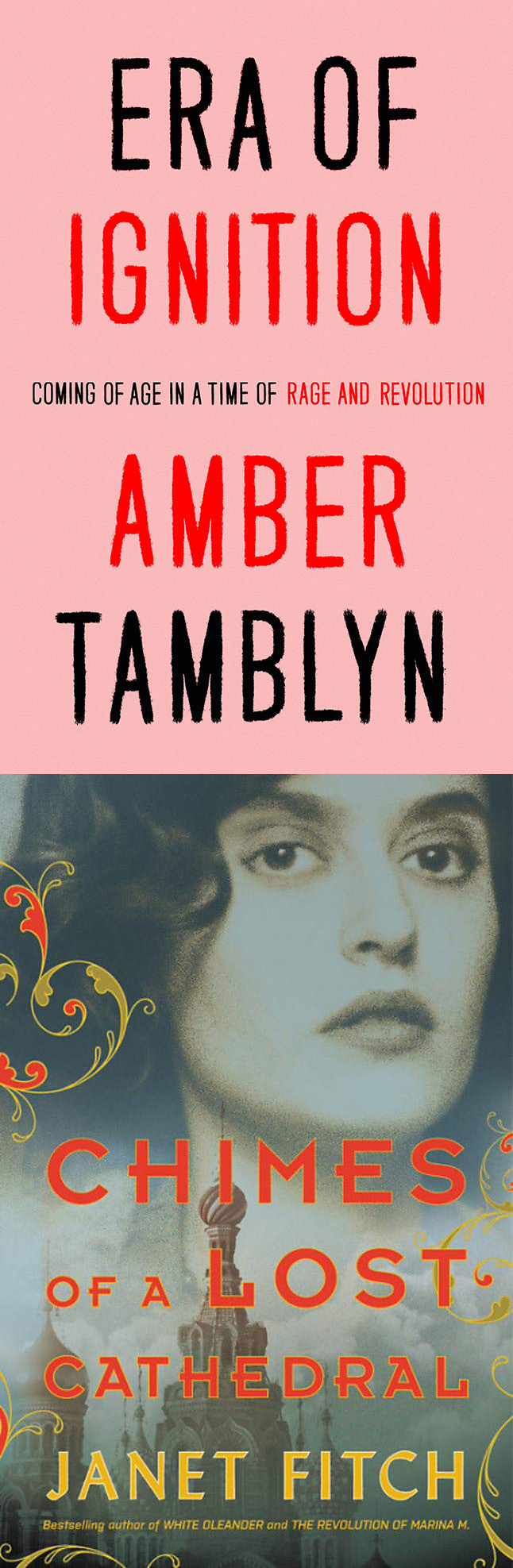

Amber Tamblyn and Janet Fitch first met at a tiki bar in Los Angeles in 2010, when Tamblyn was seeking the movie rights to Fitch’s second novel, Paint It Black, which became Tamblyn’s directorial debut. Since then, the two have had an ongoing conversation about feminism, politics, history, aesthetics, sexuality, cinema, tiki drinks, and life in our times. This year, both have new books—Tamblyn’s memoir of political awakening, The Era of Ignition: Coming of Age in a Time of Rage and Revolution, and Fitch’s novel Chimes of a Lost Cathedral, the second part of a duet set during the Russian Revolution, which began with The Revolution of Marina M.

The conversation continues here:

Amber Tamblyn: Janet, you have inspired a generation of feminist writers with works like Paint It Black and White Oleander. Your latest book, Chimes of a Lost Cathedral, the follow up to The Revolution of Marina M., is a full-throttle culmination of all the powerful ways in which you have written dangerously as an author, and also written dangerous female characters. What about this latest collection feels different to you than the stories about women you have told before?

Janet Fitch: My books have always had a feminist orientation, girls and women at agency in their own lives, grappling for meaning and a moral philosophy—though they would not have called it that. But up to recently, I’d written about my characters in a kind of isolation. Though they were impinged on by the structures of society, the thinness of social nets, or class issues as in Paint It Black, it was always about the drama of a few isolated individuals. Ingrid Magnussen, the rebel, was the only one who thought directly about the larger political structures.

But in the books set in the Russian Revolution, my young women, especially my protagonist, poet Marina, and her radical friend Varvara, think directly about society and its future, and their part in its unfolding. Women made the Russian Revolution. They were the ones who said, “No more.” When the women say it’s time, it’s time. They were an essential part of the new government—something that had not been seen in the world before, ever. I often use the voice of the bread queue as my Greek chorus, women expressing the temper of the times. Varvara at 19 is a responsible part of the Bolshevik government. Marina at 17 is already on her own, finding an absolutely new way of living in the world. Their friend Mina is the head of household, making decisions that will affect everyone around her. These women are forces in the world.

