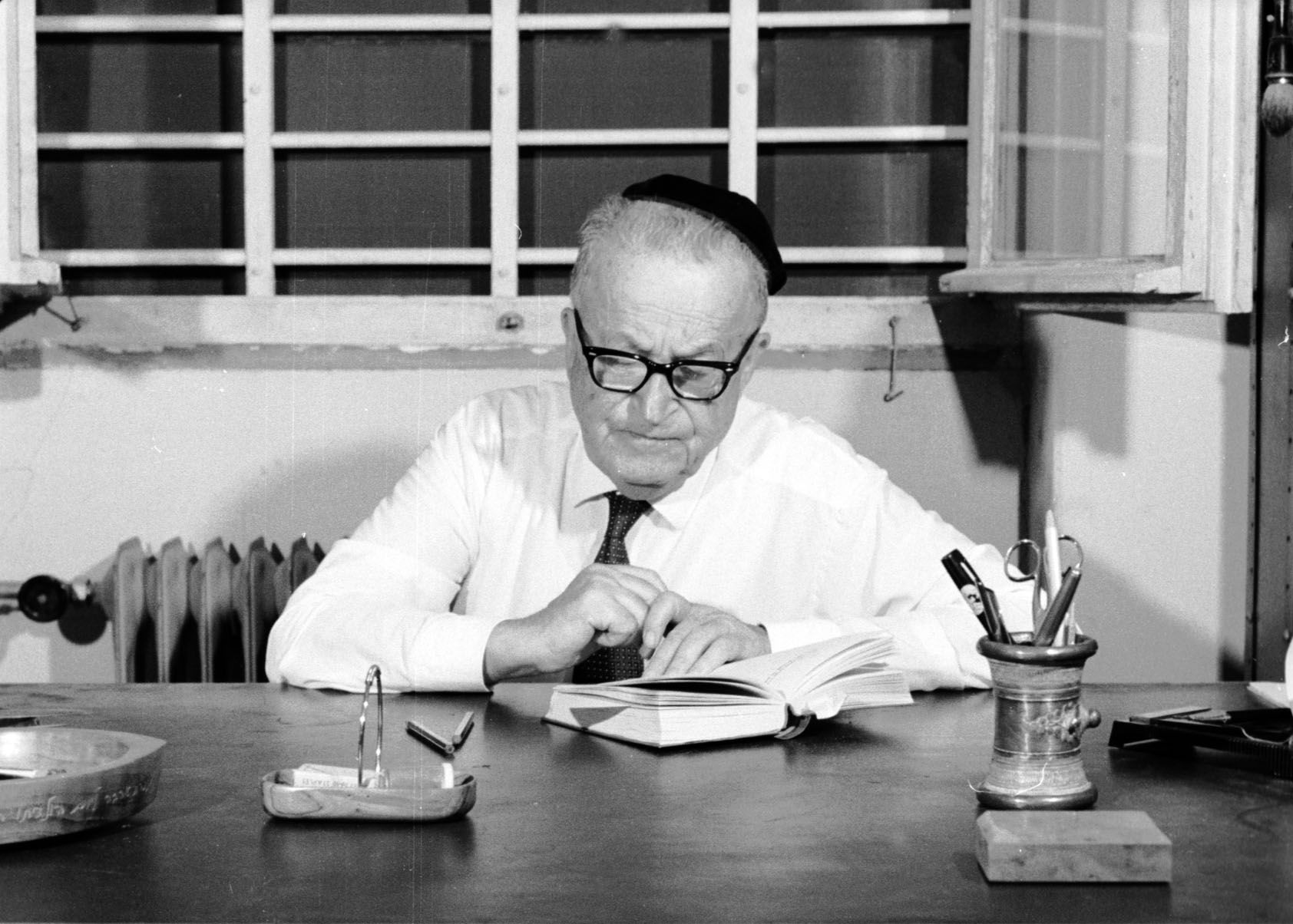

Forty-eight years ago, on February 17, 1970, the great author Shmuel Yosef Agnon passed away in Israel at the age of 82. By the time of his death he was considered one of the greatest writers of modern Hebrew literature. His stature was finally acknowledged only four years earlier, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature, which he shared with the German-Jewish poet Nelly Sachs. Yet outside the narrow circle of Hebrew readers Agnon remains almost unknown. Much of his prodigious oeuvre has not been translated, and even native Hebrew speakers are more likely to recognize his name than to be familiar with more than a few of his stories. Why is it that this extraordinary literary figure has spent the last half-century in such obscurity, and what can be gained from rediscovering his work?

