1.

On impulse, before anything else, in a white E350 Ford van I drive into Mauritania at sunset. I see a duneland, and then houses built as if to imitate matchboxes. Today Eid ul-Fitr begins. Men are walking back from mosques, women and children trailing them, sure-footed and celebratory. I see all this with my nose pressed to the window. The men wear long, loose-fitting garments, mostly white, sometimes light blue. I watch them from behind, and think of the word swashbuckle. I am moved by these swaggering bodies, dressed in their finest, walking to houses that look only seven feet high. I envy the ardor in their gait, a lack of hurry, as if by walking they possess a piece of the earth.

I want to be these men.

2.

Awake or in a dream, faces and images and gestures from my travels return to me in great detail. Sometimes it is the wind, sputtering against the window of the car I am in. Or an underfed dog, rummaging through rubbish for a glinting bone. Or a boat unmanned in the middle of a river, seen from afar.

I began to exchange emails with a relative who requested anonymity. My first email was a list of all the towns I had slept in during my travels, at least for a night. Towns in which I turned in my sleep unsure of where I was, whether I was bathed in sweat or in tears, or if I lay beside a lover or a travel companion. I hoped, I wrote, that the cities appeared untethered to their countries—an atlas of a borderless world. In the first response I received, I was urged to recount stories of strange sightings, emotions, and encounters, remembered or imagined.

Take me with you on your journeys, my relative replied.

Let me go in your place.

3.

Once, I arrived at a bus station in Lome 10 minutes past departure time. The buses headed for Accra left every two hours. An agent advised me to purchase a new ticket. An arts centre had taken great pains to create and maintain a schedule for my West African book tour. I spoke little French and had no working phone to explain the predicament to my hosts. In my attempt to salvage the situation, I walked up to a few strangers in the terminus. I asked if I could borrow their phones, and for a few seconds each would listen, confused at the meaning of my French, which was little more than gestures and babbles. Then, when understanding came, they would shake their head in the negative, making one excuse or the other.

The physical details of that Lome terminus skip my mind, but I do not forget the heads of potential benefactors shaking in the negative. Hadn’t I deserved this turn of events? That morning, before taking a shower, I sought familiarity with the streets around my hotel. I took photographs of walls, gates, and passageways, passing time. Facing one of those walls, I attempted to make sense of the notice: “vendre,” a word for sale; “ne pas,” a sense of disallowance. Beyond the wall, life seemed unrestrained, yet the inscription seemed to warn against crossing over. If the people moving on the other side were tall enough I saw their heads, nodding in conversation, turning in dissent, steadied in motion.

4.

I travel under the evening cloud, an ochre sky. The first word I regard is “marché.” I see a vulcanizer’s pile of discarded tires beside the kiosk and imagine the word suggests anything but a small market. It is here, my first time outside Nigeria—on the dusty road leading outside Kouserri, 25 kilometers from N’djamena—that I learn I have crossed into the other side of the language border. If I could show my face, it would indicate the creases and frowns of a mute observer.

5.

For days, depending on the availability of Mamadou, I had no guide in Dakar. It amuses me, now that I remember, how I walked in Point E nervous of what world was possible without English words. My French and Wolof constituted no more than a sentence when combined.

Once, overlooking the sea in Ngor, my eyes followed the path the surfers made as they performed their stunts. I see what rivers—the Nile in its stretch beyond the Mediterranean, the Niger as it joins Timbuktu to Lokoja—teach with their flowing mass. Wave falls on wave, as one dialect inflects on another. All rivers are multilingual.

I was nothing without the translators to whom my questions were entrusted, whether in Bamako, Abidjan, or Casablanca. But, alone, as was often the case, I wondered how to survive without them.

6.

I looked at French words to guess their meanings. But there were times I faked understanding. In Rabat, when I went to Pause Gourmet for salad and café au lait, I would say yes to everything, hoping the question posed required a yes or a no. All my yeses were indicative of a larger paranoia, that of being marked as a clueless stranger. What the hell was a person who didn’t speak French or Arabic doing in Morocco? Sometimes yes would be inappropriate, or insufficient, requiring a modification. The waitress would immediately perceive my limited understanding, and ask for what I wanted in a clearer, drawn-out way. Again, I’d nod, suggesting finality with a smile. That would settle things.

