1.

Cotton Mather, third-generation New England Puritan divine, wrote in his 1721 pamphlet India Christiana that “we have now seen the Sun Rising in the West.” Mather’s conceit was allegorical, yet an aspect of poetry’s power is its refusal to let you forget the implications of the literal. In a fascinating bit of ecumenical consilience, an Islamic Hadith agrees with Mather that Judgment Day awaits for when “the sun rises from the West.” Both demand their hypotheticals. A westerly dawn, the blood-skied evening transposed to morning, would be such a strange sight that one wonders if the human mind would even be able to initially comprehend what was seen. An apocalypse of the subtle unexpected.

Mather’s vision inspired my dissertation and would dominate the better part of a decade for me. The western dawn was striking to me, so arresting, that my reasons for that academic work flowed from this origin (even if the process was far from uncomplicated). Justifications for what one studies are always personal, but from that one line I built a personal cottage industry of bringing up Mather in incongruous circumstances, a familiarity with the stodgy, pudgy, wig-bedecked Calvinist I wouldn’t have anticipated.

A dissertation is normally a method of working through some stuff. For me, among other things, I was working through sunsets. Technically I was writing about early modern representations of western migration, but I was really chasing the sun. Dusk feels like weight to me, when apprehension and beauty are comingled, an hour that prefigures death. I would cite Barbara Lewalski on Protestant poetics and Leo Marx on technology and the pastoral; Louise Martz on medieval traces in Renaissance lyrics, and Sacvan Bercovitch on Puritanism, but fundamentally all of that was just filler. I simply wanted a method to approach the dusk.

2.

I’ve not been particularly drawn to Jack Kerouac since high school: With maturity, that affection fades. Still, On the Road has some beautiful passages, such as Kerouac’s description of a southwestern sunset: “Soon it got dusk, a grapy dusk, a purple dusk over tangerine groves and long melon fields; the sun the color of pressed grapes, slashed with burgundy red, the fields the color of love and Spanish mysteries.” Kerouac can be florid (what are these “Spanish mysteries?”), and he inserted four references to wine in just one sentence. There is something to that comparison though, making explicit the strange intoxication of the sun as it collapses from the sky. A sunset can be both joyful and dangerous. If the witching hour is when ghouls stalk the earth, then the gloaming period is reserved for those creatures called duende in Spanish, that vital mystery which Federica García Lorca claimed is impregnable within “everything that has darkness” in it. Pablo Neruda wrote that “I love you as certain dark things are to be loved, / in secret, between the shadow and the soul.” Dusk is the hour of encroaching darkness and shadows; it’s when souls are most solid. Those are maybe the Spanish mysteries which Kerouac intuited. Describing a sunset is difficult, better to describe something else ineffable, like love or a shadow.

I’ve not been particularly drawn to Jack Kerouac since high school: With maturity, that affection fades. Still, On the Road has some beautiful passages, such as Kerouac’s description of a southwestern sunset: “Soon it got dusk, a grapy dusk, a purple dusk over tangerine groves and long melon fields; the sun the color of pressed grapes, slashed with burgundy red, the fields the color of love and Spanish mysteries.” Kerouac can be florid (what are these “Spanish mysteries?”), and he inserted four references to wine in just one sentence. There is something to that comparison though, making explicit the strange intoxication of the sun as it collapses from the sky. A sunset can be both joyful and dangerous. If the witching hour is when ghouls stalk the earth, then the gloaming period is reserved for those creatures called duende in Spanish, that vital mystery which Federica García Lorca claimed is impregnable within “everything that has darkness” in it. Pablo Neruda wrote that “I love you as certain dark things are to be loved, / in secret, between the shadow and the soul.” Dusk is the hour of encroaching darkness and shadows; it’s when souls are most solid. Those are maybe the Spanish mysteries which Kerouac intuited. Describing a sunset is difficult, better to describe something else ineffable, like love or a shadow.

3.

3.

Kshudiram Saha in The Earth’s Atmosphere: Its Physics and Dynamics provides a soberer explanation of sunsets, writing that the intensity of a sunset is correlated to several different factors, including the process of the scattering, reflection, and absorption of light related to the size of the “particulate matter that may be suspended in the atmosphere” where “the degree of scattering depends upon the size of the molecules of particulars compares to the wavelength of the incident beam.” Saha explains that “light scattered is inversely proportional to the fourth power of the wavelength of the incident beam,” so that at sunset the “sky turns yellow or red because most of the blue is scattered away and lost” having to now pass through a “much thicker and denser layer of the atmosphere.”

