1.

“How many of you still play with dolls?”

Depending on our moods: We rolled our eyes; we buried our burning faces in our arms; we groaned; we shrieked; we wished to be elsewhere; we were present.

In the exact middle of eighth grade (the season in which cold, gray rain sweeps across Northern California) we heard a speech in euphemism. We (the Marymount plaid-plastered hoard of girls I had been enmeshed in since I was 9, the girls who hugged and cried and tried to cut off one another’s prettiest braids with safety scissors in moments of hideous envy) were eating our lunches at our desks as our principal stood before us. I must have been eating a liverwurst sandwich—I know this because I was crazy about liverwurst for most of that year. Eventually, I learned that this was a bad way to distinguish myself, so I stopped.

Around that time, I began to believe that a woman should tailor her existence so that each detail of herself is optimally alluring. If I saw a woman in a Wes Anderson movie place yellow binoculars on a red desk, I processed this aesthetic choice as a reflection of her worthiness and her ability to be permanently stylish. I thought that if I were able to arrange myself accordingly, some stray ephemeral beauty might drift toward me, too. Then, life would be sunny and warm.

Anyway, the detail of a liverwurst and cheese sandwich has never been used as a symbol of a woman’s alluring, monochromatic essence. This type of sandwich is the mark of a target, of a person whose state of being is not neatly tailored; it is a state of being that reeks of liver breath.

Mrs. Mollan, our principal, was monochromatic in a beige way: She had a sandy blond bob; she wore tan cardigans and straw-colored shoes. She told me once that she’d always wanted to be a librarian or a school teacher. At age 14, this sentiment reminded me of It’s a Wonderful Life and the alternate reality in which Mary Bailey becomes a librarian because she is an old maid. I had this idea that women from a certain time were forced to choose from a slim, creaky list of career paths. Even if they distinguished themselves, I thought, these women were disappointing because they had found success in a field that was dictated to them. I wasn’t sure who dictated what, but I was convinced that choosing between becoming a librarian or a teacher felt like a certain type of cage.

Years later, I thought I might like to either become a teacher or a librarian. When I was 14 I did not understand anything more subtle than a neon sign and I am not unique in that.

Mrs. Mollan said, “My youngest son has always had the same best friend. Last week, they both came over for dinner. I asked my son’s friend if he was dating anyone. He said, ‘I’m seeing this new girl.’ So I said, ‘Well, what is she like? Is she going to bring you home to her parents? Will you bring her home to your parents?’’’

We’d skipped the chapter in our religion book that mentioned sex. I read it anyway; it was really about pregnancy. It described the gift of life alongside a few scenarios featuring girls in trouble. Love applied to God, life applied to babies, and the mechanics belonged to a nothingness that was instinct.

“Do you know what my son’s friend said when I asked him about his girlfriend?” We shook our heads. “He laughed! He said, ‘I would never bring her home to my mother. She’s not that type of girl.’”

Mrs. Mollan said, “Keep playing with dolls. Act your age. You don’t want to be that type of girl. You have 15 minutes left for lunch outside.”

We were released. That was all the sex ed we got.

We stampeded from the classroom. The boys in our class asked us why we’d been kept inside. We said, “Something stupid.” We were children; we were used to being lectured.

2.

Our school was called St. Lawrence and it was long and flat, the type of school that was spread out instead of built up. It was tucked behind a massive church that had a blank white face; a single round, stained glass cyclops eye; and pillars for teeth. The school lolled out behind the church like a stucco tongue.

There was occasional violence here. Strange kids came to St. Lawrence to hurl limes at us. Neighbors from the adjacent apartments threw rocks. We all laughed at whoever was hit. An elderly man nobody knew wandered around the monthly mass in a priest costume, asking children for hugs. When this made the local news, the school banned him. He began standing by an empty storefront three blocks away, dressed as Santa Claus. Though these inconveniences had always existed, always, we were fascinated by them; we thought they were very new.

