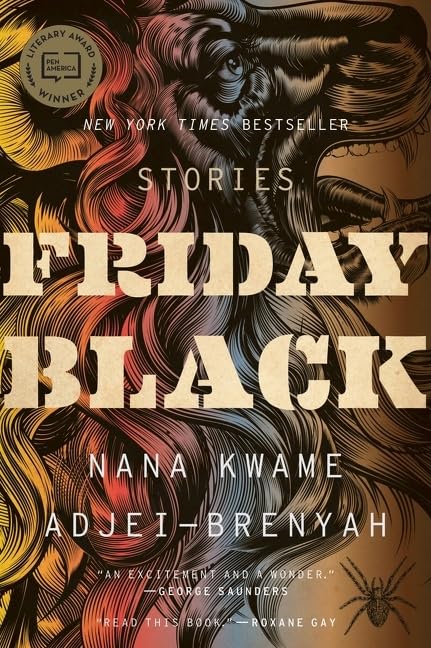

Very few short stories have grabbed me by the collar and shook me like “The Finkelstein 5.” Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s debut collection Friday Black opens with the story that has a vividly grotesque image of a young girl whose head has been sawed off. It’s not for the faint of heart; however, neither is most of reality anymore. Adjei-Brenyah’s collection is filled with tough passages, but it is one of the most vital collections in recent memory.

The author was an undergraduate student when Trayvon Martin was murdered by George Zimmerman, and the shooting—and subsequent acquittal—was a turning point for him. He grew up in a suburb of New York and was raised by immigrant parents for whom reading was a focal point. He told stories but never saw himself as much of a writer until his early 20s. From there he obtained his MFA from Syracuse under the tutelage of George Saunders. It’s not as if his entire life was preparing him to write a necessary and sharp collection of stories that dissects our world; but that’s where he ended up.

Throughout Friday Black, he uses graphic realities combined with surreal settings to explore racism, identity, consumerism, and family. The work is timely, but Friday Black was also timely a decade ago. Two decades ago. Three decades ago. You get the picture.

I spoke with the author just after he was announced as a National Book Foundation “5 Under 35” honoree about radicalizing imaginations, crafting realism through the surreal, and coping with tragedies both large and small.

The Millions: This is your debut collection, you have a few stories published already, and you were just named to the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35. How are you handling it?

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah: When I was writing these stories for a long time, my main concern was to be acknowledged as a writer. Being legitimized by other people. Part of me still has that for sure. That 5 Under 35 was something I of course wanted eventually, and to get it the way that I did with a debut is great. I hoped to have an impact like other writers, but I didn’t know what that would actually look or feel like. It’s just getting a bunch of emails and tweets. It can get overwhelming.

TM: Were there writers of color or writers who were children of immigrants that you read and were inspired by?

NKAB: When I was growing up, I read anything that was around me. I read some not-great fiction with simple plots. It wasn’t until I was in college that I started reading with intention and seeking out authors. My parents did make reading a priority. They would drop me off at the library and pick me up close to closing. My older sister made reading cool in my house. I started off reading anything that hooked me and excited me. Whatever that looked like.

TM: So you started reading with intent in college; did you start writing then as well?

NKAB: I had written for a long time for myself. My friends and I kept stories up orally. We traded these serial fictions by memory. I wrote fantasy-like stories because that’s what I was into at the time. Writing was my safe space. It was something I could do that was free. It was something that people could not take away.

In early high school, I was writing. I was encouraged by my English teachers. Those were my strong classes in school. They told me I could write and I felt like I was good so I worked on my writing. It wasn’t until later on in college that I wanted to be a writer. I was never around other writers so I didn’t know that’s what a human like me could be.

TM: These serialized stories you told with your friends and those fantasy stories, is that where some of your futuristic tinges in this collection evolved from?

NKAB: I like creating premises that serve my purposes. Whatever I need the world to do, I create something to do it. Sometimes that needs to be way far in the future; sometimes it needs to be right here and right now without any surrealism. I try to imagine a space that would squeeze absolute emotion from my characters. I have no qualms stepping out of the bounds of strict reality. I don’t feel that’s a prerequisite for having to engage with politically charged moments in writing.

TM: Throughout this collection, I kept coming back to real-life examples of a young black man being murdered by a white man. Especially with “Zimmer Land” and George Wilson Dunn in “The Finkelstein 5.” Did you draw from anything specific or take the emotions from the countless senseless murders that continue to happen?

NKAB: I very intentionally named that story “Zimmer Land.” The name in “The Finkelstein 5” was intentional. I did draw from Trayvon Martin. That happened when I was in college and was a big shifting moment in my consciousness. It was a moment for me that planted a seed that would grow into some of these stories.

I also think “The Finkelstein 5” draws emotionally from all of these murders. People might think of it as hyperbole that there is a constant fear that any black death’s [perpetrator] will be acquitted. All of these people get shot or killed with a chainsaw, you’re not any less dead. The brutality that comes within my stories is an accumulation of all of these events that happen again and again and again. People might think of it as surreal, but my stories connect that constant state of emotion.

TM: You and I are basically the same age—I had just finished my undergrad when Trayvon Martin was murdered. I feel that people in their late 20s have had a constant rotation of major tragedies. Not to say any other generation didn’t. We lived through Columbine and 9/11 as children. The Iraq War and war on terrorism dominated my teen years. We went from Bush to Obama to our current president. Natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina seem to pop up every year. Did you use writing to cope with things like this?

NKAB: I use writing to cope with everything from national tragedies that are too big for me to grasp to the fact that I embarrassed myself in a music class in 6th period. Short fiction lets me put a macro-micro feeling into it. This bad thing happened to me in my personal life, but these big events are happening as well. I rarely wrote to cope with the big picture when I was younger. My work now is a response on a personal level to help me cope and respond.

TM: I feel like a lot of people are going to say this collection is “timely,” but in reality, you were probably working on these stories for half a decade or a decade. I can’t call it “timely” because is there ever going to be a time when these types of stories won’t be timely?

NKAB: I had a recent interview that asked me what word I hate the most to describe my writing. I used “timely” for exactly the reason you said. Everyone always refers to our current political moment. A lot were written five or six years ago. They’re all pre-Trump. These problems are pervasive and inherent to our society.

I do think there is something purposeful in writing. I do think it can be helpful and employed to help us learn. We can challenge each other and help each other be better. These are problems that have been internal.

I hope my writing can radicalize people’s imagination. My writing is almost a surreal negative. It’s the worst version of what we can go through. The resistance that some people feel to my stories is natural. Hopefully they’ll start to think about how they can do better. It’s a reality of life. Young black men are being murdered. Women are being sexually harassed. I think fiction can help us ask questions about what we can do. Some people haven’t even gotten to the point of acknowledging a problem exists.

Fiction can help make people empathetic. Fiction is not the answer to the world’s problems but I believe fiction can help make the world better.

TM: Every story in my copy of your book has notes. Not only about the writing, but as talking points I can share with my conservative family members or friends. Or even my super liberal friends’ little siblings who are beginning to pay attention to the world around them.

Since this is so “timely” (and was two decades ago but hopefully not two decades from now), where do you take your writing from here?

NKAB: It’s hard to think about. It means a lot you would say that about this fiction. It means a lot that people who aren’t my Facebook friends will read my stories. It’s still so early on for me in the writing world. I’m learning to not let this moment affect my writerly growth.

I need to stay grounded.

There is still such a far way to go. I’m going to try my best. I want my fiction to influence people in positive ways. To not feel alone. To try to be better. I hope these stories make people feel it is not impossible.