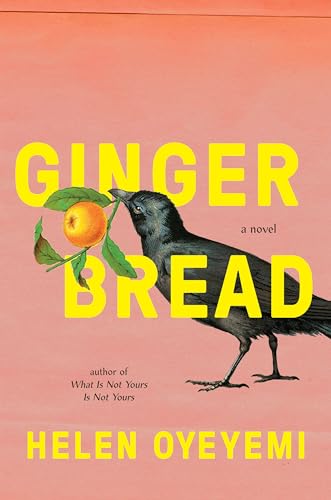

How do you solve a problem like gingerbread? That’s the question Helen Oyeyemi found herself answering while writing her sixth novel, aptly titled Gingerbread. The illustrious author’s follow up to the short story collection What Is Yours Is Not Yours is a challenging book. It was challenging for Oyeyemi to write. It is challenging to describe. It is challenging to read—in the sense that it reads like very few books written this millennium.

It is also a rewarding book. Oyeyemi wrote Gingerbread in two of her favorite cities, places where she says she daydreams more recklessly. The result is a story about a mother who loves gingerbread more than nearly anything and her family’s mysterious heritage.

The book, unlike her loose retelling of “Snow White” in Boy, Snow, Bird, doesn’t directly link to a fairy tale—in this case “Hansel and Gretel.” Rather, it asks why gingerbread was used by the witch to lure the two children at all.

The book, unlike her loose retelling of “Snow White” in Boy, Snow, Bird, doesn’t directly link to a fairy tale—in this case “Hansel and Gretel.” Rather, it asks why gingerbread was used by the witch to lure the two children at all.

I spoke with Oyeyemi about creating a problem book, what excites her about reading, and how Prague has influenced her career.

The Millions: Whenever most people describe your work, they compliment your “lyrical prose.” What does writing lyrically mean for you? Or is that even how you describe your writing?

Helen Oyeyemi: I don’t know how to describe it. I don’t really recognize the lyrical and am always a bit puzzled by that. Unless it means lyrical in the way that Emily Dickinson writes a lyric, which is that you have a rhythm to it, and you have unexpected or abrupt breaks and it swerves into another image. I’m not quite sure what the other description could be.

TM: I was talking to a friend who is a poet last night and he said critics or fans write lyrical prose when the beauty of the work overwhelms them and they can’t describe it.

HO: I like that people find it beautiful. I worry I don’t do enough to create beauty.

TM: Your work captivates me, and I find myself rereading sentences. Not because it was unclear and confusing, but because it was so memorable. I recall an interview where you said you wince when you think about your future readers because you write challenging structures or themes or plots. Is that your goal? To challenge readers?

HO: With every project, I want it to be something fun to do, but also very difficult to do. I suppose the more books I write, the more interested I am in the process. The sense of exhilaration as I write. I suppose it leaves me less interested in the end result, but what I am hoping is that if I enter that space of exhilaration while writing, that the reader will feel the same way even though it is difficult. I don’t want to say difficult. It’s not the easiest read, but hopefully reading it is freeing for the reader.

TM: How did you want to challenge yourself this time around?

HO: I feel surprised by this book in a good way. It feels to have more heart than the other books. I wanted to write about gingerbread. I wanted to take the symbol of gingerbread you see in all of these stories. The idea of coziness, and it has a certain seasonal aspect to it. I wanted to take that and figure out what it means, but gingerbread was sort of resistant to that.

It turned into a story of all sorts of things like property and the values of what you have to offer. Whether the value is dependent on one person liking it—for example, Gretel liking the gingerbread, or not a lot of people liking Harriet’s gingerbread.

I wanted to write a story about gingerbread, but gingerbread kept shifting to the side, telling me why don’t you write about this instead.

TM: Did gingerbread lead you down paths that never made it into the book?

HO: I just recorded the audiobook and the director and I were talking about the book and the tone I would read it in. I kept referring to things that didn’t make it into the book and the director must have been wondering what I was talking about. There was a whole university I wrote about that isn’t in the book. I suppose it was like I built a gingerbread house and nibbled parts off for my own consumption and just offered the rest.

TM: You mentioned gingerbread is found a lot in stories throughout history. “Hansel and Gretel” is perhaps the most popular and might come to mind with your book just with the title. Especially considering Boy, Snow, Bird was linked to “Snow White.” What draws you to the coziness of fairy tales?

