Here are five notable books of poetry publishing in October.

Railsplitter by Maurice Manning

Manning’s collection of poems written through the persona of our sixteenth president begins, appropriately enough, with an exercise in persona from the man himself. Dated July 19, 1863, Lincoln’s short satire channels the voice of General Lee: “The Yankees they got arter us, and / giv us particular hell.” While the piece isn’t his best work (he wrote a fair number of poems), it is appropriate for Manning’s difficult project: how to write new and arresting work in such an established voice? The key, perhaps, comes from Manning’s perception of poetry as rooted in theatrics: he imagines writing poems “that could be performed on a stage with a set.” That mixture of oration, space, and the certain surrealism of theater matches well with Railsplitter. In “Transcendentalism,” he starts: “One of the things the actor’s bullet failed / to do was to interrupt the rhythm // of thought, the flow of the mind as it moves around.” Witty, whimsical, and imbued with the strangeness of the afterlife, Manning’s Lincoln is an endearing, complex narrator. A favorite among favorites is “The Smell of Open Ground in Spring.” Unmarked family graves surround the narrator. Those dead, like so many “innumerable / existences” who “have come and gone and gone / to dust.” He thinks of his mother’s death, and thinks of the power of poetry. He concludes: “While irony may wrap itself around / a poem, the true poem in the end / escapes the shroud. It’s the art of resurrection.”

Manning’s collection of poems written through the persona of our sixteenth president begins, appropriately enough, with an exercise in persona from the man himself. Dated July 19, 1863, Lincoln’s short satire channels the voice of General Lee: “The Yankees they got arter us, and / giv us particular hell.” While the piece isn’t his best work (he wrote a fair number of poems), it is appropriate for Manning’s difficult project: how to write new and arresting work in such an established voice? The key, perhaps, comes from Manning’s perception of poetry as rooted in theatrics: he imagines writing poems “that could be performed on a stage with a set.” That mixture of oration, space, and the certain surrealism of theater matches well with Railsplitter. In “Transcendentalism,” he starts: “One of the things the actor’s bullet failed / to do was to interrupt the rhythm // of thought, the flow of the mind as it moves around.” Witty, whimsical, and imbued with the strangeness of the afterlife, Manning’s Lincoln is an endearing, complex narrator. A favorite among favorites is “The Smell of Open Ground in Spring.” Unmarked family graves surround the narrator. Those dead, like so many “innumerable / existences” who “have come and gone and gone / to dust.” He thinks of his mother’s death, and thinks of the power of poetry. He concludes: “While irony may wrap itself around / a poem, the true poem in the end / escapes the shroud. It’s the art of resurrection.”

Space Struck by Paige Lewis

One of the best debuts of the year. Poem by poem, Lewis builds a menagerie of mood and matter. In “No One Cares Until You’re the Last of Something,” “a line of binoculared men” have come to the narrator’s house bearing “buckets of mealworms.” An ivory-billed woodpecker on the narrator’s back porch has captivated these anxious souls. Decked in “splendid hiking shorts,” the bird-watchers “press their noses against my sliding glass door” and seek entry. At night, the narrator turns off the lights, but soon the visitors make a nest of the home: “They remove their shoes and lie down on countertops, / in closets, and underneath my staircase. Wherever / there’s space, they fill it—body against tired body— / pressed close as feathers.” A Lewis poem can go anywhere. “Saccadic Masking” is visceral, internal. “When They Find the Ark” is clever. “The Terre Haute Planetarium Rejected My Proposal” is hilarious. “God Stops By” is curious—a trademark Lewis piece. There, God offers the narrator fat from his steak, but the narrator passes: “it’s hard to feel hungry / when everything in this world tastes small // and wrong, like rubber grapes or sun-boiled / eggs.” Space Struck demonstrates range, delivered in comedic lines that reveal a unique humor. “Build me a house with so many rooms,” one poem begins—an apt metaphor to capture Lewis’s approach.