Sunsets, with their panoply of blues, bouquets of yellows, bushels of oranges, and engulfment of reds, will move through a specified choreography as the earth passes from day to night. Such is the anatomizing of twilight, so that when the sun is only 6 degrees below the horizon and dusk’s sky is the color of a robin’s egg we call it “civil twilight,” when it’s 12 degrees and the color of the wine-dark sea we refer to it as “nautical dusk,” and when it’s at it’s darkest before night’s blackness, dyed that color of perfect blue which is called “tekhelt” in biblical Hebrew, the color of the garment fringes for the High Priests dwelling in the Temple’s tabernacle, we call it “astronomical dusk.”

4.

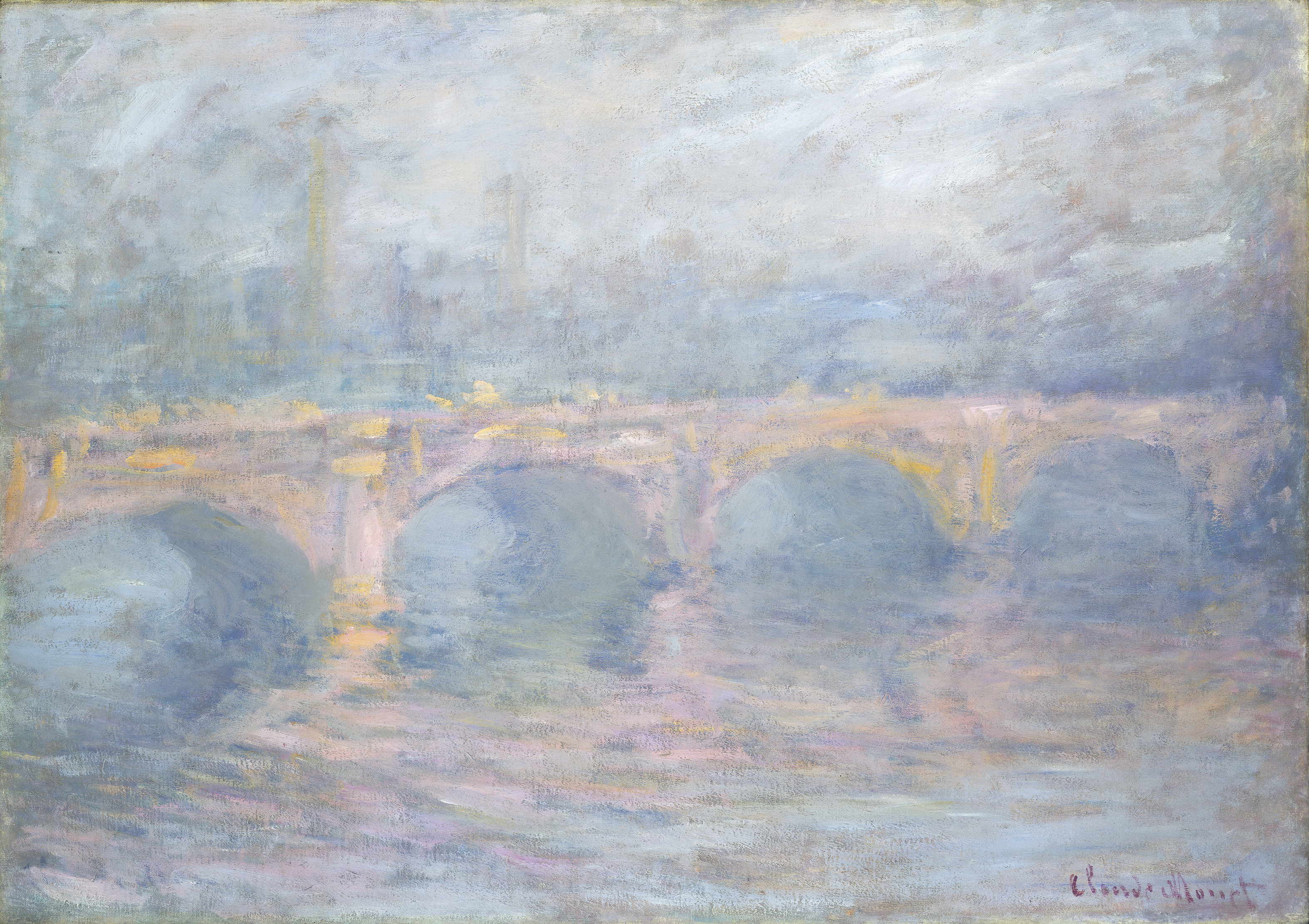

Painters are drawn to the golden hour, when solar light is evenly distributed and the Earth seems to softly glow. Claude Monet was particularly obsessed with how light diffuses through “particulate matter” (as Saha would put it). Monet explored shadow and sun as shifted across both seasons and hours. A striking portrayal of dusk is his 1904 Waterloo Bridge, London, at Sunset. In Monet’s painting, a hazy, blueish bridge disappears into abstraction. Particulars are subsumed into the melting glow of the polluted city at twilight, yet what luminescence refracts off said particulate matter! At twilight faces disappear, buildings and mountains become occluded, and the universe erases nature from our vision. Monet composed “a hymn to fleeting time,” as Carol