HO: This one was less of a fairy tale and more of a problem book. The problem was trying to figure out what gingerbread means. It does play a role in “Hansel and Gretel,” but the question is why was the house made of gingerbread. What was it about gingerbread that makes it inviting and menacing at the same time? It’s as if we’re saying home is delicious but also scary at the same time.

I wanted to figure out why someone would have gingerbread as their gift to the world. That is Harriet’s gift; she gives gingerbread. She is proud of her gingerbread. The problem of the book is her figuring out whether it’s a good thing, a bad thing, or a neutral thing.

TM: On the idea of home, Prague has been your home for quite some time now.

HO: Six years.

TM: Six years. Does that mean this is your first “Prague novel?”

HO: The last one came out while I lived here. It took a long time for Czechness to come out in my writing. I sometimes feel a bit impatient with that because it always takes ages for where I am to come up in my writing. It’s a long process.

I don’t think this book is all the way Czech. I think the all-the-way Czech book is a little way down the road. This was my first book where I was happy to hold hands with the Czechness.

TM: What does that mean for you?

HO: I tried to find a way to inhabit or give a nod to Czech writers but didn’t want to create something that was not genuine. I have to go slowly with it.

TM: Was Druhástrana—a fictional country that only Czech citizens seem to believe in—always a part of your story from the beginning?

HO: The notion of the country was part of the fun of writing it. Living here, it does seem plausible that there would be a country tucked away in the vicinity of here that only the Czechs know about. The Hungarians as well, but they deny it. That country was always there.

TM: And Gretel?

HO: It is like I was saying about Harriet trying to figure out what her gingerbread is worth. There has to be some sort of market for it. Unfortunately for Harriet, she spends a lot of time weighing Gretel’s opinion against everyone else’s and which to trust and which to value. Gretel had to be in the book. There had to be a lover of gingerbread.

TM: In addition to the mysterious country and Gretel, I felt this book indirectly played with time. It’s a very modern book, but the gingerbread made me feel like I was in a different era.

HO: I think just the presence of gingerbread in the story is what does that. I feel like I am about to start sounding like a documentary filmmaker, but gingerbread has been with us for a very long time. Every time you eat a piece of gingerbread, it is like you’re tapping into a part of this ancient baking tradition.

TM: Earlier, you mentioned this book being a problem book. What is an example of a problem book as it relates to Gingerbread?

HO: There is a book by Barbara Comyns called The Skin Chairs and that is a problem book as well. Nothing really happens except this girl sees these books covered with human skins. Nothing really happens except this girl realizes one day she is going to die and just be skin. That’s what I mean when I call something a problem book. Nothing happens, but everything happens.

HO: There is a book by Barbara Comyns called The Skin Chairs and that is a problem book as well. Nothing really happens except this girl sees these books covered with human skins. Nothing really happens except this girl realizes one day she is going to die and just be skin. That’s what I mean when I call something a problem book. Nothing happens, but everything happens.

As I was writing Gingerbread, I realized it was going to be about Harriet wanting to figure out what she wants for her gingerbread and I understood it was going to be a problem book.

TM: This book is very hard to succinctly describe. Is that how you would describe it then?

HO: I was trying to explain it to a friend then started trailing off and said it was more about how it’s told than the story itself. I think the pitch I am going with for now is that it is a very long bedtime story.

TM: I think that idea of how the story is told rather than the story is the one thing I would come to expect from you as a writer.

HO: That is entirely the point of being a writer. We are all just trying to say what it means to be alive right now. The only invigorating thing is the difference between each writer’s method. I could read anything, like Harriet reads the Farmer’s Almanac. It just depends on how you’re telling it to me.

TM: Do you read publications like the Farmer’s Almanac while writing?

HO: Yes. Tone is just so lovely. There is something that lives on for so long. I was reading Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, which is just what to do as a housekeeper. Her voice still comes across the pages after all these years. I felt strengthened by that.

HO: Yes. Tone is just so lovely. There is something that lives on for so long. I was reading Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, which is just what to do as a housekeeper. Her voice still comes across the pages after all these years. I felt strengthened by that.

TM: Where do you take your writing moving forward?

HO: The next book is going to be a train book. I think about the project and I think who I want to inhabit the space and drive the story.