Or when Khadija rang the bell of my apartment. I got dressed and went for the door. She was mopping the floor, this middle-aged woman who began to speak in rapid French when I appeared. I perceived she was talking about her work in the building—travail, ici. My nods were tentative, speculative. She didn’t seem to mind. She wanted to exchange numbers. If I wanted any help with the apartment I could call her. She left and returned with her number on a small piece of paper, written in blue ink. Also, a small piece of paper for me to write mine. When I gave her my number she asked if it was okay for her to call me. Oui, oui.

Or when a man came from the hotel to take me to a new apartment. The agreement was for me to stay in the first apartment until the new one was ready. He came to take my bags, explaining this with limited French. Frustrated by our translation problems, he asked if I spoke Arabic. No. From then on he seemed impatient, and yet subdued—almost rash in the way he suggested what he meant by lifting things and moving them before attempting to communicate where we were going.

After regular visits to Pizza Zoom for lunch and dinner, it seemed I was marked alien. I perceived—perhaps by dint of exaggerated self-importance—that I was the subject of fleeting discussions in the kitchen. Waitresses and their male colleagues recounted their encounters with me: He nods to everything, he wouldn’t pronounce “brochette” the right way, he always reads an English book. English is my fate here. The cashier, once when I tried to pay for my meal, switched to English to confirm what I’d had. I responded with relief. At last.

I wore my language deficiency like a veneer, like gauze, like stratum. Underneath was tangible communication, out of reach. Yet I did not bemoan this. My deficiency was benign in comparison. For migrants arriving in Morocco from countries south of the Sahara who have to make a living or wait almost interminably for a better life, to acculturate is to survive. Without the knowledge of French or Moroccan Arabic, they face the belligerent wall of inadmissibility, confined to the fringes of their new society.

7.

The cost of my travels, if I made a tentative sum, included a precarious love affair in Lagos. I gathered memorabilia in each new city, as if they were placatory bricks to bridge the distance; paid passage from her to me. Those potential keepsakes had the feel of poems written on the spur of sentiment, for immediate effect: petals of a sunflower carved on a wooden brooch; a key ring with the depiction of a local Marabou; baking instructions behind a postcard. On two other postcards, covered in doodles, I wrote the following:

I practice what kind of shapes I’ll make on your body:

Clusters of circles on the back of your wrists…

Repeated triangles around your navel…

Spheres with my lips on the corners of your face, then your mouth…

A rhombus around the scar on your left arm…

Numerous inch-wide rectangles from your knee to your hip…

Squares with curved edges along your torso.

For the sake of this exercise, I have bought a sketchbook.

When will I see you again?

I’ve made my days into dispatches and unsent letters. I sleep little. I switch beds, and night after night hope is gathered in sacks of the unknown.

8.

Once in N’djamena, whilst in a market, I walked with a small camera. In the course of my strolls, I refrained from taking photographs. Sometimes I made exceptions, depending on what was in view. The market in N’djamena was the first place where I saw the head and entrails of a vulture being sold. For voodoo, I was told.

A woman in hijab held a weeping man, patting his head, wiping his face, their legs sprawled on the dusty ground. I approached, uncertain. When I realized I had caught the attention of the woman, who had managed to calm the man a bit, I held up the camera for a shot. The woman’s sudden scream jolted the man, and he became inconsolable, again. I grew nervous when I noticed people pointing, encircling me. A policeman appeared—I might have been watched, or, worse, followed. The policeman pointed to the camera. I handed it to him without protest. He led me to a station I hadn’t noticed before, about 50 yards behind where the weeping man lay.

I was released six hours later following the intervention of an hotelier I met on my first night in Chad. The photograph had been deleted. I walked back to the market, to make my way out. The woman in hijab still comforted the weeping man, who, in addition to being inconsolable, now threw dust, from time to time, at people walking past.

9.

Most mornings in Nouakchott I sit with Lejam to eat. For breakfast we pay a total of 1,000 ouguiya for baguette and egg, juice and butter, café au lait, and water. It takes me 10 minutes to walk to the restaurant. For 10 minutes I walk with music, Sony earphones around my head, a notebook in my pocket. I walk, wearing the slippers I had bought in Dakar. Sand flies in every direction. Desert sand. Despite its modernization, writes a visitor, Nouakchott still seems like an encampment of nomads.