Strickland explains in Impressionism: A Legacy of Light—an artistry whereby “One paints an impression of an hour of a day.” Monet calls forth that heavy hour, when in late summer there can be a stillness, and in many places (though not perhaps London) there is the intensity of insect shriek through the atmosphere.

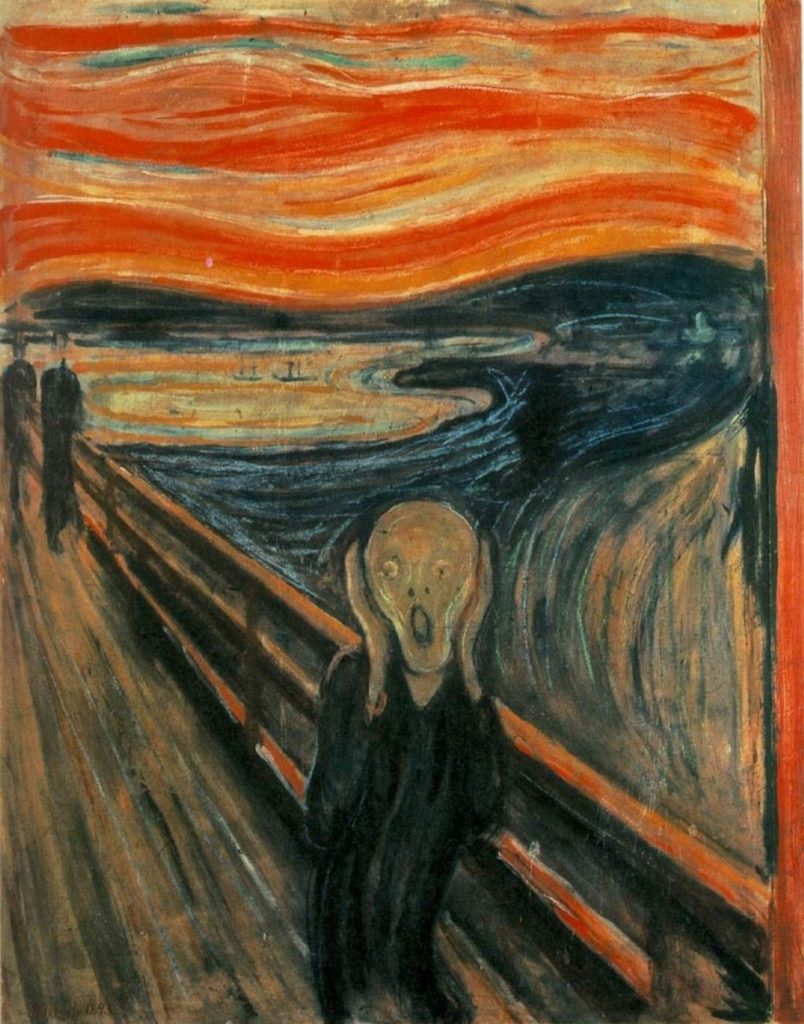

Monet’s younger contemporary Edvard Munch depicted a different persona of the dusk in his celebrated, copied, imitated, parodied painting The Scream. Composed in four different versions, Munch’s indelible image of a contorted, wavy, abstracted man on an Oslo bridge screaming in mask-like pantomime is replicated in dorm rooms posters and on countless kitschy museum gift shop objects, from neckties to pillows. The Scream captures not just the beauty of dusk, but the horror; not just the solar grandeur, but the intimations of extinction implicit in any good sunset. As his fellow melancholic Norwegian, the contemporary author Karl Ove Knausgaard, notes in his preface to the Gary Garrels- and Jon-Ove Steihaug-edited Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed, when viewing the works of Munch, one feels the need to exclaim “here was emotion, here was the abyss, here was the angst.” Knausgaard argues that even though “So much in our culture is rational,” we ultimately “have no words for the simplest of things,” including a fiery red sunset in late August. For Munch, the sky is nothing so much as coagulated blood coughed up into a sink.

