1. Ghosts

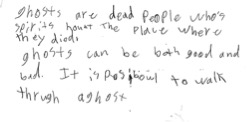

A few years ago, on a hike in central Oregon, my niece found this scrap of paper alongside the trail. It reads: “ghosts are people who’s spirits haunt the place they died. Ghosts can be both good and bad. It is posibowl to walk thrugh a ghost.”

Later, while we were trying to get our various daughters to bed, I pocketed the note. I figured it was most likely for me, for my purposes. It was sent to me.

Please understand: Ghosts are mysterious. But nothing in this message is particularly new to anyone familiar with such spirits. These sentences simply list some characteristics of ghosts. What is haunting, here, is what is unknown—who wrote this note, and why, and to whom? Is the “posibowlity” of walking “thrugh” a ghost meant to be reassuring or provocative? Are these words reacting to a specific situation, or are they meant as part of a more general definition?

Herein lies one fascination of a found text: its disconnectedness. We don’t tend to know the writer, nor the intended recipient, nor the intention. The text comes from nowhere and finds us as much as we find it. It haunts us. These words await a reader, out in the wilderness, eager to be read.

2. Libraries Are Magnetic

How many times have I wandered through the stacks of a library, beset by exhaustion and daydreams, only to pull out a random book and find that this text has been waiting to find me? Libraries, a kind of zoo for texts, can feel magnetized this way. All of those words, pressed tightly together, hoping to be opened, to be witnessed.

I used to—in order to signify my seriousness—go to the University of Utah library late at night to study my high school biology homework. This was 1984. Bleary-eyed, I’d wander into the small area where texts concerning UFOs and Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster resided. (True, our disposition brings us into a vicinity.) There, my eyes snagged on, my hand reached for The World of Ted Serios: “Thoughtographic” Studies of an Extraordinary Mind. Inside this text, I learned about a man who could, by staring into the lens of a Polaroid camera, produce images on the film of things and places far away. In a windowless room, he’d stare fixedly at the camera, hit the shutter, and out would come visions often beyond his experience and slightly askew of his predictions (he’d promise a dinosaur, come up with a grainy picture of a rhinoceros in a museum).

I used to—in order to signify my seriousness—go to the University of Utah library late at night to study my high school biology homework. This was 1984. Bleary-eyed, I’d wander into the small area where texts concerning UFOs and Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster resided. (True, our disposition brings us into a vicinity.) There, my eyes snagged on, my hand reached for The World of Ted Serios: “Thoughtographic” Studies of an Extraordinary Mind. Inside this text, I learned about a man who could, by staring into the lens of a Polaroid camera, produce images on the film of things and places far away. In a windowless room, he’d stare fixedly at the camera, hit the shutter, and out would come visions often beyond his experience and slightly askew of his predictions (he’d promise a dinosaur, come up with a grainy picture of a rhinoceros in a museum).

For all these years, this ability of Ted Serios—widely considered a charlatan, he was never caught out; also, the relative failures of his “successes” have the convincing, hazy feel of authenticity—to somehow conjure something hidden from within oneself, to cast it out into the world, to surprise oneself and others, has fascinated me. It’s served, I believe, as the most aspirational example of what I hope to accomplish when writing fiction.

3. Journals and Diaries

My older sister’s diary had a brass lock that was eminently pickable. My ex-girlfriend just used a spiral notebook. In the Mishima novel I’m reading now, Thirst for Love, the protagonist keeps a “false” diary in a place where her father-in-law will read it and be misled. Don’t get me started on The Key! Sometimes it feels that writers of such private texts are always anticipating a reader. These words whisper and call.

My older sister’s diary had a brass lock that was eminently pickable. My ex-girlfriend just used a spiral notebook. In the Mishima novel I’m reading now, Thirst for Love, the protagonist keeps a “false” diary in a place where her father-in-law will read it and be misled. Don’t get me started on The Key! Sometimes it feels that writers of such private texts are always anticipating a reader. These words whisper and call.

I have often been such a reader. Reading with the tension that the doorknob might turn, footsteps might approach; fingers trembling, eyes reading faster than they ever have, trying to get it all in and get away as soon as possible.

We always want to read what is forbidden, and it’s also delicious to write something that’s secret, forbidden to others—perhaps with the hope that the right person might come across it and see inside us, or think they have.

It’s likely that the best and most helpful texts I’ve read in the last 10 years are the journals of the American watercolor painter Charles Burchfield. First it was his paintings that held me in their thrall, his specific ability to infuse the natural world with sound and light and spirit; then, in reading about his own process and path, I learned that he desired to be a writer as much as he did a painter. His journals, combining the quotidian and the visionary, dreams and family life, dogs and weather, have showed me new ways to write and work. Perhaps this passage, from 1911, has been the most illuminating:

In writing a diary, I first thought that only events should be written; then gradually I began to put descriptions in which led me to describe my feelings at seeing different scenes and objects; now I think I ought to put in my imaginings, for they are part of a person’s life.

4. Are Epitaphs Found Texts? Are They Addressed to the Living, or to God, or to Both?

Recently, I’ve been discussing gravestones with my mother. When she chooses an epitaph, is she imagining some stranger finding it and gleaning something from those words cut into stone? Is she summing things up for the people left behind or leaving a message for eternity?

