Here are eight notable books of poetry publishing in December.

Witch Wife by Kiki Petrosino

Witch Wife by Kiki Petrosino

“Who shall change my vile body into a glorious body / when I know there’s glory at the end of my prayer?” The first quarter of Witch Wife is bound by bodies: bodies plagued, bodies unsettled. “For this glob of a girl who feeds like a grub,” Petrosino writes, her consonants bubbling like the incantations suggested by her title. “Poor poorless receptacle for Presidential-fitness-test-sweat, poor pudding poured into too few pans.” The anxiety of the book’s first quarter turns and evolves into something like mist in the second quarter of the book, in poems like “Europe”: “I’ll never be so lonely again, or young enough / to weep in my clothes on the street.” Witch Wife offers that maybe all love stories are stories of bodies. We are within before we are without. Petrosino is a unique voice, churning a mixture of smirk and mirth: “My exes shall rise up from their Mazdas / & adorn themselves in denim.” Anne Sexton haunts the third quarter of this book: “Some ghosts are my mothers / neither angry nor kind / their hair blooming from silk kerchiefs.” Witch Wife is a weird wonder, something altogether new in its combinations. From the title poem: “Your gloves are green // & transparent like the skin of Christ / when He returned, filmed over with moss roses— / I’ll conjure as perfect an Easter.” The book’s final quarter shakes like the end of a folk tale, the other world and this world coming together: “It happens at my desk: a gathering in. As if the room were a forehead graying at the lid.” The sky collapsing; “Something happens but it doesn’t keep happening. This is a careful time.” We should believe it.

Bullets into Bells: Poets and Citizens Respond to Gun Violence edited by Brian Clements, Alexandra Teague, and Dean Rader

Bullets into Bells: Poets and Citizens Respond to Gun Violence edited by Brian Clements, Alexandra Teague, and Dean Rader

“Everything at the end of a bullet’s journey becomes conjecture,” writes Colum McCann in the introduction to this painfully appropriate collection. The bleak reality that McCann describes is all the more reason for a book whose conviction, he writes, “is that we should be in the habit of hoping and speaking out in favor of that hope.” “The long night begins,” ends a poem by Jimmy Santiago Baca. “Seasons matter little to him,” writes Kyle Dargan of a Virginia farmer who sells a gun to the “tremulous hand” of a boy: “none of the guns he sells are grown from seed.” Ross Gay stirs me awake with lines I can’t forget: “The bullet, in its hunger, craves the womb / of the body. The warm thrum there. Begs always / release from the chilly, dumb chamber.” Bullets into Bells believes in conversation over false conversion, and in that spirit, includes responses to each poem—a unique, and often moving, element of the book. After Reginald Dwayne Betts’s poem “When I Think of Tamir Rice While Driving”—in which he laments “this should not be the brick and mortar / of poetry, the moment when a black father drives / his black sons to school”—Tamir’s mother responds: “When I lost Tamir, I lost a piece of myself.” Poetry won’t make us whole again, but we need a form for our shouts and our cries. Follow Natasha Trethewey here: “And how could I not—bathed in the light / of her wound—find my calling there?

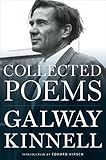

Collected Poems of Galway Kinnell

Collected Poems of Galway Kinnell

“Jesus, it is a disappointing shed / Where they hang your picture / And drink juice, and conjure / Your person into inferior bread— / I would speak of injustice, / I would not go again into that place.” Kinnell “sacramentalized experience,” Edward Hirsch says, alluding to how the poet’s youthful Catholicism became both a source of tension and nostalgia. His long poem from 1960, “The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World,” captures that synthesis. A beautiful, comprehensive, playful snapshot of the city: people, buildings, objects illuminated fresh: “In the pushcart market, on Sunday, / A crate of lemons discharges light like a battery.” Kinnell’s Collected also includes The Book of Nightmares, a book of quotable lamentations: “Let our scars fall in love.” There’s a considered gentleness to Kinnell’s verse, as in “Goodbye,” for when “My mother, poor woman, lies tonight / in her last bed. It’s snowing, for her, in her darkness.” By the time the poem ends, like with so many of Kinnell’s tales, we have been carried, and are placed, gently, somewhere else: “It is written in our hearts, the emptiness is all. / That is how we have learned, the embrace is all.”

