On April 16, 2018, Junot Díaz came forward in a daring New Yorker piece sharing his story as a survivor of childhood sexual assault. Fast-forward to May 4—Díaz appears once more in newspapers, this time in the New York Times, as the subject of accusations of sexual misconduct (“The Writer Zinzi Clemmons Accuses Junot Díaz of Forcibly Kissing Her”). Clemmons was quickly supported by Carmen Maria Machado and Monica Byrne, both of whom gave accounts of being subject to disproportionate aggression from Díaz.

This came on the same day as the Swedish Academy’s announcement that no Nobel Prize in Literature would be awarded this year, “in view of the currently diminished Academy and the reduced public confidence in the Academy.” This followed the disgrace of Jean-Claude Arnault, husband of Academy member Katarina Frostenson; Arnault faces allegations of sexual assault from 18 women as well as an investigation over the leak of the names of seven Nobel literature laureates.

Three days later, New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman resigned following a #MeToo exposé as four women, including Michelle Manning Barish and Tanya Selvaratnam, revealed accounts of physical and emotional abuse at his hands. The #MeToo movement has become a formidable force following the fall of media mogul and serial abuser Harvey Weinstein—and subsequent revelations of misconduct surrounding R. Kelly, Aziz Ansari, and James Franco, just to name a few. The movement became so widespread that the Time “Person of the Year” was named “The Silence Breakers.”

The seeds of #MeToo were planted more than 10 years ago with the work of activist Tarana Burke (whose thoughtful reflections can be found here). Burke’s original campaign offered survivors of sexual violence, mainly women of color, an avenue to ask for help with the neutral, short signal of “Me Too.” Her work is predicated on the statistically proven greater likelihood of women of color becoming victims of domestic violence and/or sexual assault. Violence against women, understood as a tool for continued control and subjugation, occurs at higher rates in poor and immigrant communities. Undocumented immigrants, poor women of color and trans women also disproportionately underreport sexual violence, meaning that many continue to suffer in silence.

#MeToo is thus crucially not just an Anglo-American, white phenomenon, and it is spreading around the world. Women in China, for example, are beginning to use the hashtag (cleverly dodging censors with the homophone #MiTu, meaning “rice bunny”), chiming in with women from Finland, Spain, Vietnam, and more. Where there is patriarchy and where male power has been institutionally ratified, #MeToo will naturally (and rightfully) put down roots. The literary community is no exception and must contend with its own ability to provide responses. How can writers speak for those just learning to tell their stories? Can we? Should we? Can any writer with the privilege of success, class, whiteness, or maleness even ethically tackle the complexities of contemporary gender politics?