Monet’s younger contemporary Edvard Munch depicted a different persona of the dusk in his celebrated, copied, imitated, parodied painting The Scream. Composed in four different versions, Munch’s indelible image of a contorted, wavy, abstracted man on an Oslo bridge screaming in mask-like pantomime is replicated in dorm rooms posters and on countless kitschy museum gift shop objects, from neckties to pillows. The Scream captures not just the beauty of dusk, but the horror; not just the solar grandeur, but the intimations of extinction implicit in any good sunset. As his fellow melancholic Norwegian, the contemporary author Karl Ove Knausgaard, notes in his preface to the Gary Garrels- and Jon-Ove Steihaug-edited Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed, when viewing the works of Munch, one feels the need to exclaim “here was emotion, here was the abyss, here was the angst.” Knausgaard argues that even though “So much in our culture is rational,” we ultimately “have no words for the simplest of things,” including a fiery red sunset in late August. For Munch, the sky is nothing so much as coagulated blood coughed up into a sink.

5.

5.

When considering sunsets, it’s hard not to invoke that old literary critical cliché of the symbol, even though that word has been largely verboten from serious academic literary theory for half a century. Yet the sunset can’t help seeming symbolic of something greater than itself, perhaps even to an overdetermined extent. Mather saw Armageddon, Kerouac felt intoxication, and Munch heard a scream. Sunsets with their clearly delineated endings are difficult not to interpret as the last act, the final curtain call, the epilogue, death. So saturated with meaning, that overreliance on the setting sun in a novel, or a film, or a television show can’t help seeming easy. Jean Chevalier, in his indispensable The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols, classified a number of concepts which the setting sun is used to represent. Of the direction of the setting sun, Chevalier writes that “West is the land of evening, of old age, of the descending passage of the Sun.”

In her meditation on the relative cultural semiotics of light and shadow, The Millions staff writer Jianan Qian elucidates how a sunset is never just one thing, arguing that in classical Chinese poetry there is a melancholy about dusk, while in western poets from Carl Sandburg to Gustave Flaubert the hour is imbued with a sense of hopefulness. She asks, “Can we reserve a little space for our own, where we worship our shadows, not your light?” The great power of the sunset, as I see it, is in that marriage of both shadow and light. From Gilgamesh to Cormac McCarthy, west has been the direction where the sun rests and light is extinguished, the inevitable location of death. We see ecstatic vision of that blood-red sphere, like the ripe yolk of some cracked egg sinking downward into the bowl of the western horizon. A symbol can be a fallacious thing, however, especially as we justify our belief in the Westerly Kingdom of Death, as a sunset is of course nothing but an optic trick. Like the Flaming Lips sang on 2002’s Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, “You realize the sun doesn’t go down / It’s just an illusion caused by the world spinning round.” A sunset is finally nothing more than itself.

In her meditation on the relative cultural semiotics of light and shadow, The Millions staff writer Jianan Qian elucidates how a sunset is never just one thing, arguing that in classical Chinese poetry there is a melancholy about dusk, while in western poets from Carl Sandburg to Gustave Flaubert the hour is imbued with a sense of hopefulness. She asks, “Can we reserve a little space for our own, where we worship our shadows, not your light?” The great power of the sunset, as I see it, is in that marriage of both shadow and light. From Gilgamesh to Cormac McCarthy, west has been the direction where the sun rests and light is extinguished, the inevitable location of death. We see ecstatic vision of that blood-red sphere, like the ripe yolk of some cracked egg sinking downward into the bowl of the western horizon. A symbol can be a fallacious thing, however, especially as we justify our belief in the Westerly Kingdom of Death, as a sunset is of course nothing but an optic trick. Like the Flaming Lips sang on 2002’s Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots, “You realize the sun doesn’t go down / It’s just an illusion caused by the world spinning round.” A sunset is finally nothing more than itself.

6.

6.