I think what all my books have in common is that I take the internal lives and moral development of women with utmost seriousness. What’s different in Marina M. and Chimes of a Lost Cathedral is the extent to which they are directly involved in the social upheaval, the way these questions become inescapable.

AT: This is so fascinating and true: Women have always been at the center of upheavals throughout history. We are seeing that now in the United States in politics as well, where women are finding themselves in unprecedented and necessary positions of power—especially black and brown women such as Ayanna Pressley and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez—Women who are our nation’s Varvaras and Marinas; agitators and accomplices to the much needed change we have craved for so long. It’s one of the things that drew me to one of your previous novels, Paint It Black, because it wasn’t just a love story or a grief story or a revenge story—it’s a story about a revolution. In that case, an emotional and spiritual one, driven by class.

JF: What was it that drew you to Paint It Black, made you itch to make it into a film—this gothic-Noir story about class and rage and female connection in the aftermath of a suicide? What made it worth fighting for?

AT: What made it worth fighting for was the fact that I knew it tapped into a kind of volatility and conflict story often not reserved for women characters portrayed in film—a volatility and complexity that transcends how, exactly, women are allowed to behave and be shown on screen. Paint It Black was about the ugliness of trauma, the underbelly of shame, and how complicated it is for women to confront these things, both in each other and in themselves. I find a lot of value and charge in the uglier sides of women’s thinking and behavior, and the parts of our violence that have not yet been explored or told. What do you find most thrilling and most difficult about the writing process itself?

JF: The most thrilling is when you’re writing and the suddenly, the angels sing. The writing takes you up and flings you into the air. There’s a rhythm and a sound—it’s like flying, it’s like jazz, what it must be to be Miles Davis out there playing a horn solo, feeling the music pouring through you. You can’t make it happen, but it does happen more often when you’ve been working very, very hard. Something takes over, you find you’re no longer standing on the ground, and that sound is coming through you. It’s the most glorious feeling, Like the Muse is breathing through you, through your hands.

The hardest is when you find that you’ve written yourself into a dead end, it’s not going to work, it’s never going to work, and you have to tear it all out back to the crossroads, where you first went wrong. That is a tough place to be. Also when you’ve been writing a long time, five years, seven years, and you wonder if this is ever going to come together, whether you have the chops to pull it off, and why did you decide to do this in the first place? I had many a moment like that.

AT: Where do you get your inspiration to write during this age of Trump and a world that continuously asks for women’s silence over their rage?

JF: Like other artists, I am by nature rebellious. Even as a kid, I was more likely to get thrown out of class for insubordination than sit there politely with my hand up in the air, hoping teacher would call on me. This has always been my inspiration to write—the rage to be heard, for others to see the world through my eyes. But my inspiration to write has been yanked into hyper drive by this current outpouring of lies and cruelty. It makes me want to slap truth up against it, to stir people’s humanity against the brutality.

Yet I’m a writer of fiction. Historically, poets have been literature’s first responders. Poetry is about the unpacking of a moment, turning it around in your hand, letting it catch the light like a prism. Essayists are also quick to respond. They’re already duking it out with this current disaster. But novelists are much slower. It takes us time to process, and find a narrative that can contain the bigger movements of the times. The danger for many fiction writers is to think we’re irrelevant if we don’t react immediately to every outrage.

But not every writer is a fast writer. What we have to remember is that the times are like the terroir in which our vineyards grow. If we’re writing deeply and honestly enough, our work can’t help but take on the flavor and the temper of the times and say something significant about it.

A mythic battle is being waged now, between truth and the lie, between real reality and claims of “fake news,” between science and commerce under the guise of religion, between reason and propaganda, women and people of color succeeding in making their power felt vs. the struggle of the old white male hegemony to maintain power. I think this epic struggle is going to touch everything being written now. Dark secrets will come to light, or be stuffed down again. Corruption will sink a family. A curtain will be torn back in a relationship. A man’s assumptions about the world will be broken open. The inspiration of this time will manifest in a million ways.

Women are breaking taboos—don’t talk about that! They’re rebelling against the old truisms. It’s the way of the world. Boys will be boys. We’re seeing how deadly those statements are and how foundational they are to our culture, as women hold a mirror to that behavior and say “we won’t pretend anymore. We will not be silent.” Even the act of holding the mirror is subverting the claim that our voices don’t matter.

Your last book of poetry, Dark Sparkler, examined the culture’s consumption of young women. Your first book of prose, the genre-bending novel Any Man, widened the discussion by putting men into a similar position—victims of not only of rape but the culture of rape. Now you’ve written what I would call a political coming of age memoir, a straight-up call to action, Era of Ignition. What was the progression here, what was the evolution?