One of the best debuts of the year. Poem by poem, Lewis builds a menagerie of mood and matter. In “No One Cares Until You’re the Last of Something,” “a line of binoculared men” have come to the narrator’s house bearing “buckets of mealworms.” An ivory-billed woodpecker on the narrator’s back porch has captivated these anxious souls. Decked in “splendid hiking shorts,” the bird-watchers “press their noses against my sliding glass door” and seek entry. At night, the narrator turns off the lights, but soon the visitors make a nest of the home: “They remove their shoes and lie down on countertops, / in closets, and underneath my staircase. Wherever / there’s space, they fill it—body against tired body— / pressed close as feathers.” A Lewis poem can go anywhere. “Saccadic Masking” is visceral, internal. “When They Find the Ark” is clever. “The Terre Haute Planetarium Rejected My Proposal” is hilarious. “God Stops By” is curious—a trademark Lewis piece. There, God offers the narrator fat from his steak, but the narrator passes: “it’s hard to feel hungry / when everything in this world tastes small // and wrong, like rubber grapes or sun-boiled / eggs.” Space Struck demonstrates range, delivered in comedic lines that reveal a unique humor. “Build me a house with so many rooms,” one poem begins—an apt metaphor to capture Lewis’s approach.

Nervous System by Rosalie Moffett

“I’m seeking to understand my mother’s brain and life post severe concussion,” Moffett has said of the long, titular poem in her new book, “and also grappling in a larger way with my fears and horror of having a mother, who, like all mothers, is mortal. Often, I’m casting around for a way look in—to the body, to the brain, to the ‘beyond’—but can only do it by trafficking in the seen world, in the world we all share.” Nervous System builds with sometimes bold, sometimes weary stretches toward that lost sense of understanding that comes from an injured brain. A “bright midday” head injury causes a concussion: “a shell, cool well / of clues.” Her bed-ridden mother “relearned the names / for things—flood, daughter, glove—lights // flickering on in her planetarium.” We grasp for metaphor when we need representation, and Moffett lunges and leaps there: “I’ve drawn a lot of pictures / because it’s hard for me to believe // in anything / that hasn’t been made / into something else.” Nervous System works so well because, in addition to her relational language, the long poem is steeped in flashback detail, and the inextricable link between mother and daughter: “I am gentle, patient, easy to awe. This goodness I got // from her is bound / to be yoked to a curse—no bargain / is so good.”

“I’m seeking to understand my mother’s brain and life post severe concussion,” Moffett has said of the long, titular poem in her new book, “and also grappling in a larger way with my fears and horror of having a mother, who, like all mothers, is mortal. Often, I’m casting around for a way look in—to the body, to the brain, to the ‘beyond’—but can only do it by trafficking in the seen world, in the world we all share.” Nervous System builds with sometimes bold, sometimes weary stretches toward that lost sense of understanding that comes from an injured brain. A “bright midday” head injury causes a concussion: “a shell, cool well / of clues.” Her bed-ridden mother “relearned the names / for things—flood, daughter, glove—lights // flickering on in her planetarium.” We grasp for metaphor when we need representation, and Moffett lunges and leaps there: “I’ve drawn a lot of pictures / because it’s hard for me to believe // in anything / that hasn’t been made / into something else.” Nervous System works so well because, in addition to her relational language, the long poem is steeped in flashback detail, and the inextricable link between mother and daughter: “I am gentle, patient, easy to awe. This goodness I got // from her is bound / to be yoked to a curse—no bargain / is so good.”