Humanity’s understanding of this illusion exemplifies the new rationality—of humanity’s rejection of symbol in favor of measurable phenomenon. Anticipating the Oklahoma-based rock band by a good five centuries, the man who would give his name to the accurate model of the solar system would write that “since the sun remains stationary, whatever appears as a motion of the sun is really due rather to the motion of the earth.” Heliocentrism predates Copernicus’s 1543 On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres, but it was that Polish monk who would lend those models his name, his hypothesis later confirmed by Galileo Galilei, forever demolishing vestiges of the geocentric Ptolemaic model. Copernicus based his conclusion on a more parsimonious mathematics, eliminating the baroque system of epicycles that was previously required to explain anomalous celestial movements. In Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud, Peter Watson explains that the “traditional way to explain the heavens was in disarray,” so that the great genius of Copernicus was to simplify those models, even as in the process our exulted stature in creation would be displaced. Humanity was no longer at the center of reality, for the abolishment of the sunset was as if the abolishment of our significance.

Novelist and journalist William T. Vollmann, in his incredibly unlikely Uncentering the Earth: Copernicus and The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, wrote that “What moves me the most about [Copernicus]” was his struggle to “free the human mind from a false system.” Famed Russian dissident and dystopian novelist Arthur Koestler didn’t completely agree; in his classic The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe, he opined that “man’s destiny was no longer determined from ‘above’” but rather from “‘below’ by … sub-human agencies.” These things could determine our fate but “provide … no moral guidance, no values and meaning.” Koestler was not such a relativist that he’d deny the accuracy of Copernicus’s verified hypothesis; rather, he chose to acknowledge that sometimes mythos undeniably holds an appeal that can’t be exorcised by data.

Novelist and journalist William T. Vollmann, in his incredibly unlikely Uncentering the Earth: Copernicus and The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, wrote that “What moves me the most about [Copernicus]” was his struggle to “free the human mind from a false system.” Famed Russian dissident and dystopian novelist Arthur Koestler didn’t completely agree; in his classic The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe, he opined that “man’s destiny was no longer determined from ‘above’” but rather from “‘below’ by … sub-human agencies.” These things could determine our fate but “provide … no moral guidance, no values and meaning.” Koestler was not such a relativist that he’d deny the accuracy of Copernicus’s verified hypothesis; rather, he chose to acknowledge that sometimes mythos undeniably holds an appeal that can’t be exorcised by data.

7.

7.

Karen Armstrong writes in A Short History of Myth that “We are meaning-seeking creatures.” Armstrong, like Koestler, wouldn’t dispute Copernicus’s conclusions, but she would claim that it’s a category mistake to abandon myth simply because it isn’t literally true. She explains that mythology has never been primitive science or empiricism done poorly. Logos and mythos, Armstrong argues, are two different epistemologies; the former is concerned with what’s factual, the latter with what’s true. Myths can’t calculate the parabola of a satellite, they can’t sequence the human genome or program a computer. But Armstrong argues that it’s a positivist error to collapse mythos into logos, for myth is concerned not with explanation but with meaning.

That the sun should be so present across myths is not surprising; even in our contemporary era there is something mysterious about a sunset. A preponderance of sun gods: Egypt had Amun-Ra; Greece and Rome had Apollo. During the Amarna Dynasty, Pharaoh Amenhotep IV discovered monotheism and rechristened himself Akhenaten, abolishing the pantheon in favor of the singular Aten, god of the sun. The “Hymn to Aten,” whose language was later echoed in the Psalms, chants toward its subject that “When you have arisen, they live, / When you set, they die / You yourself are lifetime and men live in you,” transfiguring all of existence by the cycle of the sunset. Rosalie David in Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt explains that the pharaoh had “embarked on a course of action which has been … interpreted as a ‘religious revolution,’” whereby this imposed “form of solar monotheism” was defined by the “creative energy of the sun.”

That the sun should be so present across myths is not surprising; even in our contemporary era there is something mysterious about a sunset. A preponderance of sun gods: Egypt had Amun-Ra; Greece and Rome had Apollo. During the Amarna Dynasty, Pharaoh Amenhotep IV discovered monotheism and rechristened himself Akhenaten, abolishing the pantheon in favor of the singular Aten, god of the sun. The “Hymn to Aten,” whose language was later echoed in the Psalms, chants toward its subject that “When you have arisen, they live, / When you set, they die / You yourself are lifetime and men live in you,” transfiguring all of existence by the cycle of the sunset. Rosalie David in Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt explains that the pharaoh had “embarked on a course of action which has been … interpreted as a ‘religious revolution,’” whereby this imposed “form of solar monotheism” was defined by the “creative energy of the sun.”

