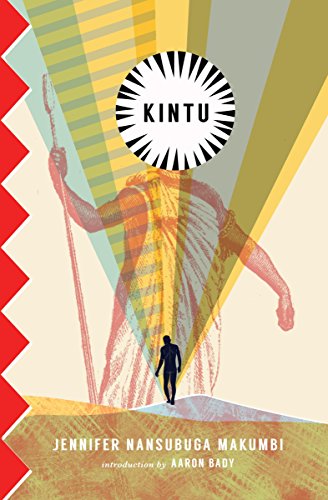

In March, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi became a 2018 recipient of the $165,000 Windham Campbell Prize, one of the world’s most generous writing awards. Five years ago, when the Ugandan-born author completed her doctoral thesis, the novel Kintu, at the University of Lancaster in the U.K., she was unable to find a publisher in in the UK willing to publish it.

Makumbi’s novel makes a fine ambassador for her bookish compatriots in Kampala, Uganda’s capital city. Kintu follows one Ugandan family across centuries of Ugandan history. It doesn’t stray into other lands or continents. It skips right over Uganda’s British colonial experience. It doesn’t dwell on the most internationally famous aspects of Ugandan contemporary history.

The first book of Kintu opens with the lines:

It was odd the relief that Kintu felt as he stepped out of his house. A long and perilous journey lay ahead.

A half-century ago, Uganda was an African literary powerhouse. In 1961, a 22-year-old Rajat Neogy established Transition Magazine: An International Review, arguably sub-Saharan Africa’s all-time most influential literary journal, in Kampala. The great Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o says in his 2016 memoir, Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer’s Awakening, that the time he spent from 1959 to 1964 as a student at Makerere University, Uganda’s premiere seat of higher education, made him the writer he is today.

A half-century ago, Uganda was an African literary powerhouse. In 1961, a 22-year-old Rajat Neogy established Transition Magazine: An International Review, arguably sub-Saharan Africa’s all-time most influential literary journal, in Kampala. The great Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o says in his 2016 memoir, Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Writer’s Awakening, that the time he spent from 1959 to 1964 as a student at Makerere University, Uganda’s premiere seat of higher education, made him the writer he is today.

Makerere hosted, in 1962, the first major international gathering of writers and critics of African literature in Africa. Held right as many African nations were breaking free from colonialism and attracting participants such as Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Langston Hughes (although as a non-African Hughes could only be an “observer”), the First African Writers Conference is often said to have cemented the concept of an “African” writer. It’s also where the young Ngũgĩ slipped the manuscript of what would become his first published novel, Weep Not, Child, to Achebe who, duly impressed, passed it along to his editors at Heinemann in London.

Makerere hosted, in 1962, the first major international gathering of writers and critics of African literature in Africa. Held right as many African nations were breaking free from colonialism and attracting participants such as Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Langston Hughes (although as a non-African Hughes could only be an “observer”), the First African Writers Conference is often said to have cemented the concept of an “African” writer. It’s also where the young Ngũgĩ slipped the manuscript of what would become his first published novel, Weep Not, Child, to Achebe who, duly impressed, passed it along to his editors at Heinemann in London.

All of this pioneering activity in Kampala might seem to have laid fertile ground for the emergence already in the 1960s and 1970s of a powerful Ugandan writerly tradition. Certainly, the Ugandan landscape offers rich poetic inspiration and its history a surfeit of dramatic material. But politics can both feed literary output and obstruct it.

Before becoming a British protectorate in 1894, modern-day Uganda was split among separate but interrelating kingdoms and chieftaincies; Kintu, which reaches back into the 1750s, offers a vibrant depiction of how this worked. After achieving independence in 1962, these kingdoms struggled to find a peaceable alliance again.

For a while, Transition continued to print work by Achebe, James Baldwin, and Julius Nyerere. At Makerere, visiting scholar Paul Theroux and writer-in-residence V.S. Naipaul began the great friendship that would eventually give way to their infamous feud.

Under the second president, Milton Obote, however, political strings began tightening. Then came the 1970s and the power grab of Idi Amin, a professional soldier with a sixth-grade education and a profound distrust of intellectuals. During Amin’s eight years from 1971 to 1979 as Ugandan president, the country’s established literati for the most part either fled or went silent. A fractious reappearance by Obote in the early 1980s did nothing to encourage their return.

That doesn’t mean storytelling stopped altogether. “What I don’t agree with,” popular Ugandan poet Ngobi Kagayi says, “is the idea that because people stopped producing literature, literature died. Literature doesn’t belong to the writers.”

Uganda’s oral tradition persisted, something that plays an integral part in Kintu. It also informs Kagayi’s poetry. Kagayi’s broad-ranging and consistently clear-voiced debut collection, The Headline That Morning, published under the name Peter Kagayi, contained a CD on its back flap; fittingly, the opening poem in the collection is entitled “Listening to Poetry”:

Today we shall listen to poetry

While seated comfortably

Yesterday we listened to guns coughing

And wails of pain as blood was gushing

While we hide our heads in our beds.

Tomorrow we shall have what to do after the election campaigns

But today? Today we shall listen to poetry

While seated comfortably.

Nayana Kakoma, whose all-Ugandan Sooo Many Stories (tagline: “Tales from Here and There”) published The Headline That Morning, recognized a Ugandan audience as accustomed to listening to its literature as to reading it.

Kakoma is a member of FEMWRITE, an NGO established in Kampala in 1995 by parliamentarian Mary Karooro Okurut with the goal of helping Ugandan women make gains in literacy, as well as to show them a way in which literacy could be of value to them. Literacy in Uganda has steadily risen over the last two decades, although women still lag behind men. At the time of FEMRITE’s inception, the rate for women was at less than 50 percent.