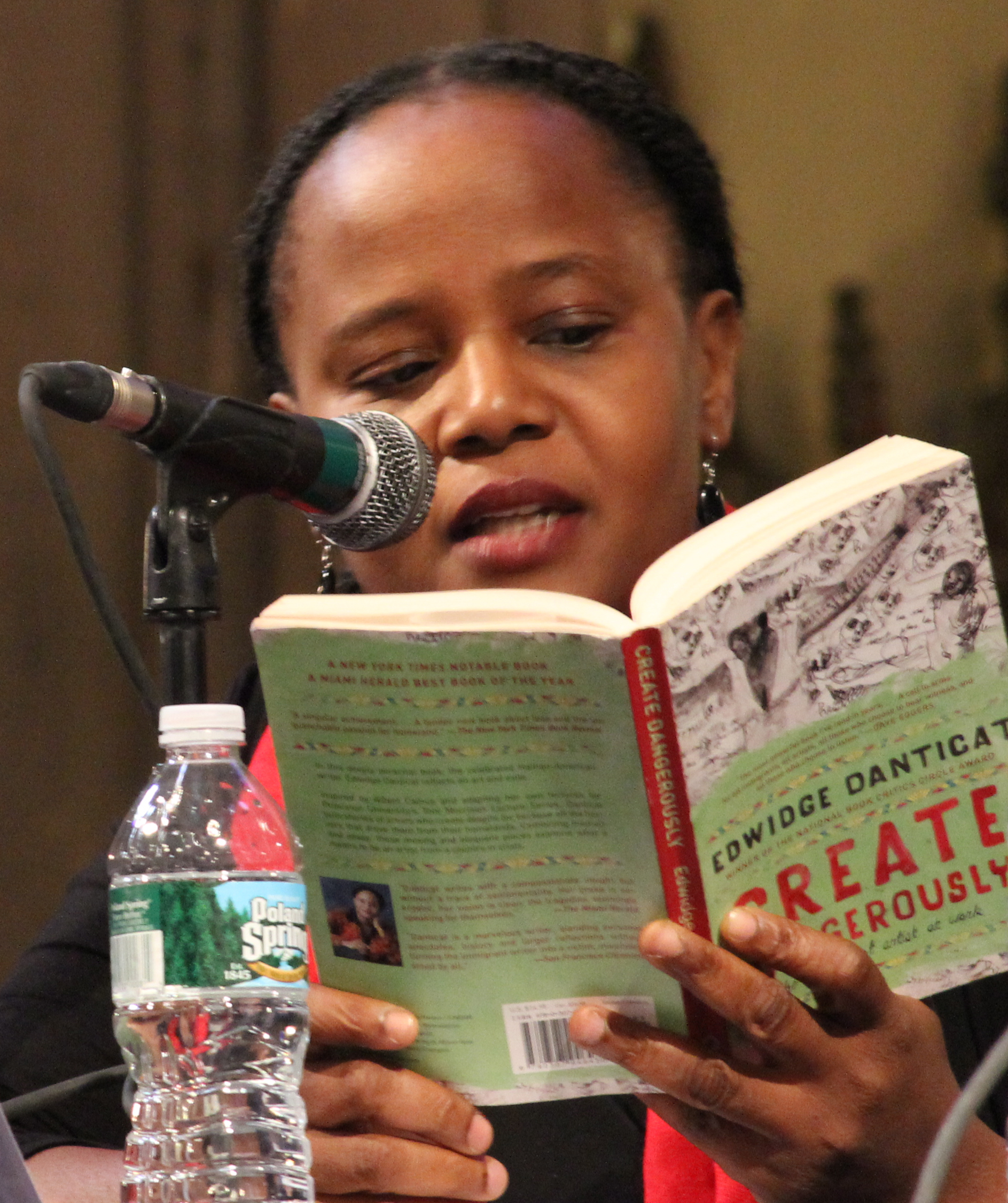

Here’s where Edwidge Danticat steps in.

A remarkably prolific author, Danticat is particularly dexterous with genre, stepping in and out of the parameters of novel, short story, testimonial, and biography throughout her oeuvre. Her most recent publication, The Art of Death (Graywolf Press, July 2017), was nominated for the 2017 National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism and is impressive in demonstrating her wide reading as well as talent for deeply introspective prose as she reflects on her mother’s death. Raised in Haiti before moving to Brooklyn, N.Y., at the age of 12, Danticat’s works have been doing the work of #MeToo for over a decade longer than the movement has existed.

A remarkably prolific author, Danticat is particularly dexterous with genre, stepping in and out of the parameters of novel, short story, testimonial, and biography throughout her oeuvre. Her most recent publication, The Art of Death (Graywolf Press, July 2017), was nominated for the 2017 National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism and is impressive in demonstrating her wide reading as well as talent for deeply introspective prose as she reflects on her mother’s death. Raised in Haiti before moving to Brooklyn, N.Y., at the age of 12, Danticat’s works have been doing the work of #MeToo for over a decade longer than the movement has existed.