With the changing of a single letter, Christians also worship the Son. After all, Psalm 84:11 reads, “The Lord God is a sun,” with all of the implications of death and resurrection that that endless cycle of dusk and dawn represent. David writes of how the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead drew “parallel between the sun’s passage from night to day, and the deceased’s emergence from the tomb to the daylight”—Pagan wisdom, for in the transit of orb there is a narrative of death and renewal told daily, as sure as Apollo or Sol Invictus led their chariots across the dome of the Earth. As logos, all such stories are literally untrue, but that’s the least interesting thing about them. Such stories aren’t cosmology, but what they tell us is that though the sun sets, it will rise again, with all that that formulation implies.

With the changing of a single letter, Christians also worship the Son. After all, Psalm 84:11 reads, “The Lord God is a sun,” with all of the implications of death and resurrection that that endless cycle of dusk and dawn represent. David writes of how the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead drew “parallel between the sun’s passage from night to day, and the deceased’s emergence from the tomb to the daylight”—Pagan wisdom, for in the transit of orb there is a narrative of death and renewal told daily, as sure as Apollo or Sol Invictus led their chariots across the dome of the Earth. As logos, all such stories are literally untrue, but that’s the least interesting thing about them. Such stories aren’t cosmology, but what they tell us is that though the sun sets, it will rise again, with all that that formulation implies.

In his 1957 classic Mythologies, Roland Barthes writes that “Myth is neither a lie nor a confession: it is an inflexion.” At a frequency too high-pitched for most of us to hear, the sun god’s chariot still passes in transit from east to west. Laugh if we must at the strange contingencies of myth, but such narratives order our lives. When Mather looked westward across the massive expanse of that Hesperian continent where he imagined God’s Kingdom would one day dwell, could he have possibly imagined that at the terminus of this land there would be an empire of a different sort, devoted to the production of fantasy, albeit written in celluloid rather than mythos, in a place where Apollo’s chariot lands each dusk, and that we’ve elected to call Sunset Boulevard?

In his 1957 classic Mythologies, Roland Barthes writes that “Myth is neither a lie nor a confession: it is an inflexion.” At a frequency too high-pitched for most of us to hear, the sun god’s chariot still passes in transit from east to west. Laugh if we must at the strange contingencies of myth, but such narratives order our lives. When Mather looked westward across the massive expanse of that Hesperian continent where he imagined God’s Kingdom would one day dwell, could he have possibly imagined that at the terminus of this land there would be an empire of a different sort, devoted to the production of fantasy, albeit written in celluloid rather than mythos, in a place where Apollo’s chariot lands each dusk, and that we’ve elected to call Sunset Boulevard?

8.

8.

For most of human history, sunset meant something dangerous and intractable—the approach of darkness. In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, A. Roger Ekirch writes that before the electric lights, the “darkness of night appears palpable. Evening does not arrive; it ‘thickens.’” Sunsets may be beautiful, but they bring “Night … man’s first necessary evil, our oldest and most haunting terror.” Camping can perhaps trick the city dweller into a simulation of that all-encompassing darkness from before the Industrial Revolution, but it’s a world that’s fundamentally inaccessible to us. Ekirch explains how “All forms of artificial illumination—not just lamps but torches and candles—helped early on to alleviate nocturnal anxieties,” yet even the brightest of candles flickers lower than the dullest of flashlights. This was an era where “bizarre sight and queer sounds” would come and vanish, a dark kingdom of the hours where “‘Night … belongs to the spirits.’” Perilous night, the totalizing regime of nocturnal darkness, would soon be banished. Artificial illumination steadily improved throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, with the mass production of candles, the introduction of burning coal, and the standardization of both oil and gas lamps.

What would ultimately destroy those old gods was the birth of new ones, or as Ernest Freeberg writes, such was the awe generated by a “light that could burn without spark and smoke … [which] promised to turn vast swaths of night into day.” In his account The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America, Freeberg explains that the invention of the electric light bulb was “rightly hailed as a ‘marvel’ and a milestone in human history.” Millennia of people had been terrified by the sun’s descent, fearful of whatever creature swallowed that disk every night. And in a bright, glowing second of filament, the darkness could be forever slain with a light bulb. Deicide by technology, for Aten and Apollo’s fickleness were ultimately tamed by Thomas Edison.

What would ultimately destroy those old gods was the birth of new ones, or as Ernest Freeberg writes, such was the awe generated by a “light that could burn without spark and smoke … [which] promised to turn vast swaths of night into day.” In his account The Age of Edison: Electric Light and the Invention of Modern America, Freeberg explains that the invention of the electric light bulb was “rightly hailed as a ‘marvel’ and a milestone in human history.” Millennia of people had been terrified by the sun’s descent, fearful of whatever creature swallowed that disk every night. And in a bright, glowing second of filament, the darkness could be forever slain with a light bulb. Deicide by technology, for Aten and Apollo’s fickleness were ultimately tamed by Thomas Edison.

