For me, 2017 was the year that journalism nearly supplanted fiction as my reading life’s dominant genre. I started the year in a state of alarm at Donald Trump’s inauguration. Shortly after he took office, I resolved to be a good, engaged citizen after six years of dereliction. Throughout January and February, I attended rallies in the streets of Oakland and Berkeley and at San Francisco International Airport. I participated in phone banks on my weekends, and attended Indivisible meetings in the homes of well meaning Berkeley liberals who turned out to be vicious, tenant-hating NIMBYs. Galvanized by daily affronts to democracy, I called and wrote to senators from states I don’t live in, only to find out later that they probably never received my indignant messages. It wasn’t clear to me that the frenzy of my renewed civic commitment was having much of an impact, but as long as I was in motion, things felt good.

I brought the same zeal to my reading habits. Being a good citizen meant staying abreast of all the news, all the time. I woke up reading about the latest updates on the Steele Dossier, the travel ban, Sebastian Gorka’s strange ties to fringe right-wing Hungarian nationalist organizations, Nazi sympathizers threatening to descend on Berkeley’s campus, etc. I went to sleep reading about Trump’s failure to disclose his tax returns, Trump’s failure to properly divest from his business, Trump’s probable failure to know that Frederick Douglass is dead, etc. I read about the emoluments clause. I read about Sally Yates’s heroism. I read about climate change’s terrifying impact on our environment. I subscribed to The New York Times and The Washington Post, because Democracy Dies in Darkness and I wanted to set my modest graduate student earnings aflame for use as a torch. A stack of New Yorkers gradually replaced the books I usually keep at my bedside: fiction was out, its place usurped by the steady parade of shitty news.

As it turns out, a citizen can be too engaged. I couldn’t keep up the pace; by April, my energy had begun to flag. I ceased calling senators and attending rallies. My Indivisible group’s mournful rehearsals of Trump’s transgressions made the danger feel overwhelming in scale, and that enervated me, made the entire political situation seem impossibly daunting. I felt reactive, like a patient sitting atop a hospital bed with the President as my doctor, my leg jerking into action every time he applied the reflex hammer. Leaping into questionably effective action at every one of his offenses and policy outrages put me in a perpetual state of agitation. It was a lesson in how—and how not—to practice good citizenship.

My reading habits began to feel much the same. What was the yield of all that reading? My attempt at political engagement set my nerves on edge, but I can’t say that it produced a very clear picture of our political situation. Instead, I felt like I’d sidled up to a painting and pressed my nose into the canvas, looking so closely that my eyes could only make out abstract blotches of color and disarticulated units of meaning. My mind felt receptive, but to the wrong things: the flotsam of current events—gossip, conspiracy theories, giddy coronations of errant tax documents as the smoking gun that would trigger imminent impeachment—buffeted my brain. Even worse, the nation’s combative mood seemed to affect our entire intellectual discourse: faced with actual Nazis in the White House and on our college campuses, people seemed less willing to embrace the spirit of inquiry. And so, if I wasn’t stomping through the mental murk of “breaking news,” then I was consuming doctrinaire hot takes on racial appropriation in art and why the concept of free speech was obsolete. Inquiry seemed less important than taking a stand.

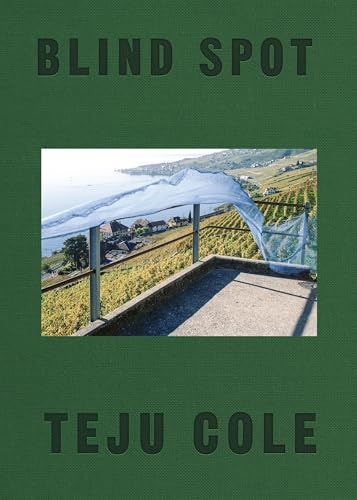

It all got to be too much. Feeling recessed, I plotted an escape from the news’ daily assault. I wanted to return to literature, to fiction and poetry and essays that rewarded slow reading, to pieces that were attentive to the subtleties of race, class, gender, and sexuality but bereft of any agenda other than prompting careful attention and intellectual curiosity. Teju Cole’s monumental Blind Spot was exactly what I needed: an exercise in the right kinds of close attention. It asks us how art might help us compensate for our inability to perceive the world fully. How we can attain a complete—or at the very least, a more complete—sense of the world that we move in? Cole’s photographs and lyrical essays on quotidian sights open up a window into an almost religious realm, one where we become sensitive to the evidence of things not seen.