In particular, her first novel, Breath, Eyes, Memory, revolves around the stories of women who have suffered the trauma of sexual violation. Sophie Caco, the narrator of the story, is sexually abused by her mother within the tradition of “testing,” where daughters are penetrated to verify that their hymens are intact, and therefore their virginity too. Raised by her Tante Atie after her mother, Martine, flees Haiti, Sophie only learns later that Martine was raped by a Tonton Macoute, one of François Duvalier’s army. This results in Sophie’s birth and Martine’s lifelong nightmares and psychosis. Martine’s fears add to her socially inherited paranoia over Sophie’s virginity, leading to the testing and the accompanying story of the Haitian “Marassas.” Martine narrates:

In particular, her first novel, Breath, Eyes, Memory, revolves around the stories of women who have suffered the trauma of sexual violation. Sophie Caco, the narrator of the story, is sexually abused by her mother within the tradition of “testing,” where daughters are penetrated to verify that their hymens are intact, and therefore their virginity too. Raised by her Tante Atie after her mother, Martine, flees Haiti, Sophie only learns later that Martine was raped by a Tonton Macoute, one of François Duvalier’s army. This results in Sophie’s birth and Martine’s lifelong nightmares and psychosis. Martine’s fears add to her socially inherited paranoia over Sophie’s virginity, leading to the testing and the accompanying story of the Haitian “Marassas.” Martine narrates:

They were the same person, duplicated in two. They looked the same, talked the same, walked the same.

The love between a mother and daughter is deeper than the sea. You would leave me for an old man who you didn’t know the year before. You and I we could be like Marassas.

Ironically, however, Sophie mirrors Martine in another way; they both become victims of sexual violence through the socially sanctioned abuses of power of the Tonton Macoutes as well as the patriarchal cult of virginity. Plagued by nightmares and delusions of the voice of her rapist speaking to her from her fetus, Martine eventually kills herself by stabbing her stomach 17 times. It is crucial in Breath, Eyes, Memory that Sophie and Martine are “twinned,” as it is only through Sophie that Martine’s story is told. Sophie as a foil for Martine demonstrates that for every woman who has been able to overcome her trauma, there are others who are unable—whose present remains overwhelmed by their past, obstructing any meaningful catharsis.

Only in death does Martine triumph, as she is dressed by Sophie in bright red, “too loud a color for a burial.” Martine thus “would look like a Jezebel, hot-blooded Erzulie who feared no men, but rather made them her slaves, raped them, and killed them” (emphasis author’s). The metaphor for Martine as Erzulie, a Vodou goddess with different forms, combines within Martine a myriad of female characters. Earlier in the text, Martine is compared to the maternal Erzulie Dantor, “the healer of all women and the desire of all men.” At the end of the text, however, the “hot-blooded Erzulie” is a manifestation of the flirty and sensual Erzulie Freda. The binary of the Madonna-whore is thus challenged within the Erzulie figure, while victims of sexual assault are underscored as not necessarily one or the other.

Danticat’s writing also captures the complexity of abuses of power that have plagued the #MeToo movement as detractors respond to the flood of testimonies in varied ways. Notably, the New York Times published an opinion piece defending Aziz Ansari’s actions, claiming he could not have been expected to know Grace’s (not her real name) discomfort and that “The insidious attempt by some women to criminalize awkward, gross and entitled sex takes women back to the days of smelling salts and fainting couches.” More recently, director Roman Polanski (of The Pianist fame) sued the Oscars academy following his expulsion after sexual assault revelations against him, calling the #MeToo movement “mass hysteria.” Earlier in May, Chitra Ramaswamy questioned how to respond to Junot Díaz being both a victim and perpetrator of sexual assault and misconduct.

This writer suggests Danticat’s The Dew Breaker (2004) as a launchpad for discussion. The Dew Breaker features nine stories, three of which revolve around “the Dew Breaker” (translated from chouket laroze, a colloquialism for “torturer” in Haitian Creole), three that concern Haitian men he rents a basement apartment to (“Seven,” “Monkey Tails,” “Night Talkers”), and three affiliated to this network (“The Bridal Seamstress,” “Water Child,” “Funeral Singer”). The Dew Breaker’s life in Brooklyn and Florida remains plagued by insecurity over the revelation of his past, while the family members of his victims continue to agonize over the deaths or traumas he is responsible for.