9.

We may have abolished one master, but as Ekirch explains, so, too, was lost “a distinct culture, with many of its own customs and rituals.” Electricity has facilitated the never-ending thrum of commerce that defines modernity, so darkness may have been eradicated, but it’s been replaced with the tyranny of neon activity. Servant to such a master as this, there is something countercultural in reinvesting the sunset with its significance, in seeing it as that portal which shepherds us into the province of night, with all of those attendant differences.

Imbued with more meaning than its Christian descendant, the Jewish Sabbath is ideally a temporal utopia, a respite from the gods of this profane world. Measured from Friday dusk to that of Saturday, Sabbath represents a re-enchantment of the sunset. Anthropologist and physician Melvin Konner writes in Unsettled: An Anthropology of the Jews that the “Friday evening dusk was greeted as an arriving queen,” while the “Sabbath’s departure at dusk was marked with the rite of … separation.” Herbert Weiner in Nine and a Half Mystics: The Kabbala Today explicates the mystical symbolism of the “palace of the Sabbath,” writing that the period of time from dusk to dusk marks the “annulment of those divisions which characterize ordinary existence—between man and man, between mind and heart, idea and reality.” Dusk’s arrival abolishes our fallen world—at least for a day.

Imbued with more meaning than its Christian descendant, the Jewish Sabbath is ideally a temporal utopia, a respite from the gods of this profane world. Measured from Friday dusk to that of Saturday, Sabbath represents a re-enchantment of the sunset. Anthropologist and physician Melvin Konner writes in Unsettled: An Anthropology of the Jews that the “Friday evening dusk was greeted as an arriving queen,” while the “Sabbath’s departure at dusk was marked with the rite of … separation.” Herbert Weiner in Nine and a Half Mystics: The Kabbala Today explicates the mystical symbolism of the “palace of the Sabbath,” writing that the period of time from dusk to dusk marks the “annulment of those divisions which characterize ordinary existence—between man and man, between mind and heart, idea and reality.” Dusk’s arrival abolishes our fallen world—at least for a day.

The medieval Sephardic rabbi Avraham Abulafia writes in his poem “The Book of the Letter,” included in the Peter Cole-edited anthology The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492, that the “Sabbath subdues all the days of the week,” or as I might put it: “Everybody’s working for the weekend.” That’s what it felt like when I was in high school, and my friends and I began to make a ritual of ending the week at a local hoagie shop in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill, where in imitation of back-slapping old men we’d shake hands and genuinely wish each other a “Gut Shabbes,” ironically over cheesesteaks. Walking home in December, reflecting on a tradition not my own, I would have opportunity to observe the early dusk through the low winter sun; the way that the orange, lolling fingers of light rippled over cloudy, compacted gauze, and sometimes in moments of youthful exuberance I thought that I felt what Konner describes as the “consistency of the Sabbath… [its] seeming taste of heaven.”

The medieval Sephardic rabbi Avraham Abulafia writes in his poem “The Book of the Letter,” included in the Peter Cole-edited anthology The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492, that the “Sabbath subdues all the days of the week,” or as I might put it: “Everybody’s working for the weekend.” That’s what it felt like when I was in high school, and my friends and I began to make a ritual of ending the week at a local hoagie shop in Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill, where in imitation of back-slapping old men we’d shake hands and genuinely wish each other a “Gut Shabbes,” ironically over cheesesteaks. Walking home in December, reflecting on a tradition not my own, I would have opportunity to observe the early dusk through the low winter sun; the way that the orange, lolling fingers of light rippled over cloudy, compacted gauze, and sometimes in moments of youthful exuberance I thought that I felt what Konner describes as the “consistency of the Sabbath… [its] seeming taste of heaven.”

10.

There are the Pittsburgh sunsets from when I was growing up, when the red sky could burst from the low threading of hazy greyness, light refracted from both drizzle and the particulate pumped into the atmosphere from the massive coke processing plant south of the city, the dramatic hurried rush of orange collapse as the sun sank below the unfairly gorgeous hilly skyline, looking like it had been planned by a sacred conspiracy of divinities.

