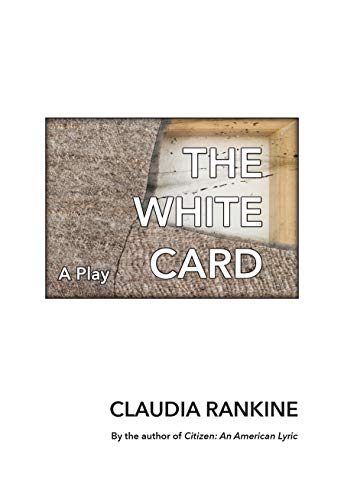

On March 19th, poet Claudia Rankine published her debut play, The White Card, which, according to Graywolf Press, poses an essential question: Can American society progress if whiteness remains invisible?

The Millions sat down with Rankine to discuss the differences between writing for the page and for the stage, and watching her work take life in the theater.

The Millions: What made you decide to write The White Card, and specifically to format it as a play?

Claudia Rankine: Our inability to have conversations is manifesting as a national crisis. As poet T.S. Eliot writes, we must “after tea and cakes and ices,/ Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis.” Since plays can perform an imagined possibility, I wanted the genre to help me see what a continued discussion around race could look like.

TM: Why publish the play in book form a year later? In particular, why now?

CR: Never has it seemed more urgent for us to begin to trouble the conversations we attempt regarding a dynamic that is costing Americans and others around the world, their lives and livelihoods. The book seemed to me a beginning look at the anxieties and fragilities we encounter in these encounters.

TM: Did you think of this play as an extension of your work in Citizen: An American Lyric, or as something completely different? Why?

CR: The play would not have happened were it not for the discussions about Citizen that I had around the country in Q&A sessions, onstage interviews, and conversations with various artists and thinkers. It was only then that I understood our limitations when trying to discuss issues of racial difference face to face.

TM: What are some of the differences between the way you write poetry and the way you write for the stage?

CR: Playwriting is a deeply collaborative endeavor. The work of The White Card could not have been made without the efforts of the dramaturg P. Carl, the director Diane Paulus, and the rest of the crew. The text shifts based on the voices and personalities of the actors, their lines of inquiry into the characters they were embodying. In many ways I feel like I entered the room with an idea, and it was only through the interaction with others that it came into fruition.

TM: The play premiered staged last year in Boston. What are your thoughts on its staging?

CR: The staging of the play was brilliantly realized by the scenic designs of Ricardo Hernandez, the costume design of Emilio Sosa, the lighting design of Stephen Strawbridge, and the sound design of Will Pickens. I communicated to the designers that I wanted people to understand the structural nature of whiteness, and in this way the set (a white box) became a metaphor for troubling, immersive structures of white dominance.

TM: Do you think the premiere’s location—in Boston, which is often called, as the Boston Globe has itself noted, the country’s “most racist city”—was appropriate, considering the play’s themes? Did you think it might have prompted a different audience response in another city?

CR: Though Boston holds the dubious categorization, I think the play could have opened anywhere in the United States, given that we are talking about structural segregation that has predetermined the nature of our institutions and interactions.

TM: Are you working on any other works for the stage presently?

CR: I am presently working on a monologue about illness with affect theorist Lauren Berlant, who recently published The Hundreds.

This piece was produced in partnership with Publishers Weekly and also appeared on publishersweekly.com.