This writer suggests Danticat’s The Dew Breaker (2004) as a launchpad for discussion. The Dew Breaker features nine stories, three of which revolve around “the Dew Breaker” (translated from chouket laroze, a colloquialism for “torturer” in Haitian Creole), three that concern Haitian men he rents a basement apartment to (“Seven,” “Monkey Tails,” “Night Talkers”), and three affiliated to this network (“The Bridal Seamstress,” “Water Child,” “Funeral Singer”). The Dew Breaker’s life in Brooklyn and Florida remains plagued by insecurity over the revelation of his past, while the family members of his victims continue to agonize over the deaths or traumas he is responsible for.

To consider Danticat’s themes of guilt, responsibility, and concealment is to reflect on consent and power outside the legal system and to demand better from men. Rather than indulging female weakness or encouraging female delicacy, men are to be held accountable for their past mistakes while coming to terms with the violence they are capable of, the violence that has long been enabled by a patriarchal society, just as the Dew Breaker himself was authorized by Duvalier’s dictatorship. The Dew Breaker demonstrates that victims are far from weak, rather that complicity with systems of power has long-term consequences for abusers and victims alike, as well as their families. Power and its use do not produce a binary of good and evil, but instead a web of concealment, shame, guilt, anger, and trauma.

The use of the short story cycle and anachronistic form is particularly potent in connecting narratively independent pieces in a thematic consideration of the consequences of violence, from both the perspective of the abuser and the victims. Like many of the stories of #MeToo, the story of the Dew Breaker is not straightforward, and Danticat avoids a prescriptivist approach to the revelation of his crimes. What is more important, however, is the beginning of a larger conversation over who holds power, the conditioning of men toward violence, and the ability of victims (like “the seamstress,” for example) to resist or to tell their stories. As the first book in Danticat’s career that shifts toward an extended interrogation of paternal relationships, The Dew Breaker is a particularly useful text in raising questions of gendered power as well as the extent to which abusers are and remain culpable for their actions.

As a female African-Haitian-American writer (as Danticat refers to herself in her essay “AHA!”), Danticat also descends from a rich tradition of black women’s writing as well as Haitian political writing. Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, for example, (in Martin Munro’s Edwidge Danticat: A Reader’s Guide, 2010) identifies Danticat’s work as addressing similar themes to black women’s writing in America (think Phillis Wheatley, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker), such as female relationships, motherhood, and political resistance. Female testimony combats the erasure of women’s histories.

As a female African-Haitian-American writer (as Danticat refers to herself in her essay “AHA!”), Danticat also descends from a rich tradition of black women’s writing as well as Haitian political writing. Régine Michelle Jean-Charles, for example, (in Martin Munro’s Edwidge Danticat: A Reader’s Guide, 2010) identifies Danticat’s work as addressing similar themes to black women’s writing in America (think Phillis Wheatley, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker), such as female relationships, motherhood, and political resistance. Female testimony combats the erasure of women’s histories.  In The Farming of Bones (1998), for example, narrator Amabelle Desir tells the story of the 1937 Parsley Massacre, where Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the murders of thousands of Haitians and Haitian Dominicans. Amabelle’s story places women in the historical narrative, reminding readers that women were there and providing a testimony (if fictional) to the lives lost.

In The Farming of Bones (1998), for example, narrator Amabelle Desir tells the story of the 1937 Parsley Massacre, where Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the murders of thousands of Haitians and Haitian Dominicans. Amabelle’s story places women in the historical narrative, reminding readers that women were there and providing a testimony (if fictional) to the lives lost.

On the other hand, Danticat descends also from a Francophone Haitian literary tradition and names amongst her inspirations Frankétienne and Marxist Jacques Roumain, as well as novelist-journalist Dany Laferrière. In particular, The Dew Breaker makes a reference in its title to Roumain’s Gouverneurs de la Rosée (Masters of the Dew), published in 1944. Haitian literature is inseparable from its political history, which has long identified itself with leftist resistance dating from the 1804 Revolution where Haiti became the first black republic, the only to be formed from a successful slave revolt. Threads, therefore, of the right of individuals to become self-fulfilled and self-determined have long characterized Haitian literature. The combination of Haitian and black women’s writing traditions within Danticat’s oeuvre thus generates a body of work interested in the rights of women, writing in the spirit of universal egalitarianism, and resisting dominant political structures including violent dictatorships and patriarchy.

