cite Elvis as the inspiration to pick up a guitar, Waters writes that it was Elvis who made him realize he was gay. “Is there anything more rock ’n’ roll than whacking off the first time to Elvis Presley?”

Waters, who wrote all of his dozen feature films, published his first book, Shock Value, in 1981. The memoir covered the making of classic midnight movies, like Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble, and chronicled his childhood in Baltimore, the “hairdo capital of the world,” a line that anticipated his best-known work, Hairspray, which features a “hairbopper” played by Rikki Lake who championed body positivity before it was a thing. His next film, Cry-Baby, spoofed Elvis movies and their fans. While straight men from his generation like Bruce Springsteen cite Elvis as the inspiration to pick up a guitar, Waters writes that it was Elvis who made him realize he was gay. “Is there anything more rock ’n’ roll than whacking off the first time to Elvis Presley?”

Asked when he started writing, he says, “That’s what I really am, more than anything, a writer. That’s how I could discover forbidden worlds. Life magazine corrupted me because I read about beatniks and Tennessee Williams and drug addicts and homosexuals and everything.” He also learned at an early age that his delight in grotesque material could be contagious—and dangerous. As a 12-year-old at summer camp he wrote a horror story called “Reunion.” “I read it each night around the campfire,” he says. “At the end, there was this hideous gore and people had nightmares. The parents called the camp and called my parents and complained, so right from the beginning it was trouble.” Later, his first published work, “Inside an Unwed Mother’s Home,” written under the pseudonym Jane Wiemo, proved to be an exercise in drag. “It was written for Fact magazine,” he says, “but I made it up!”

Other books include Crackpot, a collection of journalism published in Rolling Stone, and Carsick, which is built around the stunt of hitchhiking across the country. Waters is no stranger to stunts—at screenings for Polyester, audience members received scratch-and-sniff Odorama cards with smells that corresponded to scenes from the film. In Mr. Know-It-All, he explains how the idea emerged from an unsympathetic critic’s warning to readers: “If you ever see Waters’s name on the marquee, walk on the other side of the street and hold your nose.” His response? Fill up scratch-and-sniff cards with smells of flatulence, gasoline, and skunk spray. Somehow, Waters knew that proving his critics right was always the best way to build an audience. He also needed a new business plan after the decline of midnight movie theaters. “People wanted to see [movies] at any time, at their house, with their friends, and smoke their pot that they didn’t have to hide from nosy ushers,” he writes in Mr. Know-It-All. “Better yet, they could jerk off while watching—the real reason home videos became so big.”

Other books include Crackpot, a collection of journalism published in Rolling Stone, and Carsick, which is built around the stunt of hitchhiking across the country. Waters is no stranger to stunts—at screenings for Polyester, audience members received scratch-and-sniff Odorama cards with smells that corresponded to scenes from the film. In Mr. Know-It-All, he explains how the idea emerged from an unsympathetic critic’s warning to readers: “If you ever see Waters’s name on the marquee, walk on the other side of the street and hold your nose.” His response? Fill up scratch-and-sniff cards with smells of flatulence, gasoline, and skunk spray. Somehow, Waters knew that proving his critics right was always the best way to build an audience. He also needed a new business plan after the decline of midnight movie theaters. “People wanted to see [movies] at any time, at their house, with their friends, and smoke their pot that they didn’t have to hide from nosy ushers,” he writes in Mr. Know-It-All. “Better yet, they could jerk off while watching—the real reason home videos became so big.”

When I tell him that I was 13 the first time I saw a John Waters movie on VHS, he says, “God, that might’ve been illegal.” Then I name the film—Serial Mom—and he claimed it’s his best. In the book, he describes the original pitch: “Not the usual John Waters movie about crazy people in a crazy world, but a movie about a normal person in a realistic world doing the craziest thing of all as the audience cheers her on!” Kathleen Turner played the titular homicidal maniac straight, and a suburban rampage became punk rock catharsis, complete with a scene starring the band L7 scorching a Baltimore club as Camel Lips.

With right-wing provocateurs co-opting the absurd theatrics of the radical leftists who inspired him in the 1970s, Waters hasn’t given up the urge to provoke. In a chapter on the sex clubs of yesteryear, he pitches a business plan: a club for gay people to copulate with the opposite sex and create, he says, a “new sexual minority… Gay heterosexuality.” The name of the club? Flip Flop.

“They flipped out when [I proposed this at the John Waters Camp],” he says. “But they laughed, that’s the whole thing. The main thing I’m trying to do is make you laugh. If I’m taking you into a world that makes you uncomfortable, people are okay if I’m the guide, because I’m not mean. I’m mean about the Catholic Church, but that’s not mean, that’s protection. That’s religious war.”

It’s been 15 years since Waters has released a film, though he’s not bitter toward Hollywood. “I have been paid to write many movies since A Dirty Shame,” he says. “As I said in the book, I don’t really complain about anything, but I do believe that I’ve probably made my last movie. I think I’m just in the wrong business because my movies have shelf lives, like what you want with a book. It’s always in print and always there’s two copies in every bookstore, even 40 years later.”

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly and the Miami Book Fair.

Lead image credit: Larry Dean