Wandering the aisles made of beige steel and unrememberable carpet that was the poetry section of my local suburban library, I waited for poetry to come to me. What arrived was The Painted Bed, a collection by Donald Hall. I could’ve opened it to any poem. The title poem. “After Three Years” or “Kill the Day,” maybe. It was an unraveling, the first time I had witnessed language bearing the pain that lives in the wake of immense loss with such incisive vulnerability. I checked it out and consumed the whole thing immediately. I was 17.

A decade away from that moment, Donald Hall is now dead. The event that consumed so much of his writing has now arrived for him. From the earliest poems—the ones written during his first marriage and the years spent teaching before his second, great marriage to the poet Jane Kenyon—it was a nagging subject. Death haunted his poems from his returning to the ancestral farm with Kenyon, a purposeful separation from the world of the academy, through his long and happy hermitage until his diagnosis with cancer, which he survived, and then Kenyon’s diagnosis with leukemia, which she did not. The poems after that, until Hall turned 80 and decided he no longer had the capacity for poetry, are absolutely steeped in it.

Saying that Hall was some kind of apostle of grief is to mischaracterize him, though. There were many Donald Halls. There was the early Hall, first poetry editor of The Paris Review and poetry anthologizer of particular staunchness who ensured the ongoing legacy of the greats who stood just behind him like T.S. Eliot and Robert Frost. In his early years, Hall wanted to impose his taste upon the poetry world at large, fiercely advocating for contemporary poetry, with a particular fondness for poets like Geoffrey Hill and Thom Gunn, even as writers outside of the nation’s universities were creating poetry in their own image.

Saying that Hall was some kind of apostle of grief is to mischaracterize him, though. There were many Donald Halls. There was the early Hall, first poetry editor of The Paris Review and poetry anthologizer of particular staunchness who ensured the ongoing legacy of the greats who stood just behind him like T.S. Eliot and Robert Frost. In his early years, Hall wanted to impose his taste upon the poetry world at large, fiercely advocating for contemporary poetry, with a particular fondness for poets like Geoffrey Hill and Thom Gunn, even as writers outside of the nation’s universities were creating poetry in their own image.

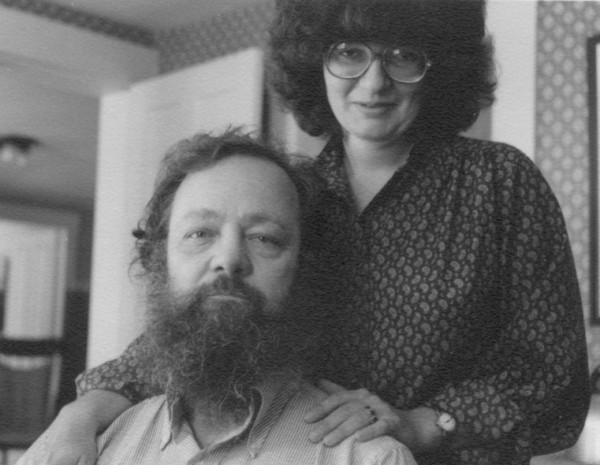

There was the Donald Hall that left the world of higher education to wholly dedicate himself to his ancestral New Hampshire farm, where his attention was upon the daily devotion to his now-hallowed relationship with Jane Kenyon and his writing. Though present throughout his early poetry, the focus of his writing sharpened onto themes of grief, lingering and ever-present in the ghostly shadow of Mount Kearsarge—a place where the spirits of the past seemed to mingle with the heat of the living, and desire, as the long-blooming flower of Hall’s deep affection for Kenyon grew along with her own career as a poet as it eventually eclipsed his own.

Then there was Donald Hall, alone. The final third of his career was almost entirely defined by absence. His own miraculous cancer survival moved nearly immediately into Kenyon’s leukemia diagnosis, her dying, and her death. The elegiac qualities moved from the tinged shadows of his work and onto the main stage, consuming it as he chronicled the slow descent into the valley of a Jane-less life and his long wait there.

The other Donald Halls—the baseball writer, the poet laureate, the endless correspondent—revolved in peripheral moons around the great preoccupations of his life. It’s tempting, at the end of his long life, to simply take the memory of Hall and quietly place him in the corral labeled “Pastoral Poets.” In the wake of his death, many have eulogized him while confining him there. Though Ted Kooser and Wendell Berry may have some shared images with him, Hall’s writing on his roots, the landscape of New Hampshire, and the people who populate his world were much darker and deeper, much stranger than what can simply and neatly be patted on the head and deemed pastoral meditation. His writing is much more aptly compared to his forebear, T.S. Eliot, or the fellow native New England poet Elizabeth Bishop than to his rural contemporaries.

What makes Donald Hall a remarkable poet, what assures him a lasting place in an American literature that looks much different from when he began to edit The Paris Review or his purposeful anthologies, was his dedication to honesty. This sounds banal to state, but to read Hall, from the very beginning right up until the end, is to watch a writer grow into a kind of honest and forthright form. The way Hall laid bare and excavated the guts of humanity, ripping wide open the tepid surface of the most conservative annexes of society to reveal how it all dripped with raging grief and aching desire was, and remains, profound. As a writer, he seemed to really take to heart the words the sculptor Henry Moore once said to him, quoting Rodin as he quoted a craftsman: “Never think of a surface except as the extension of a volume.”

An important part of his dedication to honesty was that it demanded humor, and Hall’s was wry and midnight dark. In the poem “Letter with No Address,” one of his many odes to life after Kenyon’s death, he describes yet another day of crushing grief, and he ends on this image: “Sometimes, coming back home / to our circular driveway, / I imagine you’ve returned / before me, bags of groceries upright / in the back of the Saab, / its trunk lid delicately raised / as if proposing an encounter, / dog-fashion, with the Honda.” Hall was a master at this, disorienting an entire poem to crushing ends with apparent glee, but to a purposeful end. As he says in another poem nearby: “Lust is grief / that has turned over in bed / to look the other way.”

Donald Hall is now, after it all, the posthumous Donald Hall. He is now the deceased Donald Hall, as he so looked forward to being in many poems. He’s now, if not with his beloved Jane Kenyon, at least no longer in a world without her. Only the words they wrote are left behind, breathing without them.

Several years before his death, long after Hall stopped actively writing poetry, he published what would be the final collection of his poems before his death. For a constant, lifelong editor of his own work, this is a far more monumental and immutable work than any that preceded it (particularly the door-stopping, career-spanning collection White Apples and the Taste of Stone that coronated his brief moment as poet laureate). On the back of the collection, “Gold”—an older poem, published after his cancer diagnosis but before Kenyon’s—ends with this stanza: “We made in those days / tiny identical rooms inside our bodies / which the men who uncover our graves / will find in a thousand years, / shining and whole.”

Several years before his death, long after Hall stopped actively writing poetry, he published what would be the final collection of his poems before his death. For a constant, lifelong editor of his own work, this is a far more monumental and immutable work than any that preceded it (particularly the door-stopping, career-spanning collection White Apples and the Taste of Stone that coronated his brief moment as poet laureate). On the back of the collection, “Gold”—an older poem, published after his cancer diagnosis but before Kenyon’s—ends with this stanza: “We made in those days / tiny identical rooms inside our bodies / which the men who uncover our graves / will find in a thousand years, / shining and whole.”

Image: Vitro Nasu