Agnon was born in 1887 as Shmuel Yosef Czaczkes in the small eastern European town of Buczacz and engaged in writing fiction and poetry as a young man. At the age of 21 he immigrated to Palestine, where he published under the pen name Agnon after the title of one of his major early stories, later adopting it as his official name. But in 1912 Agnon moved to Germany, where he lived for the next twelve years. In 1924 Agnon’s house in Bad Homburg burned down; as he noted at the time, “everything I had written from the day I left Israel and went to the Diaspora was burned, as well as the book I had written together with Martin Buber.” It was then that Agnon moved back to Palestine and remained in Jerusalem for the rest of his life.

Agnon’s voluminous writing combined his love for Hasidic tales, his fascination with modernist literature, and his attachment to the world he left behind as a young man and which was eventually wiped out in the Holocaust. Much of the complexity and lushness of his prose is derived from Agnon’s unique use of the revived Hebrew language, which he both molded into a vehicle for literary expression and enriched with linguistic layers from ancient and medieval Jewish sources. But most important is his ability to penetrate into the human soul, always with a measure of irony, never marred by sentimentality, combining almost clinical perceptiveness with boundless empathy. In some ways, reading Agnon is akin to traveling into a lost universe equipped with language one barely controls only to end up reaching into the recesses of one’s own mind.

To me Agnon was and remains a crucial figure for several reasons. First, because his language, as aptly put by the critic Ariel Hirschfeld, “exists in a meta-time of Hebrew,” a “hovering language” that spans the entire vast arc of Jewish civilization. A language that exists beyond time and simultaneously preserves all that time has erased with great precision and plasticity is what every writer should aspire to and very few achieve. Second, because the one time I met Agnon as a young teenager, when he visited my parents’ home in London, my father’s admiration for him—that of a younger Hebrew writer to the master of the craft—inspired me to dedicate my life to writing too. And third, because it eventually dawned on me that my mother had come from the very same town as Agnon, and that my own link to that town, unrecognized or suppressed for many decades, was biographical, cultural, and historical. It was also quite tenuous: had my mother not left Buczacz in 1935, I would have probably never been born.

In 1930 Agnon visited his hometown of Buczacz for the last time. This visit was the origin of his great novel, A Guest for the Night, published on the eve of World War II. The main protagonist, who describes the city as having lost its soul in the aftermath of the devastation of World War I, encounters one of his childhood friends, also visiting Buczacz after many years of living overseas. The two friends reminisce about the great hopes they had in the past, one as a socialist and the other as a Zionist, and ponder how, in their middle years, their aspirations have come to naught and the fond scenes of their youth have turned into dust.

The sense of disillusionment and impending doom that pervades the novel reflected the realities of the time. But no one could have predicted the horror that was about to be unleashed. Under German occupation, the town’s entire Jewish population was murdered and its Polish inhabitants ethnically cleansed. The Ukrainian residents of contemporary Buczacz have very little knowledge of its past and former inhabitants, although their town is surrounded by mass graves stuffed with thousands of corpses. Some years ago Ukrainian Buczacz learned that it was the birthplace of a Nobel Prize Laureate and named a street after him. But only a few pages of Agnon’s work exist in Ukrainian (translated from Polish) and most people do not even know that he wrote in Hebrew.

Agnon dedicated the last two decades of his life to writing about his hometown as a symbol of the world of eastern European Jewry destroyed in the Holocaust. Asked by a literary critic what he was trying to accomplish, he answered simply: “I am building a city.” His vast literary edifice, parts of which have recently been published in an English translation as A City in Its Fullness, edited by the late Alan Mintz and Jeffrey Saks, was published posthumously in 1973. It is, in a sense, a biography of the town, a compilation of tales about its men and women, scholars and workers, young lovers and old rabbis, great yearnings and wretched endings. Agnon described his labor of love, born of sorrow and mourning, in the following words:

I close my eyes, so that I would not see the deaths of my brothers, my fellow townsmen, because of my bad habit to see my city and its slain, how they are tortured by their tormentors and how they are killed in wicked and cruel ways. And I close my eyes for yet another reason, because when I close my eyes I become as it were master of the universe and see what I wish to see. And so I closed my eyes and called upon my city to stand before me, with all its inhabitants, with all its houses of prayer. I put every man in the place where he used to sit and where he studied and where his sons and sons-in-law and grandsons sat – for in my city everyone came to prayer.

This is also the motto of my own book, which tells the story of a community of coexistence in the town of Buczacz, where Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians had lived side-by-side for centuries, and its transformation in to a community of genocide, where neighbor turned against neighbor and a entire civilization was turned into ashes. As a distant and rare remnant of that world, I also tried, in my own way, to bring it back to life and understand the reasons for its destruction. In a certain sense, this labor of love, however painful, gave new meaning to my own existence.