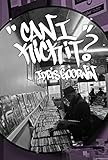

Can I Kick It? by Idris Goodwin

“Black art is inherently about disruption—that’s what jazz is, that’s what hip-hop is,” Goodwin once told American Theatre. Goodwin was talking specifically about his plays, but that sense of disruption is central to his new book of poems. Mixes and revisions abound here. In the collection’s first poem, “Back to the Afro-Future, 1965,” the narrator messes with stereo equipment and old record players to “blend the Temptations into the Tops.” Soon he is lost in the moment and its meaning: “I start cutting it up / crab, transform / scratch, blend”—his lines moving from sentences to phrases, a fissure in the poem and memory. “Break Down,” a poem in response to Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring’s admitted 80s-era blackface, follows those faultlines of both culture and language: “Rap make you wanna be another man / You Black your face, Black your face // It’s not racist, you’re such a fan.” “Of the Lord” is a poem invoked to classic skywalker Dominique Wilkins: “We like our names with / Peaks, slopes, and vowels // We like our names to be aerial / and aural, throat and teeth and tongue / Our names gotta be songs.”

“Black art is inherently about disruption—that’s what jazz is, that’s what hip-hop is,” Goodwin once told American Theatre. Goodwin was talking specifically about his plays, but that sense of disruption is central to his new book of poems. Mixes and revisions abound here. In the collection’s first poem, “Back to the Afro-Future, 1965,” the narrator messes with stereo equipment and old record players to “blend the Temptations into the Tops.” Soon he is lost in the moment and its meaning: “I start cutting it up / crab, transform / scratch, blend”—his lines moving from sentences to phrases, a fissure in the poem and memory. “Break Down,” a poem in response to Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring’s admitted 80s-era blackface, follows those faultlines of both culture and language: “Rap make you wanna be another man / You Black your face, Black your face // It’s not racist, you’re such a fan.” “Of the Lord” is a poem invoked to classic skywalker Dominique Wilkins: “We like our names with / Peaks, slopes, and vowels // We like our names to be aerial / and aural, throat and teeth and tongue / Our names gotta be songs.”

Bodega by Su Hwang

These poems demand to be sounded-out and savored. “Manholes hiss secrets,” Hwang begins one poem. “Inside: a transistor radio with foil-tipped antennae sputters the Yankees doubleheader.” We are in a Queensbridge bodega owned by Korean immigrants, and the narrative eye and ear is gentle, encompassing, hypnotic. “Gust of wet heat enters with an elderly Nigerian man wearing a beret & wooden cane in the other—his salt-and-pepper hair gathered into a seahorse.” Hwang is adept at capturing action and setting, as well as more intangible touches: “How far do you have to travel to arrive / at dying,” she writes in an elegy for her grandmothers. Some poems swoop across the page, riding sound and form; others, like “Latchkeys,” are pointed narratives contained by closed spaces. In that poem, the narrator is with her brother, waiting for her parents to come home. When their “headlights cast shadow / puppets against the living / room wall,” she and her brother scramble to seem responsible: studying biology, playing the upright Yamaha. Her father would head into the backyard “to hit / a golf ball on a string / while mother silently made / dinner: rice, kimchi, Spam / as we three listened / from different corners / of the house / to a tiny white ball / greeting iron.” A strong debut.

These poems demand to be sounded-out and savored. “Manholes hiss secrets,” Hwang begins one poem. “Inside: a transistor radio with foil-tipped antennae sputters the Yankees doubleheader.” We are in a Queensbridge bodega owned by Korean immigrants, and the narrative eye and ear is gentle, encompassing, hypnotic. “Gust of wet heat enters with an elderly Nigerian man wearing a beret & wooden cane in the other—his salt-and-pepper hair gathered into a seahorse.” Hwang is adept at capturing action and setting, as well as more intangible touches: “How far do you have to travel to arrive / at dying,” she writes in an elegy for her grandmothers. Some poems swoop across the page, riding sound and form; others, like “Latchkeys,” are pointed narratives contained by closed spaces. In that poem, the narrator is with her brother, waiting for her parents to come home. When their “headlights cast shadow / puppets against the living / room wall,” she and her brother scramble to seem responsible: studying biology, playing the upright Yamaha. Her father would head into the backyard “to hit / a golf ball on a string / while mother silently made / dinner: rice, kimchi, Spam / as we three listened / from different corners / of the house / to a tiny white ball / greeting iron.” A strong debut.