Or, leaving by ferry from Hiroshima and approaching the stolid, painted red wood of the torii gate marking the entrance to the Itsukushima shrine, which seems to float on the water off of Miyajima Island, dedicated to the brother of Amaterasu, appropriately enough the sun goddess. This is the sort of dusk described by the 17th-century poet Matsuo Basho as encompassing the “twilight rain / these brilliant hued / hibiscus… / A lovely sunset,” where that beatific arch seems to connect the ocean to the sky as the fiery sun descends into the sea behind a fringe of green mountains on the distant main island—so beautiful that it seems incorrect.

Or, the pyrotechnic psychedelia of the massive sun burrowing into the Pacific Ocean off of Waikiki Beach, a sunset which reminds you that there is something like outer space about the sea, a performance of your personal, immaculate insignificance in the presence of something that absurdly glowing. Hawaii’s sunsets are appropriately described by Sarah Vowel in Unfamiliar Fishes as “lurid.” As is twilight on that other ocean, watching the sun’s vital hemorrhage on a beach in Curaçao, looking like Derek Walcott’s description of the Caribbean as being where “the sunset bleeds like a cut wrist.”

Or, the pyrotechnic psychedelia of the massive sun burrowing into the Pacific Ocean off of Waikiki Beach, a sunset which reminds you that there is something like outer space about the sea, a performance of your personal, immaculate insignificance in the presence of something that absurdly glowing. Hawaii’s sunsets are appropriately described by Sarah Vowel in Unfamiliar Fishes as “lurid.” As is twilight on that other ocean, watching the sun’s vital hemorrhage on a beach in Curaçao, looking like Derek Walcott’s description of the Caribbean as being where “the sunset bleeds like a cut wrist.”

Or, the fragrant still of Central Park at dusk, when New York City is quiet enough, for just a second, that it charms you, air threaded with the warm charge of late summer, when that rectangular garden at the center of Manhattan allows you to contemplate such green thought in a green shade. Over the Hudson and New Jersey, the sun drops into that western home of the rest of the New World, and for a bit of the golden hour all of the light is refracted off of the glass, steel, and stone of Central Park West, the skyscrapers acting as prisms and mirrors for the sun, reflected a thousand times over in the windows of women and men.

Or, the raspberry-tangerine sherbet skies of an early autumn dusk over the outfield wall of a minor league baseball stadium in eastern Pennsylvania; the increasingly quicker nightfall of the season now interrupting earlier innings. Crackle over the diamond as the temperature drops, and the lights on the scoreboard now so bright they hurt your eyes. In A Great and Glorious Game: Baseball Writings, A. Bartlett Giamatti writes that the purpose of baseball in the fall is precisely that “It is designed to break your heart … when the days are all twilight.”

Or, the raspberry-tangerine sherbet skies of an early autumn dusk over the outfield wall of a minor league baseball stadium in eastern Pennsylvania; the increasingly quicker nightfall of the season now interrupting earlier innings. Crackle over the diamond as the temperature drops, and the lights on the scoreboard now so bright they hurt your eyes. In A Great and Glorious Game: Baseball Writings, A. Bartlett Giamatti writes that the purpose of baseball in the fall is precisely that “It is designed to break your heart … when the days are all twilight.”

And of course, facing west from the Glasgow Necropolis, scattered with monuments to textile factory owners and brewers, looking out over the dense, crooked labyrinth of that grey city, a misty Scottish sun lolling towards the horizon, where she shines off of the broken windows of faraway tenement high rises. This sunset, this smear of yellow and orange, this eruption of blue and red, giving off final light as if it were God’s fireworks display, standing in a cemetery and realizing what sunsets have always really meant. Emily Dickinson understood dusk’s indomitable logic when she wrote that “We passed the Setting Sun – / Or rather – He passed Us,” where her and her traveling companion are headed west “toward Eternity.”

11.

Dusk is nature’s enjambment. In the midst of the muggy Anthropocene, when humanity has seemingly wrenched the very seasons out of their proper order, with Antarctic ice-shelfs collapsing and river banks receding in drought while revealing the marked warning stones left from those in the lean times of famines past, dusk provides us a talisman reminding us that even we have our limits. In the filtered, gloaming light of an irreversible sunset there is profound wisdom, the experience of finality and the understanding that “This, too, shall pass.” Dusk reminds us that we’re not in control, not even of our extinctions. The poetics of sunset speaks of endings and closings, apocalypses and death. The hour before evening is not just the most contemplative one of a day’s existence, but the most poetic as well. Drawing a close to the light which illuminated before into the promises of darkness. Sunset is the most beautiful hour.