Your last book of poetry, Dark Sparkler, examined the culture’s consumption of young women. Your first book of prose, the genre-bending novel Any Man, widened the discussion by putting men into a similar position—victims of not only of rape but the culture of rape. Now you’ve written what I would call a political coming of age memoir, a straight-up call to action, Era of Ignition. What was the progression here, what was the evolution?

AT: I think, similarly to you and many women like us, I also grew up feeling rebellious. I used to constantly get in trouble for, “my mouth,” for the things I would say as a kid, for the ways I pushed boundaries. Even from a young age as a child actress, I rebelled against my own industry and its sexism. I was already writing poems and chapbooks on the treatment of women and girls in Hollywood. The first poem I ever wrote, which you can find in my first collection of poems, Free Stallion, called “Kill Me So Much” was written at age 12 and is a complete confrontation with the fakeness and cruelty of the entertainment business. I was constantly doing this as a kid, in my writing, but also in life, when I felt something was not just.

AT: I think, similarly to you and many women like us, I also grew up feeling rebellious. I used to constantly get in trouble for, “my mouth,” for the things I would say as a kid, for the ways I pushed boundaries. Even from a young age as a child actress, I rebelled against my own industry and its sexism. I was already writing poems and chapbooks on the treatment of women and girls in Hollywood. The first poem I ever wrote, which you can find in my first collection of poems, Free Stallion, called “Kill Me So Much” was written at age 12 and is a complete confrontation with the fakeness and cruelty of the entertainment business. I was constantly doing this as a kid, in my writing, but also in life, when I felt something was not just.

Once when I was starring on the television program Joan of Arcadia, I said something publicly about then-CEO Les Moonves, criticizing the direction he had forced our show to go in because he wanted the teen demographic; he had tried to dumb it down by forcing us to do stunt cast (when you cast famous people simply because they are famous). Immediately my manager and agent and everyone on my team freaked out and told me I had to apologize to him. He was extremely powerful at that point and no one wanted him to feel called out by the star of his own television show—a young 21-year-old girl, for that matter. But I refused. Instead of writing him an apology note, I wrote him and double downed. I told him why I thought what he was doing was dangerous for the long-term success of the show and how it might alienate viewers and the real fans who watched us every week because we had an important story to tell, and were telling it in a way that no one had really done before. I tell you this story to say: I am with you on the rebellion stuff and believe that if any of us can afford to put our necks on the line, because of our privilege or access or whatever the reason may be, then we absolutely must. Especially if it’s in the name of protecting another person or protecting art.

Have you ever thought about writing something in another medium? Like, say, a screenplay? Or a book of poems?

JF: I actually went to film school for 3.5 seconds. A disaster. As a screenwriter, I’m a novelist. I think my first screenplay was 185 pages. I like to be god of my own planet. Screenwriting is a scaffold for other people to build on. Too spare and elegant a form for me. I’m in love with describing the world, being able to go wherever I need to go, invading the characters’ heads, using language in its beautiful, powerful extremes. I’d be more likely to write a book of poetry. I like the power and compression of it, the way you can unfold a moment, sink deep inside. I wrote all the fictional characters’ poetry in The Revolution of Marina M. and in Chimes of a Lost Cathedral. Marina M. in fact started out as a novel in verse. I write a lot of narrative poetry. Maybe I’ll come out of the poetry closet sometime.

AT: This is a brilliant answer. Is there a single instance you can remember early on in your childhood or your teenage years that propelled you into not just wanting to be a writer, but wanting to write the stories of dangerous women?

JF: I still remember my rage and my shame when a substitute teacher challenged my class to name a single woman writer, and I couldn’t think of any. How smug he was—until a girl in the front row raised her little hand and said, “What about Anaïs Nin?” He just stared at her…and changed the subject. That very night, I got my parents to take me up to Pickwick Bookstore and bought the boxed set of The Diaries of Anaïs Nin. I remember the picture on the side of the box, Nin with her strange, Kabuki-like makeup and false eyelashes. I lost myself in those books. She was the future I wanted for myself. Unapologetically sexual, a lover of beauty, creator of a new language—a woman treating herself as subject, rather than object. Determined to have the life she wanted, valuing her own search. I must have always held that picture of her in my mind. When I woke up in the middle of the night on my 21st birthday and decided I was going to be a writer, it was Nin I imagined. She stood for the dangerous woman, the self-driven consciousness, determined to find her own unique path, no matter what.