On the other hand, Danticat descends also from a Francophone Haitian literary tradition and names amongst her inspirations Frankétienne and Marxist Jacques Roumain, as well as novelist-journalist Dany Laferrière. In particular, The Dew Breaker makes a reference in its title to Roumain’s Gouverneurs de la Rosée (Masters of the Dew), published in 1944. Haitian literature is inseparable from its political history, which has long identified itself with leftist resistance dating from the 1804 Revolution where Haiti became the first black republic, the only to be formed from a successful slave revolt. Threads, therefore, of the right of individuals to become self-fulfilled and self-determined have long characterized Haitian literature. The combination of Haitian and black women’s writing traditions within Danticat’s oeuvre thus generates a body of work interested in the rights of women, writing in the spirit of universal egalitarianism, and resisting dominant political structures including violent dictatorships and patriarchy.

This political imperative has remained consistent and unwavering, combining the personal with grand political narratives and seeing both as necessarily co-existent. Danticat’s 1996 essay “We Are Ugly, but We Are Here,” for instance, details the continued resistance of Haitian women from the time of Spanish colonialism dating from the murder of Taino Queen Anacaona, who chose to die rather than become a concubine to the invaders. The figure of Anacaona simultaneously resists colonial exploitation and sexual violence, while predating the destruction of the Taino community and the formation of the African diaspora through slavery in Haiti.

This political imperative has remained consistent and unwavering, combining the personal with grand political narratives and seeing both as necessarily co-existent. Danticat’s 1996 essay “We Are Ugly, but We Are Here,” for instance, details the continued resistance of Haitian women from the time of Spanish colonialism dating from the murder of Taino Queen Anacaona, who chose to die rather than become a concubine to the invaders. The figure of Anacaona simultaneously resists colonial exploitation and sexual violence, while predating the destruction of the Taino community and the formation of the African diaspora through slavery in Haiti.

The “daughters” of Anacaona, bearing the same spirit of resistance and female solidarity, exist throughout Danticat’s work, creating matrilineal communities of women holding each other up through the oral tradition of storytelling, as seen in the short story collection Krik? Krak! (1996). Formed of nine short stories, the collection as a whole connects the lives of “Women Like Us” (the title of the epilogue), as the protagonists of all nine stories are revealed to be connected. A daughter visits her mother who has been imprisoned for being a witch in “Nineteen Thirty-Seven”; a mother-daughter pair attend the funeral of “boat-people” in “Caroline’s Wedding”; the story of Célianne, victim of rape and one of the drowned, is told in “Children of the Sea.”

The lives of women are revealed to be linked and brought together by shared tradition and narrative, while the text acts as testimony for their lives, putting their stories on the page just as #MeToo has done for women. As Nick Nesbitt astutely comments, “Such a politics of solidarity would erase distinctions of the personal and political that have historically allowed for various forms of injustice to continue unabated in the ‘private’ sphere.” Danticat’s writing proves that discussions of politics, Haitian dictatorships, and the formation of the Haitian diaspora are ultimately only rendered complete when private, individual lives are also considered.

Regardless of what you think of the movement or how uncomfortable female confession makes you, #MeToo is not going away anytime soon. To quote Danticat from “We Are Ugly”: “The daughters of Anacaona. We have stumbled, but have not fallen. We are ill-favored, but we still endure. Every once in a while, we must scream this as far as the wind can carry our voices: We are ugly, but we are here! And here to stay.” To read Danticat is to confront the same issues that the #MeToo movement does—issues of gender politics, female solidarity and resistance as well as the construction of male roles in patriarchal societies. As #MeToo goes global, we need to think about the stories of women around the world—and the works of Edwidge Danticat are as good a place as ever to begin.

Image: Flickr/editrrix