Lejam, one of the nine artists I’m traveling with, takes pictures of me. He does this as if he has his finger and eyes on moments of significance—like the photograph he takes in Rosso, the town with a river that separates Senegal from Mauritania, right at the moment we enter the ferry. And it is after one of those breakfasts that I go with him to a visa preparation office, which bore “Formalite Visa—Maroc-Espagne-France” above it. White Mauritanians oversee would-be applicants as they gather required documents. Many of these applicants will fail to get visas. They will risk deportation and the harshness of the sea, and immigration officials armed by the European Union. I do not enter the visa preparation office.

The conversation about preparing documents to apply for a Moroccan visa have been left to E., the director of the organization undertaking the road trip. He is fluent in French. The trip, expected to last a total of 150 days, is a stretch from Lagos to Sarajevo. Mauritania is the last frontier before Morocco, and Morocco is the last frontier before Spain. Six persons in my group require Moroccan visas. In the months before now, E. and I have attempted several applications for the Moroccan visa—in Abuja, Bamako and Dakar—without success. Each consulate, in turn, referred to an earlier intolerable mistake: We had included “Western Sahara” in our itinerary as an independent country, ignorant of Morocco’s claim to control its territory, its people, and its resources.

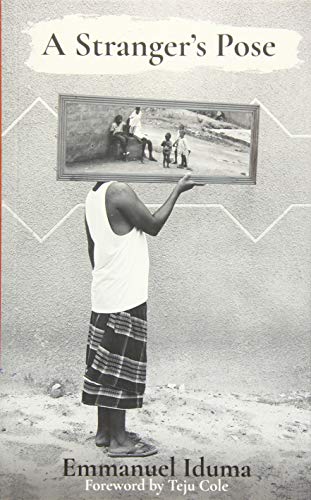

Now Lejam, who owns a Canadian passport and doesn’t need a visa, takes a photograph of me with his phone. I pose beside the office door, my eyes half-opened. But my face, when I consider the photograph later, indicates I am aware of how I position myself. Lejam asks me to stand beside the door after he has seen how E. stands—his stance more or less an indication of tenseness, as if readying to spring back into the office. My pose camouflages this tenseness, even nullifies it. I rest my back on the wall, standing in a way that suggests that if a chair were placed behind me, I would have slouched. I appear carefree, as one deferring worry.

Asked by Lejam to pose beside a tense E., I wonder about how, on certain occasions, in the course of travels in which nothing is certain, to pose for a photograph is to acknowledge the possibility of respite.

E. is a good dancer, so good that when we go to parties people stop to watch him, even making videos with their phones. In Nouakchott, Lejam downloaded a number of Nigerian pop songs from iTunes, and when the day had come to an end, after another unsuccessful visa attempt, he would sometimes play the same songs back to back. E. and I would begin dancing, my moves hoping to imitate his. In that moment, being without a visa becomes a minor, distant worry. The only thing that would matter while we danced, like in the photograph, would be the here and now. How the body dancing, finds reprieve.

10.

On the night I arrive in Benin City I sit in a taxi. I am calmed by the driver’s chattiness. He describes the city’s quarters as we drive along. We are headed towards the G.R.A., and we drive past a hotel. It is lit with a floodlight, famous at night for men looking for sex. In front of the hotel there are taxis waiting. Even with a brief glance at the taxi drivers who loiter to pick up other men, I see that each is prepared for a long stay into the night. Perhaps they arrived early to claim spots. Or, tempted by what their eyes imagine their pockets can afford, they’ll make an offer to one of the women.

I do not see any woman waiting to be picked. It might be too early for this. It is only 8 p.m. How interesting, I think later, that there are men around the hotel for whom, like sex workers, this isn’t merely a question of pleasure. For both, the body is put to relentless work.

I ask the taxi driver for his number. Responding to impulse, I want him to take me around the city at daylight. He has lived all his life in Benin. Men like him carry routes within themselves. As though with each shortcut he takes, he sketches a less officious map of the city. I want to assimilate, in the shortest time possible, the knowledge of all the routes he favors, the city mapped by his hand.

He recites his number to me, confirming he could drive me at daylight. But the next day, and the day after that, I forget to call him.

Excerpted from A Stranger’s Pose by Emmanuel Iduma. Published with permission from Cassava Republic Press. All Rights Reserved.