Through workshops and a publishing arm, FEMRITE has encouraged Ugandan women of all levels of education to believe they too can be writers.

“I met writers I had read and admired,” Beatrice Lamwaka, the current general secretary of PEN/Uganda, says, “and I noticed that they were not any different from me.” In 2011, Lamwaka’s short story, “Butterfly Dreams,” inspired by her late brother’s experience as child soldier in the Lord’s Resistance Army, was shortlisted for the coveted Caine Prize for African Writing.

A marked success, FEMRITE now works with women all over Africa. Members Goretti Kyomuhendo and Beverley Nambozo have gone on to establish, respectively, the African Writers Trust, which facilitates collaboration between writers in Africa and its diaspora, and the Babishai Niwe Poetry Foundation, an annual poetry competition initially for Ugandan women but now open to all Africans of any gender.

Kagayi’s introduction both to being a poet and a literary activist began through a different grassroots group, The Lantern Meet for Poets, a collaborative writing workshop begun in a dorm room in Kampala in 2007. He also belongs to yet another grassroots group, Writivism, an ambitious six-step program dedicated to creating a future generation of writers. “Writivism was established not so much as an infrastructure, because you can’t do everything,” explains its co-founder Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire. “It is a community that is doing activism for these things.”

Cultivating a new generation of writers and readers in Uganda, rated the 25th-poorest country in the world by the IMF in 2016, is a complex task. Public primary schools average 43 students to every teacher, and sometimes many more, and with Ugandan women giving birth to an average of 5.7 children, private schools necessitate a financial outlay beyond the reach of many families. Meanwhile, curricula remains rooted in outdated models from British colonialism.

In addition, bookstores are few and, in a country where homes typically do not have street addresses, a door-to-door postal delivery system doesn’t exist. Writivism members go into schools, run workshops, and hold contests, encouraging both writing and reading. Turn the Page, a Kampala-based online book club run by Alex Twinokwesiga, has added a distribution wing to tackle the problem of getting books to readers around Uganda.

In establishing Sooo Many Stories, Kakoma hoped also to offer Ugandan writers—who rely largely on the Internet (Facebook, Twitter, and WordPress) to share their work—the possibility of seeing their work on paper and maybe to earn money from it without having to join the African literary diaspora.

Here too the task has not been simple; with a lack of local resources as basic as suitable paper, Kakoma had to turn to Nairobi to print Kagayi’s collection. In 2017, however, Kakoma managed to print Sooo Many Stories’ second offering, an East African edition of Flame and Song, a genre-transcending poetry-and-prose-blending memoir of privileged childhood in Uganda and subsequent exile by Philippa Namutebi Kabali-Kagwa:

Here too the task has not been simple; with a lack of local resources as basic as suitable paper, Kakoma had to turn to Nairobi to print Kagayi’s collection. In 2017, however, Kakoma managed to print Sooo Many Stories’ second offering, an East African edition of Flame and Song, a genre-transcending poetry-and-prose-blending memoir of privileged childhood in Uganda and subsequent exile by Philippa Namutebi Kabali-Kagwa:

I made friends with Silas and Paul, who lived up the road, and Charlie, who lived across the road. We rode bicycles up and down the hill every day. I even learnt to ride without holding my handlebars. I had cropped hair then and was often in shorts or trousers, and I was always with the boys. Once, riding past some ladies, I heard them debate my gender.

‘You see that one, she is a girl.’

‘No, it’s a boy. What girl would ride a bicycle like that?’

This spring, Writivism put out Odokonyero: A Writivism Anthology of Short Fiction by Emerging Ugandan Writers, showcasing the work of 18 young up-and-coming Ugandan writers, in cooperation with South-African publisher Black Letter Media. Mwesigire and Madhu Krishnan, a senior lecturer in post-colonial writing at the University of Bristol, co-edited.

This spring, Writivism put out Odokonyero: A Writivism Anthology of Short Fiction by Emerging Ugandan Writers, showcasing the work of 18 young up-and-coming Ugandan writers, in cooperation with South-African publisher Black Letter Media. Mwesigire and Madhu Krishnan, a senior lecturer in post-colonial writing at the University of Bristol, co-edited.

Up in northwestern England, Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi has seen good things for her book. An early East African edition of Kintu came out from the Kwani Trust in Kenya in 2014; in 2017 Transit Books published a U.S. edition. Oneworld Publications released a U.K. edition this January.

Having won the Windham Campbell Prize should allow Makumbi to concentrate on her writing; her next book, the short story collection Love Made in Manchester, is forthcoming in 2019 from Transit Books. The collection looks at the life of Ugandans in the U.K., which Makumbi pointedly refers to as “expat experiences” rather than “migrant stories.”

Makumbi’s success offers evidence that the literary culture envisioned by the likes of Kagayi, Kakoma, and Mwesigire has begun to coalesce not only abroad but, as intended, in Uganda.

Like Achebe’s African trilogy, Kintu examines the power of myth without mythologizing its subject. Both it and Kabali-Kagwa’s memoir represent uniquely Ugandan voices, in conversation with their people. It’s not necessary to know anything about Uganda to appreciate either, but their story, world, and language will be specifically familiar and meaningful to readers from Uganda.

Both books also have repeatedly sold out at Aristoc, Kampala’s main bookstore.

“I feel,” poet Kagayi says, “like the distance between here and New York and here and the person across the street—the person across the street is longer.” Ugandan writers, whether abroad or at home, are making that journey.