JF: I still remember my rage and my shame when a substitute teacher challenged my class to name a single woman writer, and I couldn’t think of any. How smug he was—until a girl in the front row raised her little hand and said, “What about Anaïs Nin?” He just stared at her…and changed the subject. That very night, I got my parents to take me up to Pickwick Bookstore and bought the boxed set of The Diaries of Anaïs Nin. I remember the picture on the side of the box, Nin with her strange, Kabuki-like makeup and false eyelashes. I lost myself in those books. She was the future I wanted for myself. Unapologetically sexual, a lover of beauty, creator of a new language—a woman treating herself as subject, rather than object. Determined to have the life she wanted, valuing her own search. I must have always held that picture of her in my mind. When I woke up in the middle of the night on my 21st birthday and decided I was going to be a writer, it was Nin I imagined. She stood for the dangerous woman, the self-driven consciousness, determined to find her own unique path, no matter what.

AT: This is such a badass story. And in your quest to find a woman writer to connect with, you turned your very own life into subject, rather than what could’ve been object. You became the propeller of your own trajectory.

JF: You’re a tireless battler for justice, yourself—I’ve seen you going out on the campaign trail for Hillary nine months pregnant, riding those buses. You just came back from the border where you spoke to women in a shelter for women and children recently released from detention camps. You talk to women everywhere you go, encouraging them to step up, or to help another woman step up. I have a collage in my study, portraits of women I admire for owning their own power, with a caption I found in some magazine, “What gave her the nerve to send back the espresso?” So, what gives you the nerve to send back the espresso?

AT: What gives me the nerve is watching the suffering all around me every single day, whether it’s immigrant children being separated from their parents on the first day of school by ICE, or whether it’s the suffering of the Amazon burning to the ground while we sit around making up jokes about the size of Donald Trump’s hands. I get it: we all need a check-out sliding scale. We all need a minute to focus on the shallow, or to be cruel back, in response to a cruelty we cannot control. But I have always tried to use my anger as part of my creative tool—no, weapon—and I know no other fight than the fight we are all in now. Because it is the one we have always been in. It is a fight that lives in my DNA, the make-up of every woman who lived before me so that I could exist today. And so I’m done with the politeness of swallowing my fury for the comfort of others. If the Amazon is going to burn to the ground, then so am I. And I will do everything in my power to continue to show up for the world, and other people who need showing up for, even if the world does not always give that in return. Silence is not death. Complacency is.

I’d like to close this interview by writing a short story with you, based on some themes in our interview, in real time. You heard me. Just something off the tops of our heads. Let the readers of our interview see if they can figure out where I end and you begin. Ready? Here we go:

AT and JF: Edwin sat on his porch drenched in sap and sweat, staring across the new tree line he had spent all day cutting for his back yard. Without those few extra trees in the way, you could really see solid skyline. Edwin took a sip of something cool and wiped his dripping forehead with something soft.

In the distance he could hear the ground’s crunch, the sound of something moving up through the woods. Deer, maybe. Although deer don’t usually make that much sound. A bear, he thought. But what bears are in this area? Above the ground, high up in the air, Edwin heard small branches begin to break from their larger trunks. Edwin paused his heavy breathing to listen closer, to try and hear what was coming. All around him, branches severed themselves, large and small, and fell to the ground making the sound of giant birds crashing to Earth. Edwin rubbed his eyes, trying to understand what was happening. Was he dreaming? He stood up, the glass of something cool dropping from his hands and shattering on the ground. He looked around at his beautiful trees, now branchless. Bare.

One by one, each branch began to move. To lift their own wooded bodies. To stand, like men. Edwin stepped back and braced a hand against the doorframe of his house, his mouth frozen ajar. He watched as an army of twigs slowly made their way toward him, as if alive, as if embodied. Some even rolled. One by one, they piled themselves on top of each other right in front of him, at the bottom of his steps. They piled for so long, and so high, he could no longer see his precious sky. When they were finished, a silence struck the entire forest. Not even a bird called to its mother. Not even the stream heckled its rocks. Edwin began to tremble, then cough. He coughed until he felt something loosen from his throat. He dropped to his knees lunging his body forward, until finally from the depths of his throat, out fell a matchstick.

What did they want from him? He was sorry! He was so sorry. He hadn’t realized this could happen. They were just trees! Blocking his view of the city. That million-dollar view. Actually $2.5 million but this was not the moment to quibble. A few trees more or less, he’d thought—what difference would it make? A little more yard, a little more for him. Don’t do it Daddy, little Rachel had said, crying, hugging the whatever it was, crabapple. Winesap.

He knelt and wept. Don’t kill me. He’d loved those trees, he didn’t know how angry they would be, that they would strip their very limbs in fury. So he’d cut a few, editing the view. Isn’t that what people called it? Buying the skyline, a little more light, a little less lawn litter, those berries that stuck to the kids’ feet, the leaves he had to rake in the fall, those fucking little apples.

Now the branches where whispering to each other. Rattling their leaves, shaking as if there was a wind through this ghastly wall of torn limbs—though there was no wind.

The match ignited itself. It stood up on his back step, the smallest tree of all.