Let’s Not Live on Earth by Sarah Blake

Let’s Not Live on Earth by Sarah Blake

“You will lose your body to // sadness at a point / like a temperature // and then you will wake and wake / and wake and wake and wake to it.” Melancholy, by nature of its blurred edges and ambiguous heartbeats, is so difficult to capture with poetic precision. Blake gets close to that pained place through her recursive lines, her willingness to linger on moments. “I know people are judging me as a mother all the time,” she writes in a single line, like an exhale of the inevitable. Yet there’s a strength here, and it is often delivered with the humor that comes from frustration. In one poem, after the narrator is almost denied coverage for anxiety medication, she walks her son home in a stroller. It has gotten very warm, and once home, covered in sweat, she thinks what a relief it will be to simply sleep that night. To make it through life, and be given that small grace: “You might call it escapism but this is / how life works, trying to pull / us free, creating the break that we might // split ourselves upon.”

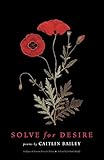

Solve for Desire by Caitlin Bailey

Solve for Desire by Caitlin Bailey

Grete and Georg Trakl, sister and brother, pianist and poet, are given new life in Bailey’s debut collection. Plagued by addiction, scarred by war, driven to suicide, both are frozen in history, but Bailey offers Grete her voice. The siblings hold a connection beyond even love, some region possibly only accessible through poetry. “The most brilliant part of you exists to haunt me,” she writes. “Sometimes I can’t believe my heart, // how it continues. How it isn’t black and withered.” Bailey often delivers short poems like flashes; those can be held in your palm, however mysterious: “If a horse is allowed / to graze freely after a winter / in the barn / it becomes sick with pleasure.” Other lines, like “I am hostage to your absence,” bleed across the rest of poems, heavy in their chorus. Although Bailey is creating a fictional vision of two hearts, her words rest in that curious space between abstraction and touch, so this is a book to place upon one’s soul.

Let’s All Die Happy by Erin Adair-Hodges

Let’s All Die Happy by Erin Adair-Hodges

In “Ode to My Dishwasher,” the narrator sighs: “It is late, my love, and you are loud / worrying at your work.” “To be a grown woman,” she thinks, “alone / and unclean is a powerful thing.” She thinks of her mother, who “had so many rubber gloves / I was surprised by the sight of her hands // which seemed to me old / even when she was young.” The narrator’s mother is a familiar refrain in Let’s All Die Happy, a book sustained by Adair-Hodges’s often darkly-comic voice. Lament is one of her main modes. She doesn’t quite look back in anger, but there’s a skepticism about the past. Like those years she “thought I loved God and His son,” which might have been because she “liked being good // at Church, A-pluses in verses, hymns.” “I loved Him,” she reflects, “like a savings account, feeling holy // in my asceticism but waiting for the day / I could go to the Bank of Eternal Good Things.” So often in these poems the narrator ends up alone, misunderstood, separated—after she’s opened her heart. In “The Trap,” she knows “There is no greater tragedy than to be young / and think you know what joy will look like / and so clunk and pigeon / through corridors and malls, flapping against the linoleum / of heartbreak.” A sweet book for hearts gone sour, Adair-Hodges skillfully moves between varying songs, and the book’s key lies in a single phrase: “I am graceless but I am not depraved.”

The Complete Poems of A.R. Ammons: Volume 1 and Volume 2

The Complete Poems of A.R. Ammons: Volume 1 and Volume 2

From his 1955 self-published debut Ommateum with Doxology to the posthumous 2005 collection Bosh and Flapdoodle, these two volumes offer 966 poems from a poet whose complexities and personal labyrinths we have yet to fully understand. In her introduction, Helen Vendler alludes to a forthcoming biography, but for now, we have the poems. He began writing them while in the Navy. He continued writing while he was a scientific glassware salesman. His words hold an oddity and sublimity that sets him apart from even his experimental peers. In “Easter Morning,” on the tragic death of his younger brother: “I have a life that did not become, / that turned aside and stopped, / astonished: / I hold it in me like a pregnancy.” His brother’s young death paused his growth, and he’s remained chained to that moment where he can only “yell as far as I can, I cannot leave this place.” Ammons is like some wild radical lover of language in old clothes; his tightly columnar poems are both playful and traditional. Timeless, probably. Often tongue-tied to truth: “Old men drain and dread and dream and dress / and dribble and drift and drink and drip and // drone and drool and droop and drop and drown / and drowse, dry, and dry up.” I love “Soaker”: “You can appreciate / this kind of rain, / thunderless, / small-gauged / after a dry spell, / the wind quiet, / multitudes of leaves / as if yelling / the smallest thanks.” I have never read a poet who brings me so close to infinity, where we are equally in awe and terribly afraid.