Charles Burchfield once buried a dead bird with a note that read Music exists in other forms. In his journal, he writes, “I saw a reflection of a falling cherry petal in a window and thought how like it was [to] the bird’s life.” He imagines that a “fairy, building a house of the wings of a moth, might use the transparent spots in the wings as windows. What would flowers look like seen thru them!”

Not long ago, a dead hummingbird appeared, resting on its back, on a small table just outside our window. I saw my daughters pick it up and carry it around; they were talking to it, but I couldn’t hear what they were saying. I stood inside the house, close against the curtains where they couldn’t see me, and watched them. They leaned their faces close to the bird, whispering. They set it gently down.

Friends of mine once belonged to a church in Montana whose parishioners believed we come from beyond and live many lives. One of their practices was to listen carefully to a child’s first words, and to hesitate in correcting them. Our tendency, when teaching a child to speak and think, is to bring a child’s understanding into alignment with our shared, compromised way of communicating; yet children’s first words, often incomprehensible to us, might well be coming from a truer place, or may speak from the experiences of a previous life.

I watched my girls with pride and tenderness, it’s true, but also with envy. I knew that if I slid the glass door open, their whispering would stop; they would look up with me with innocent exasperation and quickly cease whatever they were doing.

Later, I found the grave where they’d buried the hummingbird, back against the fence, next to the rhododendron. A plank of wood leaned there, a heart drawn on it with black marker, the artifact of their words, left behind, allowing me access to their experience:

5. Letters Are Emotions Sent from one Person to Another

The suspicion that diary-writers have an audience in mind holds true for the “collected letters” of various literary figures. It’s similar to when you’re having a conversation with someone and they’re speaking especially loudly, so someone else, nearby, can hear them and be impressed. Such letters offer the façade of an intimate conversation yet are written not so much for the intended recipient as for some rarefied posterity. It’s easy to read Hemingway’s letters to Fitzgerald—full of puffery and put-downs, driven by insecurity—and to imagine him chuckling as he filed away the carbon copies.

Sometimes, though, we gain access to the actual intimate writings of another, words we were never meant to read. If the writer is someone we know, all the more delicious. (Access to another person’s emails or texts holds a different energy for me; less romantic and more political?) Letters are composed, freighted.

A few years ago, an ex-girlfriend told me she had all the letters I’d ever written to her and wondered if I wanted to read them. I equivocated, as I was working on a project about those years, reacting to artifacts of my past; ultimately I told her not to send them, as the idea made me feel guilty—as if the pursuit of a story was allowing me to behave badly, to continue a relationship, in a fashion, 20 years after I’d married another—and because I’d written those letters explicitly to her, back then, not for me to peruse or use many years later.

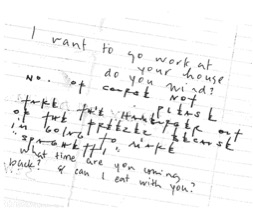

And yet she sent them, despite my protests, stipulating that she wanted them back. The address she had, however, was far out of date, and so she sent the letters to a house where I no longer lived. They were lost for two months before I (after a desperate period of badgering mail carriers and the damaged occupants of my old house) managed to recover them. Eight years of letters, beginning with a note, a correspondence written in a library, at the beginning of our relationship:

These letters continued into our first year apart, when I worked on a ranch in Montana (“I’m sitting on my steps and a sparrow’s building a nest above me, dropping little pieces of mud”) and covered various hopes and stumbles (“I want to live somewhere with a real table. What do you wish we could talk about that we can’t because everything is not more ok?”) and documented various times I failed to have any emotional maturity whatsoever (“It’s hard to write—either it seems like I’m avoiding something by passing on news or I’m complicating an already complicated problem. I feel I’m letting you down by not being clear enough or not saying something I should have”).

I found reading these letters quite disorienting. Not only did I not remember writing these words, they often seemed—syntactically, experientially, and in terms of intention—to be written by another person entirely. How to account for this alien, uncanny feeling?

Also, it’s impossible to deny that these letters are simply better, in style and tone and emotional force, than any fiction that I wrote during those years. Why is that? Part of it, I believe, is that they are truly intimate and slightly desperate—I am not worried about communicating with the world, but only in trying to convince her to be with me, to help me be less lonely, to understand who and where I was. They are suffused with inadequacy, and with yearning.

6. What I’ve Found

The reasons I’m drawn to found texts, the excitement I feel when a text finds and resonates inside me, are all related to the kind of fiction I wish to write—it’s no coincidence that the examples above infused and provoked my recent novel, The Night Swimmers—and to read.

The reasons I’m drawn to found texts, the excitement I feel when a text finds and resonates inside me, are all related to the kind of fiction I wish to write—it’s no coincidence that the examples above infused and provoked my recent novel, The Night Swimmers—and to read.

I want fiction that is proof of another person, another time, yet whose source is mysterious, where the intention cannot be easily traced. I want texts that contain secrets, that feel forbidden; I want to feel the excitement of gaining access to something that wasn’t initially meant for me. I love words that seem to find me when I’m not seeking them, that seem to seek me out of intuition and destiny. I desire to feel yearning, words straining to communicate in ways that are intimate, direct and—while being oblivious to a wider audience—somehow eternal.

Image credit: Unsplash/Micah Boswell.