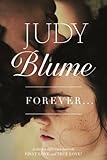

If we looked long and hard at certain books, we could trace threads of the mechanics. There was a copy of Judy Blume’s Forever… that circulated among us, but Judy Blume was one of my mother’s favorite authors, so I was unimpressed. I reasoned that anything that had once taught my mother about sex was inherently useless. Plus, the protagonist in Forever… is a girl named Katherine who has long blond hair and symmetrical features; she casually travels to New York City alone to obtain birth control; she is wealthy and white. I felt a rabid jealousy. Answers were hard to find.

If we looked long and hard at certain books, we could trace threads of the mechanics. There was a copy of Judy Blume’s Forever… that circulated among us, but Judy Blume was one of my mother’s favorite authors, so I was unimpressed. I reasoned that anything that had once taught my mother about sex was inherently useless. Plus, the protagonist in Forever… is a girl named Katherine who has long blond hair and symmetrical features; she casually travels to New York City alone to obtain birth control; she is wealthy and white. I felt a rabid jealousy. Answers were hard to find.

I found a different book, one that my mother first told me about in heavily curated snippets: Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones. When my mother took a trip to Los Angeles, I snuck the book off her shelf and read it on her square, green bed.

I found a different book, one that my mother first told me about in heavily curated snippets: Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones. When my mother took a trip to Los Angeles, I snuck the book off her shelf and read it on her square, green bed.

At first, this made me feel as grown as I did when my parents let me have a quarter glass of wine at dinner. It didn’t last: The protagonist, a girl named Susie, is sexually assaulted and killed. Reading that book felt like someone in desperate pain was squeezing my hand.

For years, Susie watches her family from heaven. Eventually, she possesses a woman on earth. Susie uses the woman’s body to approach a man she had loved when they were both children. They have exquisitely healing sex that alleviates Susie’s grief. “While he rested, I kissed him across the line of his backbone and blessed each knot of muscle, each mole and blemish.” The violence ends. It was the first time I learned that sex could repair a broken person, like an epoxy.

3.

Soon enough, my mother handed me her copy of Middlesex; this book held my favorite answers. My closest friends and I fell in love with the protagonist, a girl named Calliope. We learned that Calliope is obsessed with hair removal, she prays to be different (as in: the same as everyone else), and she adores a messy redhead whom she calls “the Obscure Object.”

Soon enough, my mother handed me her copy of Middlesex; this book held my favorite answers. My closest friends and I fell in love with the protagonist, a girl named Calliope. We learned that Calliope is obsessed with hair removal, she prays to be different (as in: the same as everyone else), and she adores a messy redhead whom she calls “the Obscure Object.”

The Obscure Object is as WASPy and privileged as Katherine in Forever… but she is lazier. She wears shoes with the ends stamped down and shuffles in them like slippers (for months, we copied this as if it were a magic formula for beauty, we compromised many sneakers). The Obscure Object sneaks cigarettes all damn day and later on I tried that, too.

Calliope’s parents and teachers are too prudish to teach her about sex, so she learns by guessing. She guesses that her body is out of her control. She prays for her entire self to morph into an avatar of standard girlishness.

Like Calliope, we prayed—at mass, in class each morning, before bed, alone. There were prayers for money, for God to administer cooler clothes; there was “I’ll be good forever if you change my entire face on the count of five.”

Eventually, Calliope realizes that she is intersex. Her body startles her. Her prayers are meaningless. She lies to her family. She learns to withhold. She has frenzied, loving sex with the Obscure Object. Their sex is also an act of guessing.

Even without instruction, we began to learn. We learned that lying and keeping grand secrets might be a sliver of God’s love and gander. Calliope lies her way out of everything until she gets the courage to run away. Lies held mercy. I also wanted to love redheaded girls who smoked too much. I wanted to run off into a dark, grimy otherness. There were a lot of lies to be told.

Nothing changed immediately. At St. Lawrence, we spent hours watching television shows starring ’80s kids with bowl cuts who praised God in order to resist hand-rolled cigarettes. We sat; we waited; we grew. We read semi-contraband books during Sustained Silent Reading. We were a pile of bodies drifting toward the unspoken (always appearing to act our age). We ruined our sneakers by stamping them into slippers and arranged ourselves precisely.

Image: Pexels/icon0.com.