Cole’s erudite playfulness reminded me what’s possible when a writer looses language from the demands of argument. With that in mind, I resolved to read more poetry as a corrective to my journalism binge. I returned to Gwendolyn Brooks’s Selected Poems, and wondered why no one’s bothered to edit a collected edition of her work. Simone White’s Of Being Dispersed and Douglas Kearney’s Buck Studies were thoughtful—and often hilarious—investigations of what blackness might mean outside of identity’s strictures. Friends brought Bay Area poet Tongo Eisen-Martin’s 2015 book Someone’s Dead Already to my attention, and I was glad to find that this fall City Lights published a new collection of his, Heaven Is All Goodbyes, this year. Eisen-Martin writes with the urgency of a man possessed: by history, by politics, by the dead. When you read his poetry—or, better yet, hear him recite it, oftentimes from memory—it’s hard not to believe that language can set off a revolution. His work peers around the current moment to glimpse those things and people we too often ignore, asking what lessons we can learn from that which society has cast off. That said, he can write some stark summaries of our political situation: “Today I watch capitalism walk on water/And people play dead/So that they can be part of a miracle;” “A politician raises his hand and the crowd shows it’s teeth/an oligarch raises his hand little girls are not safe outside.”

Cole’s erudite playfulness reminded me what’s possible when a writer looses language from the demands of argument. With that in mind, I resolved to read more poetry as a corrective to my journalism binge. I returned to Gwendolyn Brooks’s Selected Poems, and wondered why no one’s bothered to edit a collected edition of her work. Simone White’s Of Being Dispersed and Douglas Kearney’s Buck Studies were thoughtful—and often hilarious—investigations of what blackness might mean outside of identity’s strictures. Friends brought Bay Area poet Tongo Eisen-Martin’s 2015 book Someone’s Dead Already to my attention, and I was glad to find that this fall City Lights published a new collection of his, Heaven Is All Goodbyes, this year. Eisen-Martin writes with the urgency of a man possessed: by history, by politics, by the dead. When you read his poetry—or, better yet, hear him recite it, oftentimes from memory—it’s hard not to believe that language can set off a revolution. His work peers around the current moment to glimpse those things and people we too often ignore, asking what lessons we can learn from that which society has cast off. That said, he can write some stark summaries of our political situation: “Today I watch capitalism walk on water/And people play dead/So that they can be part of a miracle;” “A politician raises his hand and the crowd shows it’s teeth/an oligarch raises his hand little girls are not safe outside.”

In an attempt to understand the histories that have led Californians to what sometimes feels like the precipice of an apocalypse, I also went on a nonfiction binge. I returned to Mike Davis’s classics City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear for a materialist history of our housing and environmental crises. Kevin Starr’s more hopeful, but no less incisive, volumes Endangered Dreams and Coast of Dreams (sensing a theme?) are magisterial in their sweep. Jerald Podair’s City of Dreams was a riveting history of Dodgers Stadium and its central role in Los Angeles’s history. Kellie Jones’s South of Pico taught me about a black Los Angeles arts culture whose extent I was not aware of. Her book also does a great job illustrating how the birth and death of minority arts cultures in California are always bound up in the question of what kind of cities Los Angeles and San Francisco want to be.

In an attempt to understand the histories that have led Californians to what sometimes feels like the precipice of an apocalypse, I also went on a nonfiction binge. I returned to Mike Davis’s classics City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear for a materialist history of our housing and environmental crises. Kevin Starr’s more hopeful, but no less incisive, volumes Endangered Dreams and Coast of Dreams (sensing a theme?) are magisterial in their sweep. Jerald Podair’s City of Dreams was a riveting history of Dodgers Stadium and its central role in Los Angeles’s history. Kellie Jones’s South of Pico taught me about a black Los Angeles arts culture whose extent I was not aware of. Her book also does a great job illustrating how the birth and death of minority arts cultures in California are always bound up in the question of what kind of cities Los Angeles and San Francisco want to be.

My reformed reading habits often mean that I’m not aware of the latest developments in our nation’s dismal political drama. When people ask me if I’ve seen the news about Trump’s Russia ties, or impeachment votes, or the latest neo-Nazi rally, I have to admit my ignorance. At first, this state of being recessed made me feel like a bad citizen. When friends chided me for shirking my responsibilities, I meekly accepted their criticism. But now I feel like I see things more fully from my isolated perch; I feel ready to re-enter the world with a sense of perspective and priority.

More from A Year in Reading 2017

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005